Women's Rights

I. The Women of the Burleigh Family - by Birth

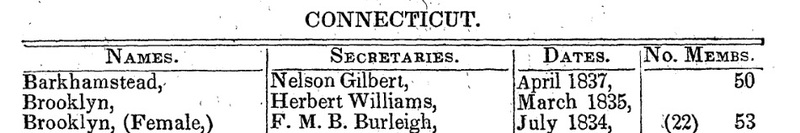

(Frances) Mary Burleigh (Ames) is the only surviving daughter among the core generation of siblings. However, she was also the oldest of the siblings, and universally beloved by her brothers. It is Mary who first endorses the Canterbury Female Academy by joining the Crandall sisters as a co-teacher. She is a co-founder and officer of the Brooklyn (Connecticut) Female Anti-Slavery Society, started when the Canterbury Academy was still flourishing, but continuing through the 1830s. Mary appears to have remained active in it through its known life span. There is also a tantalizing hint that she joined some of the Boston conversations with the Alcotts in the 1840s. When she and her husband Jesse Ames moved to Vineland, New Jersey in the 1860s and 1870s, that semi-utopic settlement was a hotbed of Woman Suffrage activity.

While the evidence assembled concerning Mary Burleigh feels whispy, like sand slipping through the fingers, it is also consistent with the profile of a Woman's Right activist. It seems possible that her constant domestic duties and elder care took her away from activism for much of the 1850s and 1860s (a situation parallel to that of Prudence Crandall, who had moved to Illinois). The search will continue.

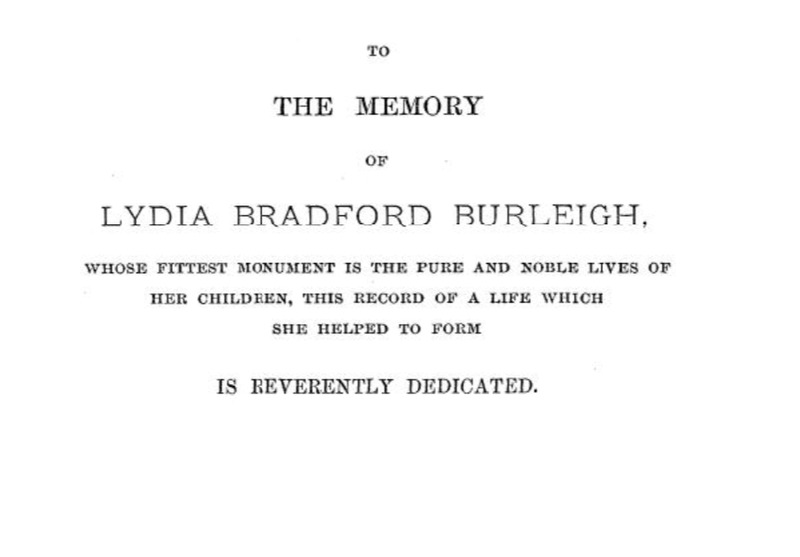

The mother of the Burleigh core siblings, Lydia Bradford Burleigh, is, as documented on her page, a profound influence on her children and their activism. While she is remembered with deep love by her children, a hint of how she lived a life of moral fortitude and a progressive vision can be discerned in the memorials offered by her son Charles, when he wrote in his obituary letter on her:

if her spirit could speak to me from its new abode, it would say to me, ‘Return to your work, and show your reverence for my memory by being true to the principles I instilled into you from infancy upward.’

Similarly, the dedicatory page of the posthumous edition of William Burleigh's poetry, edited by Celia Burleigh, pays homage to the moral guidance of Lydia Bradford Burleigh. It is not clear if it was William's idea, or Celia's, but to dedicate a book at the moment of your death, to your mother who has been gone for nearly twenty years, is not a common sentiment. Compare, for instance, the other more famed nineteenth-century Connecticut family - the Beechers. As talented, literate, and learnéd as Roxana Foote Beecher was, her talented children refer back to their father far more often than they do to her. The opposite is the case with the Burleigh family. As said on another page, the Burleigh siblings respected their father, but loved their mother, and mention her influence with far greater frequency than their father. While we cannot contend, from the available evidence, that Lydia Bradford Burleigh was in favor of Women's Rights per se, the image of an intellectually and morally powerful woman as the center of the Burleigh household, and as the source of her children's activism, means that the core generation of Burleigh siblings could not deny women's importance and centrality to the struggle without denying their own experience.

II. The Men of the Burleigh Family move toward Pro-Feminism

Many pro-feminist men come to support women's rights through observing the restrictions placed on the strong women in their own families. This is true of the men of the Burleigh family. Their mother Lydia, and their oldest sibling, Mary, were strong female figures in their lives. Despite this, though, the process for the men, towards embracing women's rights, was uneven.

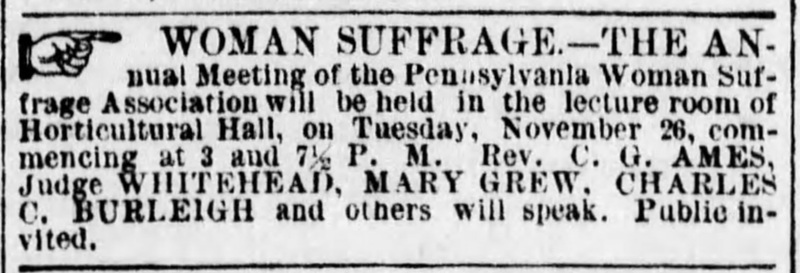

Charles Calistus Burleigh, perhaps because of his strong affiliation with Garrisonianism, and his work with Abby Kelley Foster, was among the earliest to endorse women's rights. He was active in the American Equal Rights Association in the aftermath of the Civil War. His marriage to the Quaker-raised Gertrude Kimber Burleigh, and his extensive time working with Quaker abolitionists in Pennsylvania, brought him to further appreciate the intellectual and oratorical powers of women. He attended women's suffrage conventions after the Civil War. Notably, he collaborated and shared the podium with many early women ministers - Lydia Ann Jenkins (Universalist), Antoinette Brown (Congregational), and his sister-in-law Celia Burleigh (Unitarian).

III. The Women of the Burleigh Family by Marriage

To Be Added Soon!

IV. The Angel of Monterey

The perception of women as morally superior to men was part of the gender ideology of the nineteenth-century. Scholars and present-day feminists often dismiss this as a form of sentimental essentialism. But this erases the profoundly disquieting effect on male supremacy that this moral ideology could have - especially to morally active agents of change like the Burleigh family.

A remarkable convergence of anti-war, anti-imperialism, and proto-feminism, thus occured when news reached the United States of the brave actions of mercy undertaken by Mexican women on the actual battlefield during the Mexican-American War. That war was condemned by Abolitionists and the reform movements in general; it famously bequeathed to us Thoreau's Civil Disobedience.

John Greenleaf Whitter's 1847 poem "The Angels of Buena Vista," exemplifies this convergence: it is one of the most important anti-war poems in his pacifist ouvere, and extols the women who can see the suffering on all sides, and even forget their own misery to tend to the dying of both sides.

Intriguingly, at the same moment, in 1847, George Shepard Burleigh and his older brother William were at the height of their skills as editorialists on the pages of The Charter Oak. While it is not yet clear if this is from George or William's pen, these scathing critique and seething anger at the Mexican-American War burn on the page. While this is admittedly the work of a sentimental nineteenth-century writer, for whom a good martyr narrative has deep emotional appeal, the effect of "Women on the War-Field" remains powerful. The first paragraphs parrot, then eviscerate, claims of Anglo-Saxon superiority. The focus shifts to womanhood - here defined in a standard nineteenth-century American gender ideology. A contrast is made between the American women in Massachusetts who loudly applauded the war effort, and the Mexican women who took their mission of mercy to the actual battlefield. Women are shown to be the only true Christians - an ideal that men, as a class, fall far short of. Women are not on a pedestal here - they are on a battlefield, and show their true humanity while being in extreme danger. Granted, the Burleighs idealized these women, little realizing that many of them were actually fighters, too (soldaderas). Ultimately though, this idealized contrast between bloodthirsty men - and the especially culpable American pro-slavery imperialists (including President Polk) - and women who had some sense of humanity - condemns the male perspective (which, as American white men, the Burleighs were a part of) and elevates the Mexican women. The work that this essay is doing goes well beyond any facile critique of its obvious shortcomings.

Note - the poem opens with some gross mischaraterizations of Mexicans as people. It is not clear, interpretively, if these are used sarcastically, or as a parody of what Americans were saying about their Mexican opponents, or if they represent a misstep by George Shepard Burleigh.

More materials will be added to this page in the coming year. Stop back soon!

Cyrus Moses Burleigh likewise adopted the Garrisonian line, and, like Charles, interacted extensively with the Philadelphia Quaker Abolitionists. Throughout his journals, his comments on women always look to their minds and moral fortitude, rather than their looks, or emotional sentimentality. His end-of-life interactions with Mary Grew and Margaret Jones, described elsewhere, point to an incipient understanding of queer gender dynamics.

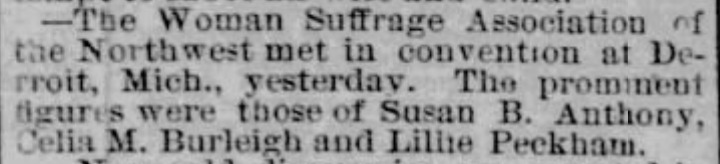

William Henry Burleigh's first marriage appeared to be conventional, but it is clear that Harriet was thinking along feminist lines, given her adoption of the Bloomer outfit and her speaking out at the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall. William's second wife, Celia Burleigh, is a major activist for women's rights, suffrage, and public speaking. She is most famous as a co-founder of the first woman's club, Sorosis, and as the first female Unitarian minister to hold a pulpit - that being in Brooklyn, Connecticut. Her influence on William's embrace of women's rights was vast.

George Shepard Burleigh, being a poet, always had references to women in his work - that range from the most conventional and sentimental, to genuinely empowering. His marriage to Ruth Burgess Burleigh also aided his recognition of women as agents of change. He often returned to the theme of girls, seeing great promise in their pluck and vision. His most important work of fiction - the serialized short story/novella "Effie Lee" - has two young girls, one white and one Black, as its protagonists. In his later years, his poetry was often addressed to the girls in the neighborhood of his Little Compton, Rhode Island, residence. Further analysis is needed to tease out what he was saying about girls and women, but during the post-Civil War era, he endorsed woman suffrage and woman's rights generally.

The Burleigh team has yet to uncover any solid evidence of explicit support for women's rights by Lucian Rinaldo Burleigh, John Oscar Burleigh, or Jesse Ames, but the research will continue!