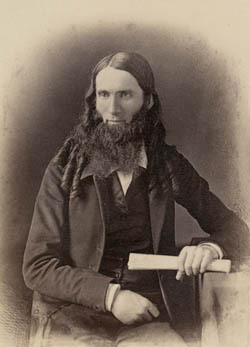

Charles Calistus Burleigh: An Unkempt but Powerful Force for Abolition

Charles Calistus Burleigh Basics

b. November 3, 1810, Plainfield, Connecticut

d. June 13, 1878, Northampton, Massachusetts

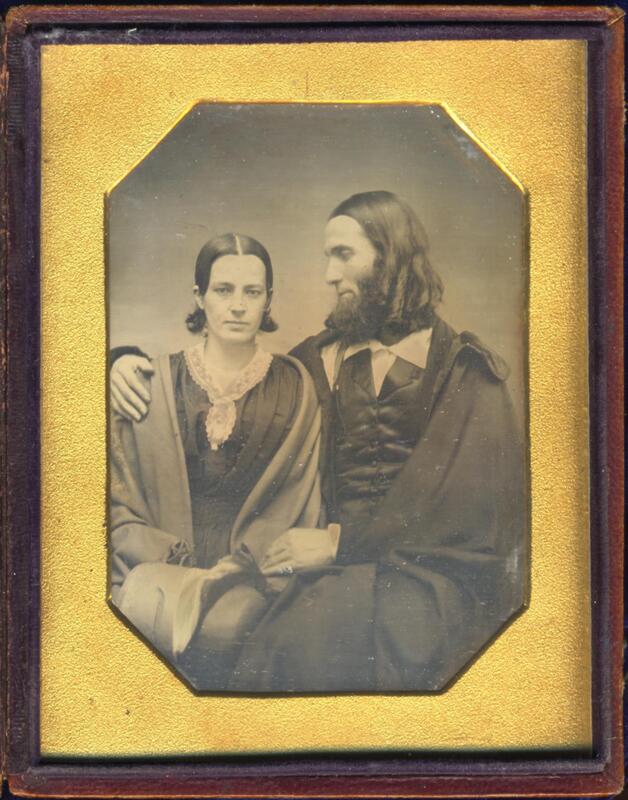

m. Gertrude Kimber (1816-1869), October 24, 1842, Kimberton, Pennsylvania

lived in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Vermont at various points in his life

I. Overview of a Remarkable Life

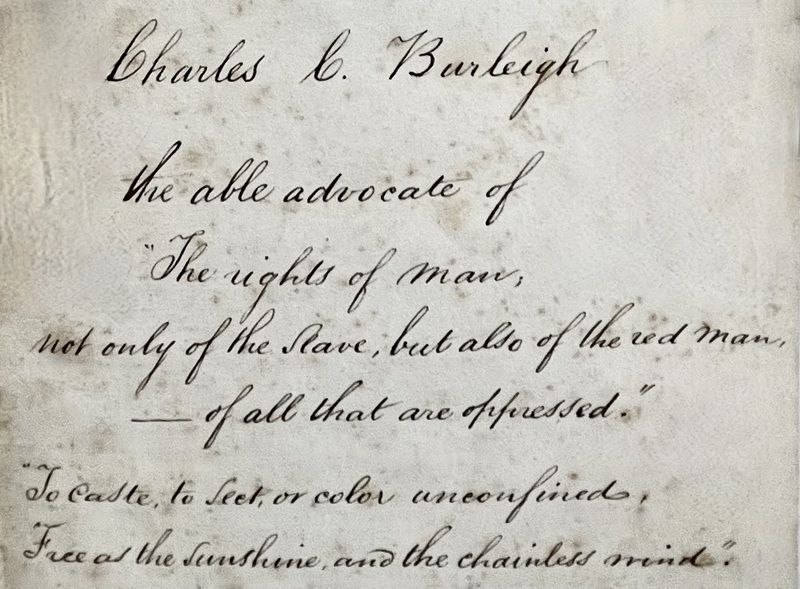

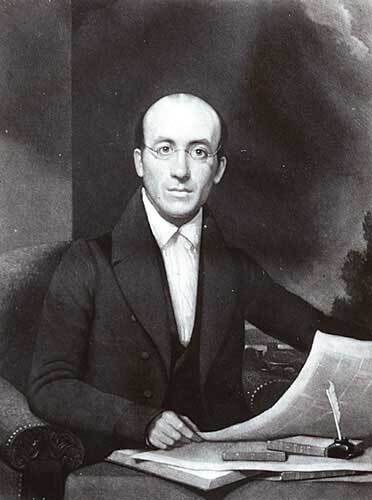

Charles Calistus Burleigh deserves a book-length study. His forty-five years of activity in Reform touched on every corner of the Benevolent Empire. His writings are strongly argued, reflecting his training in law, but his renown came from his powers as an orator and editor. He made substantial contributions to the Abolitionist movement in four different states - Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, and Pennsylvania - with speaking tours taking him to many more.

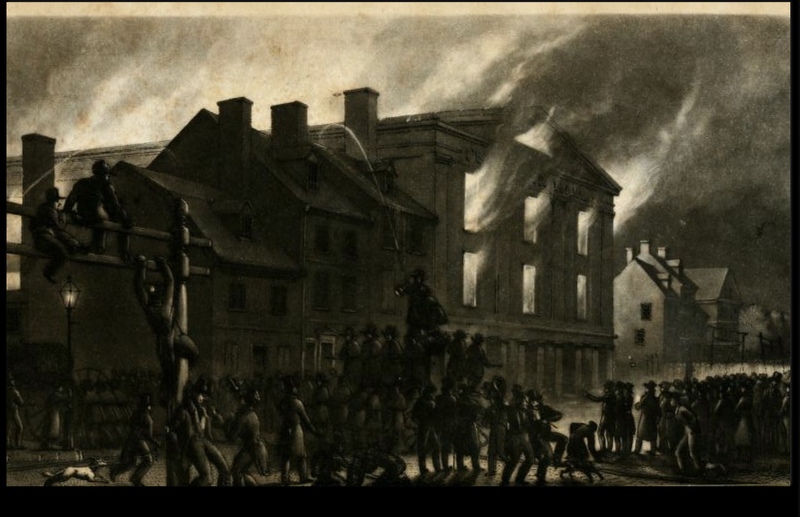

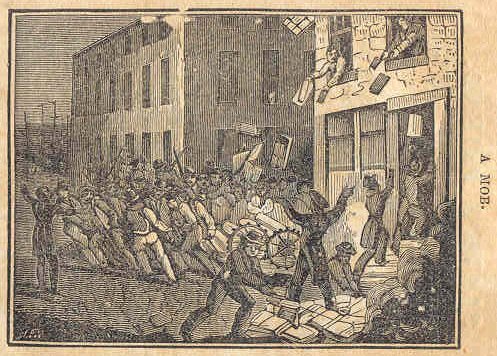

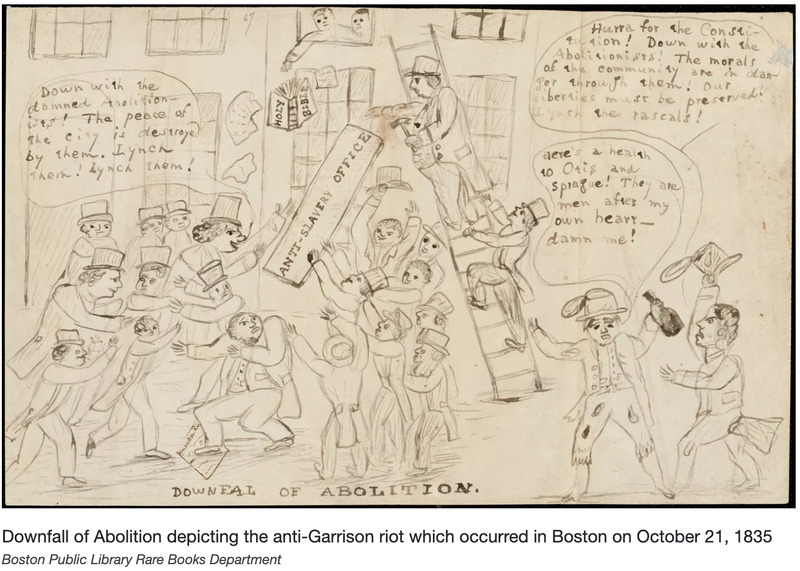

His principles of non-violence and non-resistance were dramatically tested, seemingly every year. He was present at such famous incidents of violence as the ending of the Canterbury Female Academy, the mobbing of William Lloyd Garrison, and the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall. Indeed, his every scheduled appearance carried the possibility of rotten eggs and threats of bodily harm.

His support of women's rights was well ahead of most men, in both practical and philosophic terms. His marriage to Gertrude Kimber was a true love match, and his respect for women activist/thinkers like Lucretia Mott and Abby Kelley Foster comes through in his reports on their orations. His ability to work cooperatively with his African-American colleagues, in particular Robert Purvis, Charles Remond, and Stephen Gloucester, will be recounted in detail on this website.

A tentative division of the periods of Charles Calistus Burleigh's life is presented here, subject to further research and refinement:

1810-1831 - youth, education, farming and commencing his study of law, all in Plainfield, Connecticut area

1831-1832 - studying law in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and getting first taste of editing with Anti-Masonic newspaper We the People

1833-1834 - major involvement in Canterbury Academy for Black Women, run by Prudence Crandall; he edited The Unionist in Brooklyn, CT

1835-1837 - Based in Massachusetts, worked with William Lloyd Garrison & assisted in editing The Liberator; became an Anti-Slavery Agent

1837-1842 - Philadelphia - assisting Benjamin Lundy, travel to Haiti, Pennsylvania Hall, editing The Pennsylvania Freeman, courting Gertrude Kimber

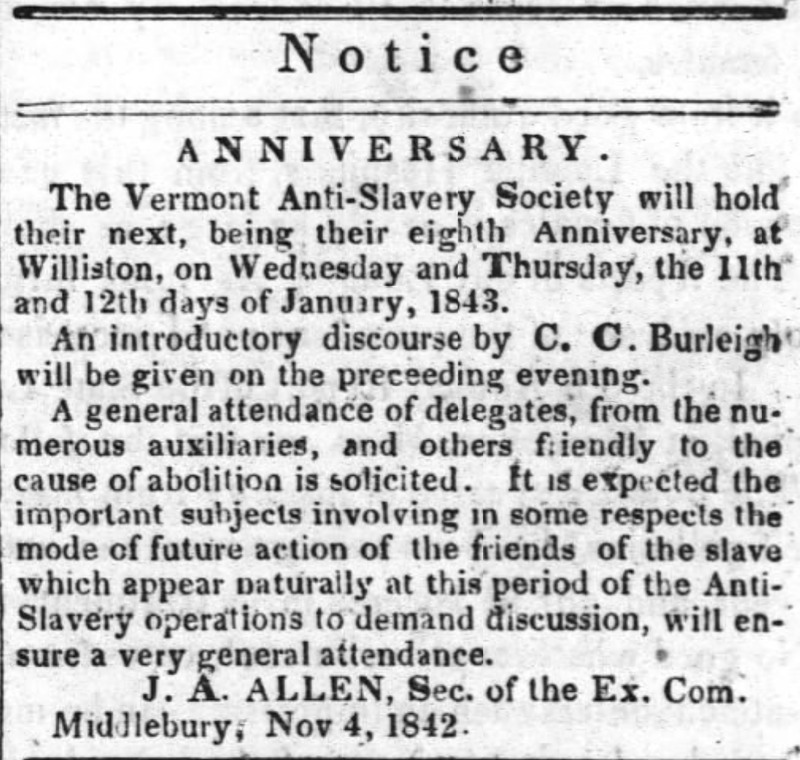

1842-1843 - Marriage and Vermont - wedded Gertrude Kimber, and took a one-year stint editing an anti-slavery paper in Vermont

1843-1856 - Philadelphia - helping edit The Pennsylvania Freeman, anti-slavery lecturing and leadership

1856-1861 - Return to Plainfield - helping with elder care and farm, as well as continuing anti-slavery activism

1861-1873 - Northampton, Massachusetts - leading Free Congregational Association, continued anti-slavery activism, involvement in Woman's Rights and Black suffrage; death of Gertrude (1869)

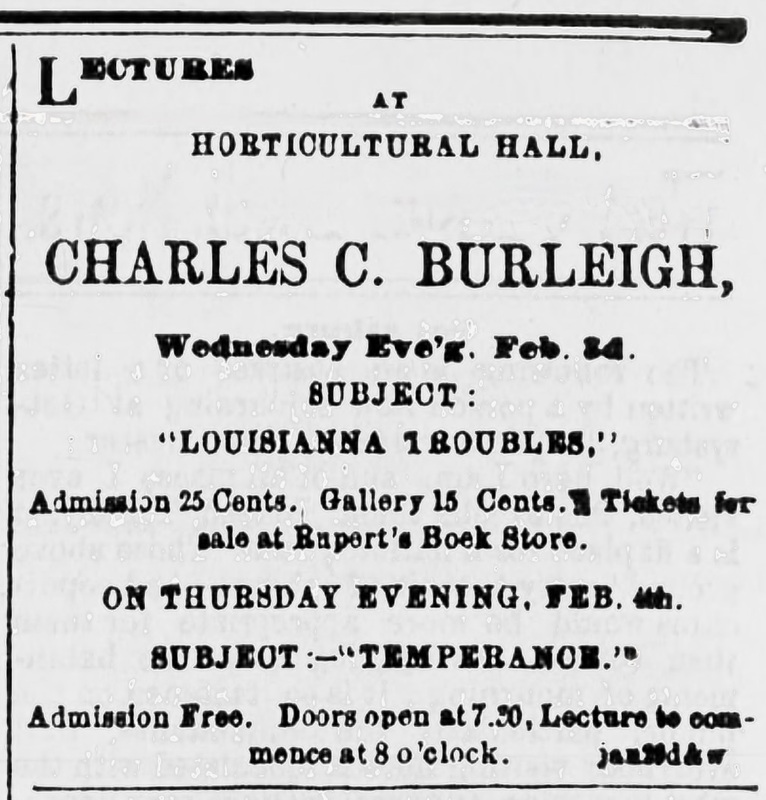

1873-1874 - Leaves the Free Congregational Church in Bloomington, Illinois, but continued Woman's Rights and Temperance work elsewhere

1874-1878 - Back in Northampton; still traveling and lecturing. Spent considerable time in eastern Pennsylvania, stumping for the Prohibitionist ticket in that state, in 1875.

His 1878 death occurred when he was hit by a train; he lingered for a few days until the injuries proved fatal.

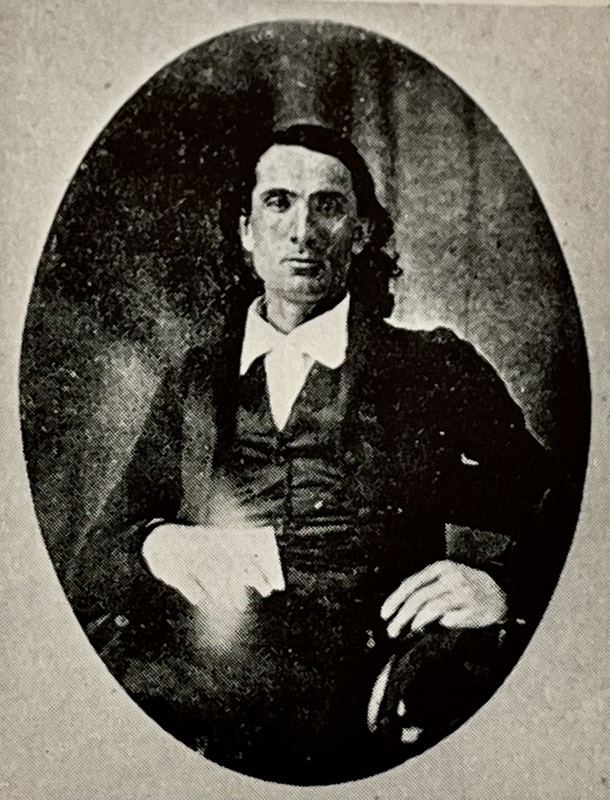

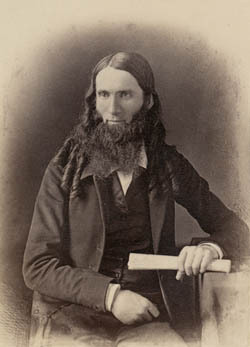

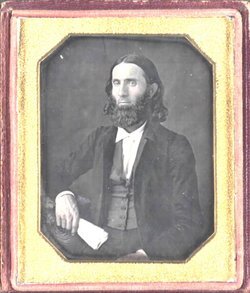

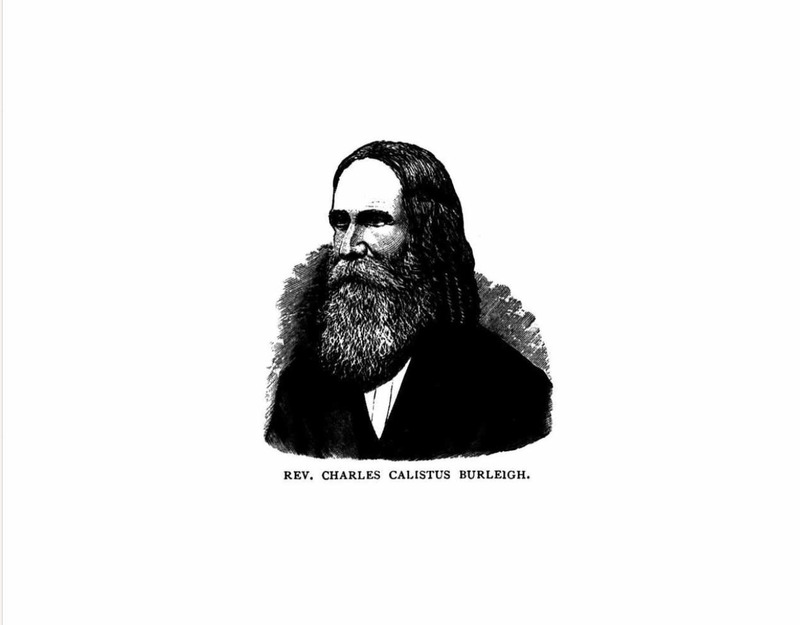

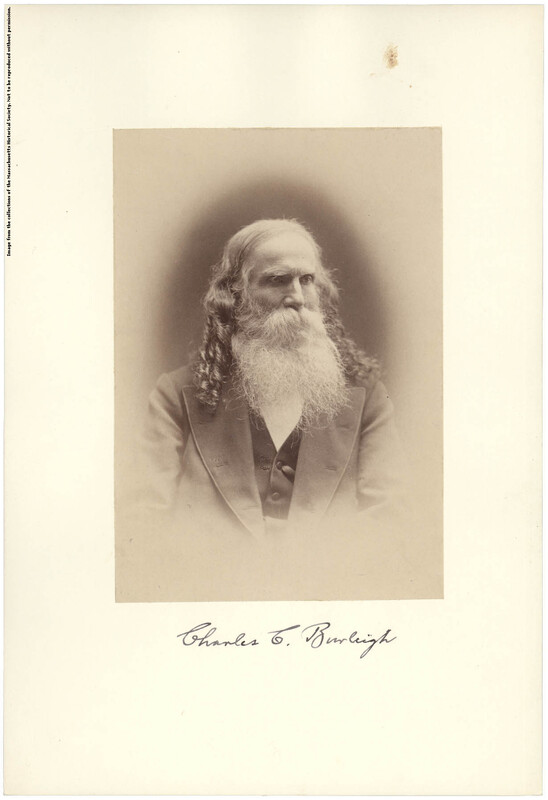

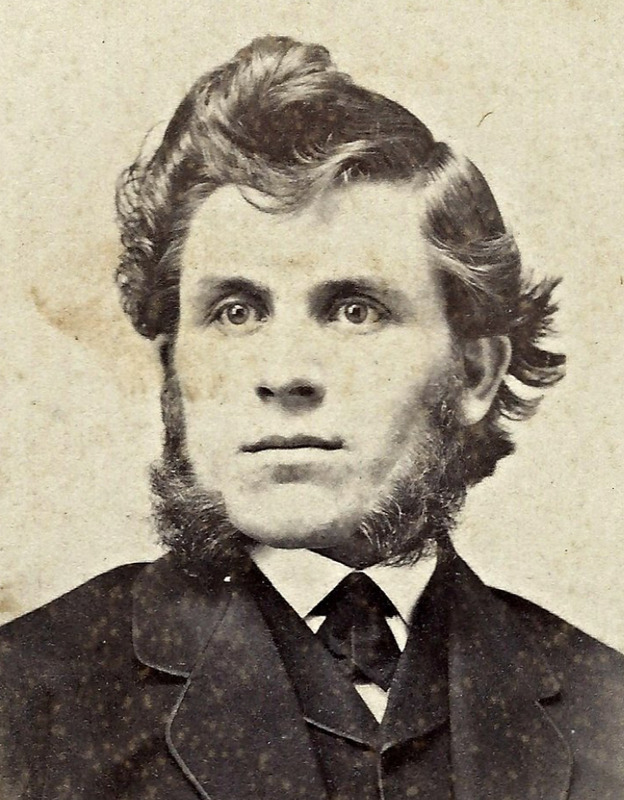

II. The Notable Appearance of Charles Calistus Burleigh

He wore his hair long, with ringlets in it. His clothes were often disheveled. He wore a beard regardless of the fashion of the day. And both friends and enemies commented constantly on his appearance, tsk-tsk-ing him for his oddities.

Here is one example of how is appearance was handled by the press:

Charles C. Burleigh, of the family of natural poets and orators, arose, his long flowing sandy beard and hair, and plain attire giving him a very unfashionable appearance and causing people unacquainted with him to open their mouths and eyes in ridicule and astonishment, but when he opened his mouth they generally closed theirs, for he is a most eloquent and logical speaker, and most perfectly at home on the question of non-resistance. For about half an hour he poured forth a torrent of eloquence and logic, which, in theory, looked most beautiful and sublime, but through all this beauty there was a feeling pervading the audience that this perverse generation was not perfect, angelic, and holy enough to carry on a principle which evidently belongs so far down in the unmeasured and unmeasurable distance of "the good time coming."

An opponent of Immediate Abolition, writing in the Cincinnati Times in April 1852, described how Charles Burleigh:

with locks like Absalom, and a beard that would awake the envy of a buried patriarch, spoke in a voice rendered husky by too much hallooing and singing of Anti-Slavery anthems. He is a fanatic by nature, and an abolitionist by trade and occupation, with all of Douglass' exaggeration of sentiment, and without its mitigating reason, in causes personal to himself.

We at the Burleigh project have a file on this issue, and will soon digest, annotate, and upload it. But for now, these two quotes say all you need to know:

FINISH UP THE WORK.—At an early stage of the anti-Slavery agitation, sundry of those more prominent on the Abolition platform concurred in leaving their hair and beards to grow as nature dictated. In due season, one of these—(Charles C. Burleigh,)—was waited on by a committee or remonstrance against this invocation of new prejudice and odium upon the already overladen cause. He heard the remonstrants patiently to the end, and then announced that he should not abate one hair. “For,” said he, “I have devoted my future efforts to the over-throw and extinction of all Slavery; and, if I am to be controlled by others’ tastes inn the matter of my own hair and beard there will be at least one slave left, though all the negroes on earth should be freed; and I cannot work for aught less than complete and universal freedom.”

This piece may seem quaint and amusing, but there is an emphasis on bodily autonomy that speaks to our own age - as well as to the universality of Charles C. Burleigh's understanding of freedom.

The most important assessment of any one's appearance, though, should come from their spouse, and Gertrude's opinion silences all other complainers when she says that Charles:

is the best man that ever was, & spite of what Old Mr. Stowe says, as reported in Harper, is so good looking that my modesty will not permit me to tell all I think about that!

References

“Finish up the Work,” The Recorder (Greenfield, Massachusetts), March 1, 1869, p. 1

Gertrude Kimber Burleigh, letter to Samuel May Jr., November 14, 1857 - online from the Boston Public Library Abolitionist collections"

"Non-Resistance," The Providence Mirror, quoted in Frederick Douglass' Paper, November 20, 1851

"Spirit of the Press in Regard to the Cincinnati Convention," Frederick Douglass' Paper, May 13, 1852 - an extensive reprint from the Cincinnati

III. Charles Calistus Burleigh in the 1830s: Canterbury, Boston, Philadelphia, Haiti & New York City

John Jay Chapman wrote of Charles C. Burleigh that he "was turned from the career of a brilliant advocate and was transformed for life into an evangelist of liberty, through the courage" of Prudence Crandall.

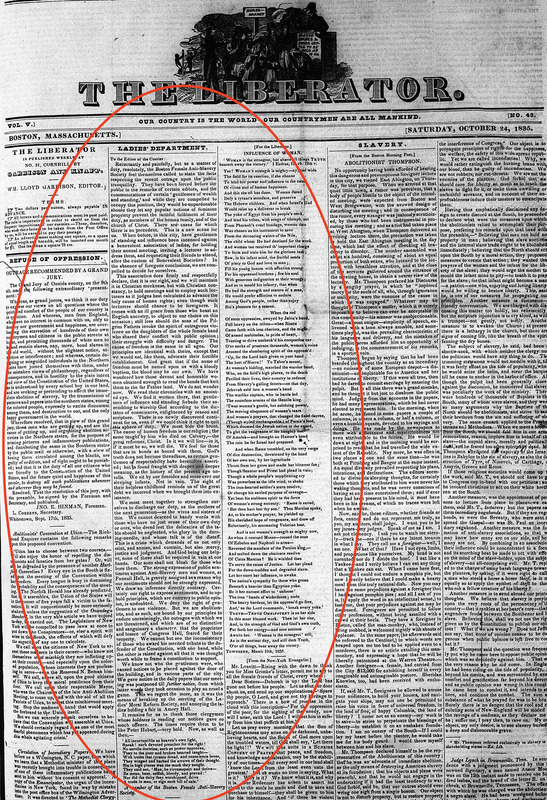

After the closing of the Canterbury Academy, Burleigh moved to Boston, where he was assisting Garrison in publishing The Liberator. His retelling of the murderous attempt to take Garrison by mob violence in October of 1835, is trusted by historians and was applauded by Garrison himself for its accuracy.

References

John Jay Chapman, William Lloyd Garrison. Second Editon. Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1921.

This is the entire Liberator story on the mobbing of Garrison. Charles C. Burleigh prefaces it with an article from the Boston Daily Advocate, leading to the misleading headline.

Charles Calistus Burleigh, "Another Argument for Sir Robert Peel" and [account of the mobbing of William Lloyd Garrison]. The Liberator October 24, 1835 5:43:171

[From the Boston Daily Advocate, of Thursday.]

ANOTHER ARGUMENT FOR SIR ROBERT PEEL.

In his speech, at the Tamworth dinner, Sir Robert Peel attempted to show that a Republican Government would never do for England, by reading from American papers accounts of riots. Boston, we are ashamed to say, has helped the Tory Orator to another argument/ The incendiary Gazette, has finally succeeded in getting together spectators to see a mob, and thus made a mob. Some ladies wanted to have a meeting yesterday afternoon, about a Slavery Society, at their own rooms, No. 46,Washington-Street. It might have been in bad taste for ladies to be ambitious of martyrdom, but as to that they had a right to do as they pleased, for they violated no law, and though our fathers were given to making war on their oppressors, it was never thought that a mob could ever be got up in Boston to attack women. Nevertheless, an infamous handbill was stuck up round the town calling upon every body to go to the Abolition Rooms and snake Thompson out, and punish him. If the authors or bill-stickers of that incendiary handbill can be found, they ought to be indicted. We saw one of the vile things torn down with indignation, by a revolutionary soldier. Such things, and he, are a disgrace to Boston. Every honest man should tear them down. He was no abolitionist neither. The spectators, perhaps a thousand, collected in the afternoon, in Washington-Street, looking for a riot; the surest way in the world to make one.

Many people went to the Antislavery office, but there was no meeting there, and the Mayor informed the “sovereigns” that George Thompson was not in the city, and that the ladies had concluded to disappoint the gentlemen of their anticipated glorious triumph over twenty females, by not holding any meeting at all. THereupon the Antislavery sign was taken down and demolished, and Mr. Ely, Editor of Zion’s Herald, was hustled in a rough manner. Mr. Garrison, after escaping from the rooms by a back window was followed by the “sovereigns” who seized him, and, it is said, but we trust falsely, a rope was put about his neck. Mr. G. was rescued and carried by his friends to City Hall, from which he was conveyed in a hack, accompanied by the Mayor, and deposited in the jail for safe keeping—a new receipt for preserving the liberty of the subject, about which our fathers used to have some very silly notions, when they spilt their blood on Bunker Hill! The whole of this was the work of a very few, and the mob was made up of idle spectators. If the well disposed would stay at home on such occasions, there would be no mobs. The South will probably be pacified now, and wait patiently to see the good people of Boston hang all the Abolitionists. Sir Robert Peel and the British tories will be delighted when they get hold of this proof of the “Supremacy of the Law” on the city of Boston. It was expected that the Gazette office would have been illuminated, in honor of the triumph over the women.

§§§

The above is the Daily Advocate’s account of the tumultuous proceedings of Wednesday afternoon. Though nearer the truth than any other which I have seen in the daily papers, it is in some particulars inaccurate. Having been an eye-witness to almost the whole affair, having occupied a position favorable for observation, I will endeavor to give a correct statement of what I saw and heard.

It seems that the notice of a meeting of the Female Anti-Slavery Society, to be holden in the Anti-Slavery Hall, excited the special indignation of certain of the corps editorial, whose wrath was no way abated by the suspicion—purely gratuitous—that Mr. Thompson was to address the meeting. THe indications of an approaching disturbance were such as to induce the Ladies to apply to the Mayor, and require the protection of the civil authorities, if the occasion should render it necessary. The city government sent to the Anti-Slavery Office to ascertain whether Mr. Thompson would be present, thinking that if the people, in case of their assembling, could be assured that he was not and would not be at the hall, they would quietly disperse. The assurance was given, that Thompson not only would not be at the meeting, but that he was not and would not be even in the city.

About 2 P. M. I went to the office in company with Mr. Garrison, and at that early hour a number of young men had collected about the door of the hall, and a few ladies were seated within. Mr. Garrison entered the hall, and after remaining a short time, came to the door, and addressing the crowd without—now increased so as to fill the entry—requested them to withdraw, as the meeting was exclusively for ladies. They paid no attention to the request, and soon after Mr. G. left the hall and went into the office, where he remained quietly—most of the time writing—till after the police had cleared the entry and staircase. At one time a rush was made at the office door, (which was locked) and some one kicked against it and smashed in the lower panel. Except the destruction of the sign, this was the only damage done to the premises, so that the story, which had found its way to some of the papers, that the books and papers of the Society were destroyed, is utterly false. Not a leaf of a single tract, not a scrap of a single paper was destroyed or even touched by the mob, nor did a single individual of the mob enter the office, unless those who went in to take down the sign, ostensibly, and for aught I know, really by the Mayor’s orders, were a part of the mob, which I presume none will say was the case.

But to return. The ladies had continued to arrive, and were permitted to pass through the constantly increasing crowd, not, however, without having their ears frequently saluted with insulting sounds, and one or two of the colored ladies were rudely pushed into the hall.

The exercises of the meeting were commenced by reading an appropriate passage of scripture, which was followed by prayer. The voice of the reader and leader in prayer, was clear, calm and firm; not the slightest tremor was perceptible, or any indication that she felt the least fear or agitation. Once during the prayer, a piece of board five or six feet in length, was thrown over the temporary partition which separates the hall from the entry, but fortunately did not fall upon any of those within. At another time the crowd made a rush against the partition, supposedly with the dodge of breaking it down, but desisted after starting one end of it from its place. A peace officer, at the request of a gentleman friendly to the meeting, had stationed himself near the door, but his efforts to persuade the mob to disperse were unavailing. At length the mayor arrived, with several officers, and repeatedly called on the crowd to retire, but with no better success, though he assured them that Thompson was not in the city. He then requested the ladies to leave the hall, supposing, probably, that when they were gone, the mob would be satisfied, and disperse. The ladies, who had proceeded so far as to have commenced the reading of their annual Report, adjourned, and withdrawing to a privat house, proceeded with their business, electing their officers for the ensuing year, &c. Meanwhile, the mob, after pausing awhile, and venting, ‘in curses not loud but deep, their rage at being disappointed of their expected prey—Thompson—began to vociferate for the sign of the Anti-Slavery Office. Two or three persons—some of them, if not all, belonging to the police—entered the hall, avowing their intention to take down the sign, and saying that such were the mayor’s orders. They soon effected their purpose, and the sign was lowered from one to another, till it reached the pavement, and then—what a rush! There seemed to be a furious emulation to be foremost in tramping upon the luckless board, and rendering it to splinters. It was covered instantly with stamping feet, and a company of Japanese, trampling the cross, could not have enacted their part with more fiery zeal than was displayed by as many of the ‘respectable citizens’ (vide Commercial Gazette,) of Boston as could get at the object of their fury. Almost instantly, fragments of the board were seen brandished about in the crowd, and then were subjected again to the refining process, and reduced to more chips. Every one seemed anxious to get a piece, and the design appeared to be, to make as many pieces as possible, that every one if possible, might be gratified. Whether they supposed a bit of the wicked Abolition board would serve as a sort of talisman against the influence of ‘Garrisonism,’ and ‘Thompsonism,’ and ‘Mayism,’ and all the other terrible isms of these dreadful ‘incendiary fanatics,’ or whether they merely wished to preserve a trophy of their glorious achievements, against a handful of ladies and their place of assembling, is a point which I leave undetermined. After all, however, they did not monopolize the chips, but that is neither here nor there.

After the ladies withdrew, the police found but little difficulty in clearing the entry and stair-case. The Mayor now expressed his anxiety to get Garrison out of the building, for it was evident the mob were determined not to disperse till he was either in their power or unquestionably beyond it, and it was thought important that they should be dispersed before dark. Till this time Garrison had been seated in the office, manifesting no sign of alarm, either in deed, word, or look, and now, when he came out to the entry, he appeared as he had done through the whole tumult, calm, collected and cheerful. I could perceive not the least change in his manners from that which he exhibits in the entire absence of danger, or of even the remotest apprehension of danger. Some of his friends, united with the Mayor and officers, in endeavoring to find a way of escape from the building, in which they at length succeeded. He complied with their request, and retreated from the window, in the rear of the building, after which one of the sheriffs announced to the populace that he had made diligent search for Wm. Lloyd Garrison but that he could not be found. The dense crowd now began rapidly to grow thinner, and soon the street was almost wholly cleared. This I at first supposed was caused by the people’s returning to their homes, but it was not long before I discovered my mistake. They were in chase of Garrison, having been informed by some spy or looker out, that he had escaped from a back window. Going to the post office, I saw the crowd pouring out from Wilson’s Lane into State St. with a deal of clamor and shouting, and heard the exulting cry, ‘They’ve got him—They’ve got him.’ And so, sure enough, they had. The tide set toward the south door of the City Hall, and in a few minutes I saw Garrison between two men who hed him and led him along, while the throwing pressed on every side, as if eager to devour him alive. His head was bare, his face a little more highly colored than in his most tranquil moments, as if flushed by moderate exercise, and his countenance composed. I have been informed that when seized he uttered not a word, nor raised a hand for his defence, but yielded unresistingly, in perfect accordance with his well known principles. He had been concealed in a carpenter’s shop, as the story goes, and was betrayed by an apprentice who worked there. Some say the apprentice was an Irish boy, but as that would look somewhat like ‘foreign interference,’ which the patriotic citizens of Boston are known not to tolerate, I conclude that story must be set down as apocryphal.

As Garrison came opposite the City Hall, the Mayor and peace officers, with the aid of some in the crowd, who, if not Garrison’s friends, were at least unwilling that his blood should be shed in the streets of Boston, succeeded in rescuing him and bringing him to the Mayor’s office. BEyond this I cannot testify as an eye-witness, for I returned to the office assured that Garrison was safe. He remained under the Mayor’s protection, till a carriage was procured, in which he was placed and conveyed to the prison in Leverett-street, where he was lodged for safe keeping. As a mere matter of form, a warrant was made out against him, as a disturber of the peace, he was committed and remained in jail over night, and was arraigned and of course discharged in the morning, and by request of the Mayor, immediately left the city. Several of his friends saw him while in the prison, and all agree that he was not in the least disheartened or cast down. ‘Never,’ says one f them, ‘never have I seen him in better spirits.’

A story is in circulation, and I am told that some of the dailies are giving it currency, that his agitation was so great as to unsettle his mind, and that he is actually deranged. The over-officious authors and circulators of this report, may make themselves quite easy on Mr. Garrison’s account. They may rely on it he is not half as crazy now, with all the cause for agitation which he has had, as some of the, so called, respectable citizens of Boston. I saw much more that looked like the ravings of insanity among the besiegers of the Anti-Slavery Office, and the disturbers of the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery meeting, I venture to say, than any man ever saw in Garrison and all other Abolitionists from Maine to Georgia. The mental derangement is all on the side of the mob party, in this instance, as, I believe, in every other.

I make no comment, on the conduct of the ‘well-dressed’ mob, for comment, if not needless, is at least not required at my hands now. Indeed, I have not told all the facts which deserve to be recorded. Some of these may appear yet.

The Abolitionists, so far as I could observe, and I believe generally, remained true to their principle, of rather suffering wrong than doing wrong. Not one raised his hand to repel violence by violence, though they were sufficiently numerous and possessed enough of physical power to have wreaked bloody vengeance upon their injurers had they acted on the common principles of retaliation. But they do not, and I trust never will, act on those principles. They have a higher and a better standard of morality—the peaceful principles of the gospel. Their forbearance was not owing to a want of courage. There were men among them—yes, many men—ready to lay down their lives, had duty required the sacrifice. Nothing which looked like fear could be discovered in their conduct or their language. But it is unnecessary to say that those men are not cowards, who fearlessly pursue the path of duty, in the midst of such threats and abuse and demonstrations of violence, as are visited upon the Abolitionists at the present day. If ever men encountered peril, the Abolitionists surely have encountered it in abundance. If ever men have manifested courage—the best of courage—that which opposes meek endurance, but unflinching perseverance, to brutal outrage—the Abolitionists have manifested such courage. Can such men be crushed? Wait the event and see.

C. C. BURLEIGH

__

- It is true that two or three books were thrown to the mob but they were not Anti-Slavery books, nor taken from the Anti-Slavery Office. The Hall of the Anti-Slavery Society is also occupied as the Episcopal Missionary Chapel, and several prayer books were lying on the seats, when a part of the mob rushed in, immediately after the ladies left the Hall. The ‘patriotic citizens,’ in the ardor of their patriotic zeal, seized what first came to hand—the prayer books–and wither from sheer wantonness, or because they thought that being in the Anti-Slavery Hall, they must of course be Abolition books, and in their eagerness to display their patriotism, forgetting to stop and examine they hurled them down among the rabble of gentlemen below. Or, perhaps, they thought the prayer book–especially as it contains extracts from the Bible–is on the whole about as incendiary as the Abolition tracts themselves. If so, they judged aright. Whether they acted right, is another question. C.C.B.

IV. Charles Calistus Burleigh in the 1840s: Schism, Romance, and the Struggle for Universal Freedom

The schism of the Abolitionist movement in 1840 was traumatic, and led to destructive horizontal rhetoric among Abolitionists who were turning against each other - patterns all too typical of the history of progressive movements. While, in retrospect, we can see that attacking slavery along separate moral and political lines was likely beneficial to the ultimate success of that movement, it didn't feel that way to the participants. Charles C. Burleigh was a key figure in the schismatic struggles, present at many of the key meetings that led to the "Old" and "New" organizations (American Anti-Slavery Society, and American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, respectively).

While there is much more research needed to determine precisely where Charles C. Burleigh stood at the key moment in 1840, it seems that he wanted to avoid a schism, by suggesting that the AA-SS could hold both political abolitionists and moral suasion abolitionists, but that the organization as an organization would not undertake political work or endorse candidates. However, once the schism occurred, Charles was, and always remained, a staunch Garrisonian moral suasionist.

But not everyone in the Burleigh family was in the same camp. Charles and William, the two most prominent Burleigh family siblings at the time, stood firmly in opposite camps, with William embracing political Abolition. There are hints though, that the two brothers still respected each other - they advertised each others' books in their respective papers, and William's poetry volume was given as a gift from Charles and Gertrude Burleigh to a friend of theirs.

V. Charles Calistus Burleigh in the 1850s: The Growing Crisis, Loss and Return to Plainfield

Death of mother, return to Plainfield in the latter years of the decade

VI. The 1860s - War and Peace, A New Spiritual Vision, Gertrude's Death

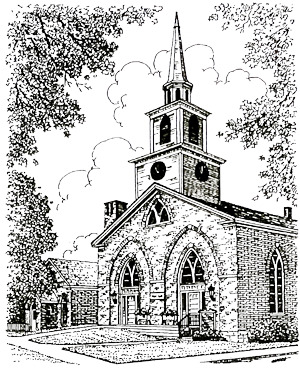

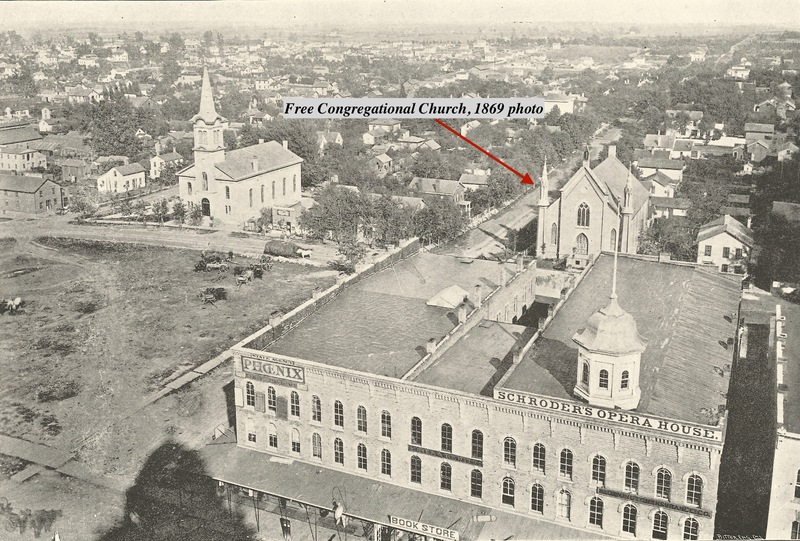

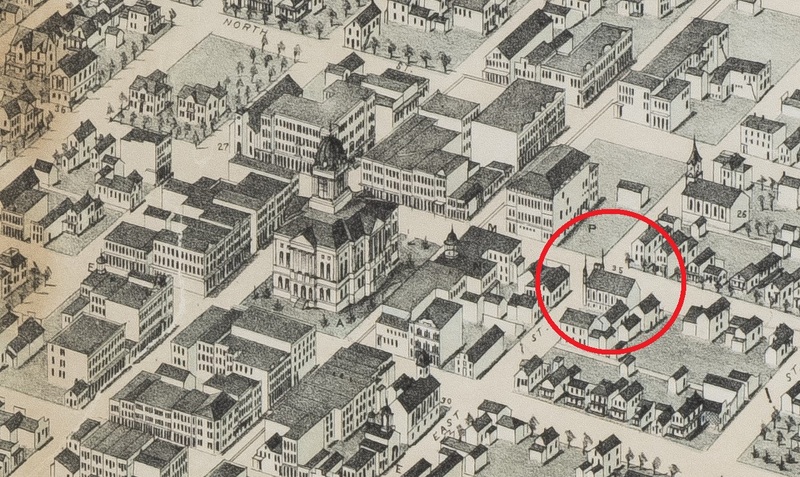

There are not yet sufficient materials from the years of the Civil War to determine how a pacifist like Charles dealt with this wholescale abandonment of the ideal of moral suasion. But the founding of the Free Congregational Society suggests one response. Far from a retreat into personal spirituality, the Free Congregational Society combined total freedom of religious belief with a commitment to radical social change. The speakers list is studded with names like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and their ilk. The list will be included in a later page on the Free Congregational Society.

Gertrude's death was a devestating loss.

VII. The Final Decade and Its Sudden End - Legacy

The last years of Charles Calistus Burleigh's life are still coming into focus, as the Burleigh team is undertaking a good deal of original research. Far from a quiet retirement, it appears that Charles Calistus Burleigh shifted his energy into "free" religion - religion cleared of dogma and open to perpetual question from any and all - as well as Temperance - which would seem to be at variance with the freedom he was articulating in religion. He also embraced the cause of Woman's rights and what was termed "Universal Suffrage" - giving the vote to all, regardless of race or sex. Most tantalizingly, he gave a series of 16 "Anti-Slavery Reminiscences" while serving as a minister at the Free Congregational Church of Bloomington, Illinois. It seems, therefore, that like many prominent Abolitionists, Charles C. Burleigh was contemplating a book-length memoir. This throws the tragedy of his sudden accidental death into high relief; unless extensive notes of his, or of someone in attendance in Bloomington, are discovered, we will have only hints of his own individual perspective on the events of the movement in which he played such a large part.

While the motivations for this move remain to be determined, in April of 1873 he arrived in Bloomington, Illinois, where he became the minister for that town's Free Congregational Church by May of that year. His "audition" sermon on April 13, 1873, was described thus in the local paper

“This able divine, whose reputation has long preceded him to the West...delivered a sermon of rare ability,...full of deep thought...well worthy of the man who many years ago fought the good fight of anti-slavery and temperance, with such good effect.”

The contrast between Burleigh and his predecessor - E. R. Sanborn - was a stark one. Sanborn was young, a veteran of the Civil War who had been wounded in the line of duty, and was particularly interesting to "the younger members of the church." As he was leaving, the local Bloomington paper lamented his departure, noting that the "congregation part with him with much regret, because of his estimable qualities as a man and his ability as a speaker." Obviously there would be no drop off in oratorical skill or moral rectitude with Charles C. Burleigh replacing him, but the contrast in age, looks, and experience had to be a sharp one. To make the transition even thornier, Sanborn stayed around a few weeks into Burleigh's time in Bloomington.

No matter what happened in the transition, C. C. Burleigh took to the role of full-time pastor with characteristic zeal. He officiated at weddings and funerals, made prison visitations, and prepared weekly sermons (some were broken into two-week sequences). The chart below gives a look at his time at Free Congregational church of Bloomington, week-to-week. [The Burleigh team hopes to fill in some of the missing data when a visit to Bloomington and the McLean Museum of History can be arranged].

References

"Rev. C. C. Burleigh," The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), April 9, 1873, p. 4,; April 14, 1873, page 4; and April 18, 1873, p. 3.

Daily Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), March 14, 1873, p. 3 (on Sanborn's departure)

"Death of E. R. Sanborn" The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), October 29, 1886, p. 4