Understanding the Temperance Cause

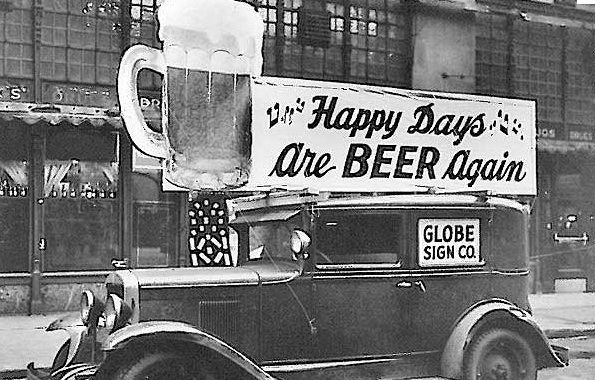

The intertwining of Temperance with all the other reform causes of the Benevolent Empire in the 19th century is, from our contemporary perspective, puzzling. We know how this reform turned out - or we think we do. The forces of Temperance finally won their victory with a constitutional Prohibition Amendment to the Constitution (the Eighteenth Amendment), passed in 1919 and becoming law in 1920. The result was a chaotic flouting of the law during the Roaring Twenties, an increase in crime - and in heavy-handed moral policing - and finally an urgent movement to repeal the hated 18th. Prohibition's repeal happened, and was widely celebrated, with the Twenty-first Amendment in 1933. As a result of this astonishing accelerated arc of success and failure from 1919 to 1933, Temperance has been rendered a cautionary tale. Its roots in the Benevolent Empire are all but lost in the haze surrounding its later linkage of moral policing, religion, and government overreach.

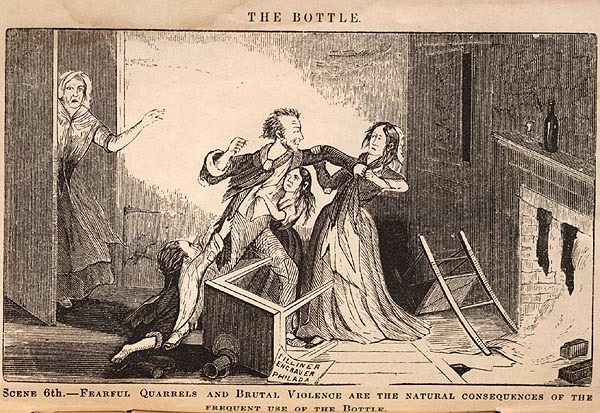

While the Temperance cause is now widely perceived as a failure, yet there are reasons to review its rationale and impact. We still regulate alcohol, and discourage excessive consumption (Mothers Against Drunk Driving, criminal penalties for drunk driving, the documented impact of alcoholism in domestic violence, etc.). There is also ample evidence that alcohol consumption in the United States in the 19th century was excessive, because alcoholic beverages were generally safer to drink than most beverages made from water. So the Temperance advocates may have had a reasonable cause — attempting to limit the damage to families and lives caused by alcohol — but an unreasonable solution — total prohibition.

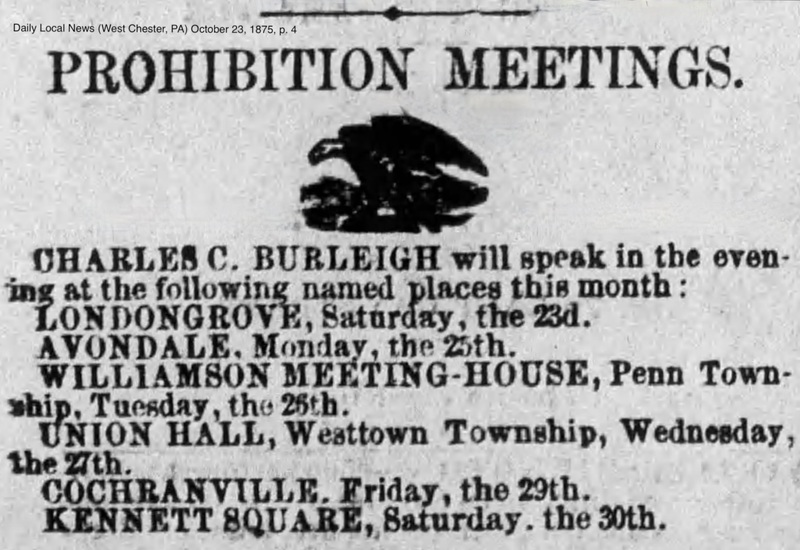

The siblings were deeply committed to the Temperance cause. The five most public of the Burleigh siblings were all ardent Temperance advocates. William, Lucien, and Cyrus all worked as agents and/or editors for Temperance organizations. John and his wife Evelina practiced Temperance principles, as did Mary and Jesse Ames. George Shepard Burleigh wrote many Temperance poems. Charles was less directly engaged with Temperance than with Abolition, but after the Civil War he stepped up his Temperance advocacy, and stumped for the Prohibition Party ticket in Pennsylvania in 1875.

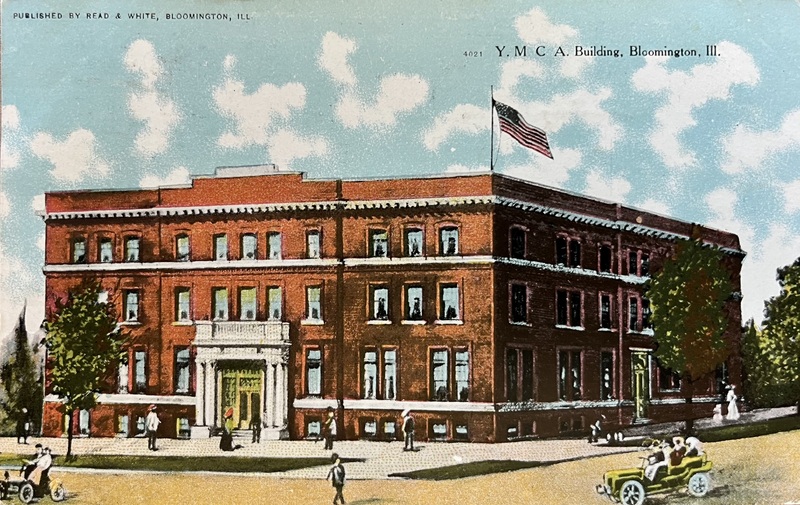

In his Temperance activism in the 1870s, Charles C. Burleigh was explicitly in favor of governmental Prohibition. In an 1874 speech at the Y.M.C.A. Building in Bloomington, Illinois, for instance, he states that "the liquor men are blasting the hopes and WITHERING THE MANHOOD OF THOUSANDS of his brothers." The unnamed author of the article continues by noting that "(p)rohibitory laws can be and are enforced. In the liquor traffic prohibition can be enforced as well as legislation against other kinds of immorality. The law should be the auxiliary of moral influence.” Whether Burleigh himself said those words, or if this was the interpretation of the person who heard the speech, is unclear. But the arguments of Burleigh are already sliding down the slippery slope of legislating personal morality. By contrast, outlawing slavery was about human rights, addressing an issue that affected the humanity and social contract of everyone in the nation.

Sources

No author named. “The Campaign Opens: Enthusiastic Temperance Meetings Last Night,” The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), March 13, 1874, p. 4

The Temperance and Anti-Slavery movements both engaged in what we would now call "consumer-driven" activism. For the Anti-slavery cause, this was marked by the Free Produce movement: the sale of food and goods produced without enslaved labor. For Temperance activists, Temperance Hotels became a feature in most major cities. Both of these strategies encountered difficulties in wide-spread acceptance, because the products/hotels were often perceived, even by friends, of being of inferior quality, or too expensive to justify. But the two movements were so closely intertwined that these major engines of consumer activism were often mutually shared. Abolitionists certainly understood the connections between rum and slavery, so it is not suprising that Abolitionist newspapers frequently advertised Temperance hotels.

Sources

Julie L. Holcomb. Moral Commerce: Quakers and the Transatlantic Boycott of the Slave Labor Economy. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2016.

"Tremont Temperance House - Messrs. Burt & Taylor, the former recently of the Exchange Hotel, Hartford, have leased the spacious building No. 110 Broadway, known as the Tremont House, and have renovated and refurnished it in excellent style, with the determination to keep a Hotel upon strict Temperance principles that shall be worthy of the liberal patronage of the Temperance community. If gentlemanly landlords, attentive and active servants, pleasant and airy rooms, and a table abundantly supplied with the delicacies of the season, have attractions for the sojourner or the traveler, they all can be found here. The great improvement in the character of Temperance Houses which has taken place within a few years, furnishes gratifying evidence of the progress of the good cause. A Temperance man need no longer stop at a liquor tavern in order to be comfortably accomodated. Let the liberality of the proprietors be met by a correspondingly liberal patronage on the part of the friends of Temperance."We clip the above from the New York Tribune, and from our personal experience and observation, can respond to its commendations. We ask for it the attention of our Temperance friends, who may have occasion to visit New-York. At the Tremont Temperance House they will find as good quarters as reasonable men can desire, an abundance of the best the market affords, and — a consideration worthy of some attention — reasonable bills. We know of some very zealous Temperance men in Hartford and vicinity who, when they visit New-York, patronise the liquor hotels in preference to Temperance Houses. This is neither consistent nor politic. Temperance Hotels cannot be sustained without patronage—and there is a large class of the traveling community who will not stop at such houses, because of the absence of intoxicating drinks. They are, therefore, compelled to rely mainly upon the temperance community for support—and if temperance men prefer the rum taverns, the temperance houses, of course, cannot be sustained. We ask our readers to think of this matter, and act accordingly.The Tremont Temperance House is kept by two Hartford men—Messrs. Burt & Taylor. Mr. Burt was for some time connected with the Exchange Hotel on State street, and was well known as an efficient and accomodating landlord. Let not his old Hartford friends forget him when they visit the Commercial Emporium. His present quarters — corner of Broadway and Pine — are pleasant, commodius, and convenient to the business part of the city.

-- William Henry Burleigh, in his capacity as editor of the Anti-Slavery newspaper, The Charter Oak, New Series vol. 1 no. 31 (August 6 ,1846)

Temperance Poetry

Both William Henry Burleigh and George Shepard Burleigh composed Temperance poems and songs. Some of these were intended for children; all were aimed at the "Cold Water Army." These poems were often collected into short books and pamphlets, for easy use in church and meeting settings.

When next you are thirsty, it brings an added delight to the mind to know that the ubiquity of public water fountains is a gift we owe the Temperance movement! History has many contradictions, after all, but at least this one allows you to "obey your thirst!"

The Temperance movement also provided a fertile ground for woman suffrage activism. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and Mary Ann McCurdy were some of the African-American women activists who used the organizing energy of temperance to further support for suffrage in Black communities.

Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1998. p. 84-86.

Black Abolitionists and Temperance

Class Dimensions and Anti-Catholicism in Temperance movement

Women's Perspectives on Temperance

Cyrus's Diary and the Battle of Plainfield over Liquor Licenses

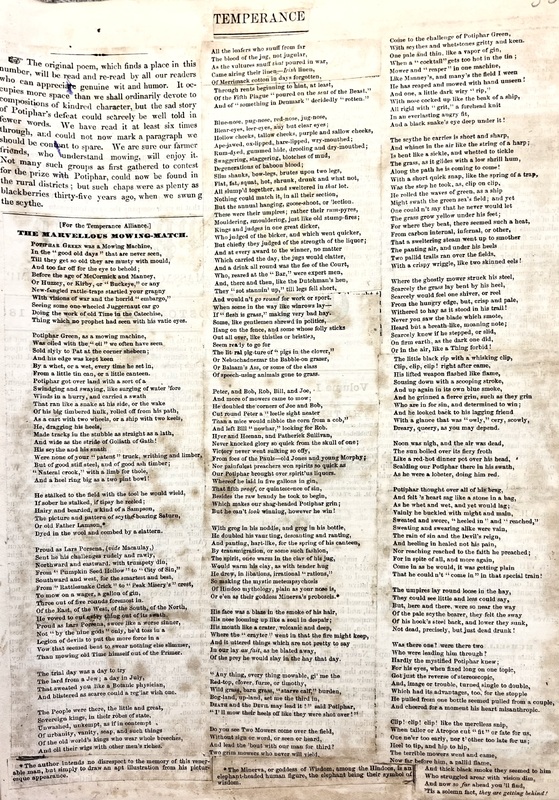

TEMPERANCE

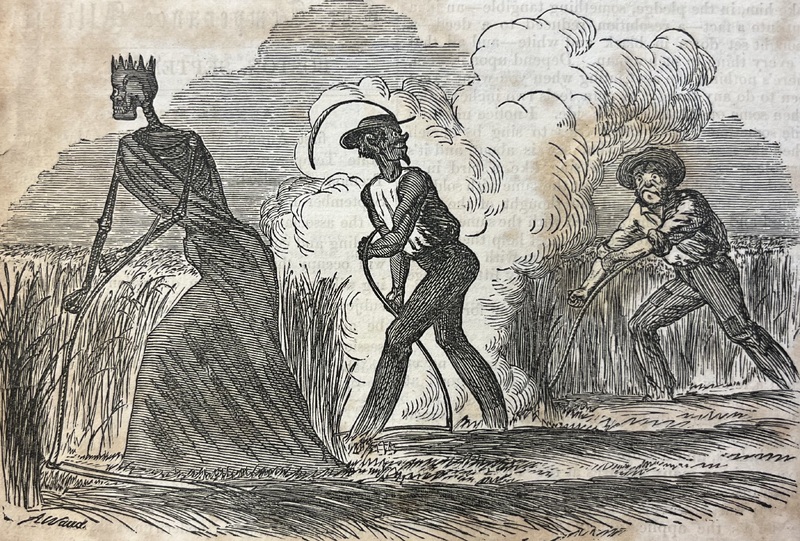

☞ The original poem, which finds a place in this number, will be read and re-read by all our readers who can apprecia t e genuine wit and humor. It occupies more space than we shall ordinarily devote to compositions of kindred character, but the sad story of Potiphar’s defeat could scarcely be well told in fewer words. We have read it at least six times through, and could not now mark a paragraph we should be con te nt to spare. We are sure our farmer friends, who understand mowing, will enjoy it. Not many such groups as first gathered to contest for the prize with Potiphar, could now be found in the rural districts; but such chaps were as plenty as blackberries thirty-five years ago, when we swung the scythe.

[For the Temperance Alliance.]

THE MARVELLOUS MOWING-MATCH.

POTIPHAR GREEN was a Mowing Machine,

In the “good old days” that are never seen,

Till they get so old they are musty with mould,

And too far off for the eye to behold;

Before the age of McCormick and Manney,

Or Huzzey or Kirby, or “Buckeye,” or any

New-fangled rattle-traps startled your granny

With visions of war and the horrid “embargo,”

Seeing some one-wheeled Juggernaut car go

Doing the work of old Time in the Catechise,

Thing which no prophet had seen with his vatic eyes.

Potiphar Green, as a mowing machine,

Was oiled with the “oil” we often have seen

Sold slyly to Pat at the corner shebeem;

And his edge was kept keen

By a whet, or a wet, every time he set in,

From a little tin can, or a little canteen.

Potiphar got over land with a sort of a

Swindging and swaying, like surging of water ‘fore

Winds in a hurry, and carried a swath

That ran like a snake at his side, or the wake

Of his big timbered hulk, rolled off from his path,

As a cart with two wheels, or a ship with two keels,

He, dragging his heels,

Made tracks in the stubble as straight as a lath,

And wide as the stride of Goliath of Gath!

His scythe and his snath

Were none of your “patient” truck, writhing and limber,

But of good stiff steel, and of good ash timber;

“Natural crook,” with a limb for those,

And a heel ring big as a two pint bowl!

He stalked to the field with the tool he would wield,

If sober he stalked, if tipsy he reeled;

Hairy and bearded, a kind of a Sampson,

The picture and pattern of scythe-bearing Saturn,

Or odd Father Lamson ,*

Dyed in the wool and combed by a slattern.

Proud as Lars Porsena, ( vide Macaulay,)

Sent he his challenges rudely and rawly,

Northward and eastward, with trumpety din,

From “Pumpkin Seed Hollow” to “City of Sin,”

Southward and west, for the smartest and best,

From “Rattlesnake Crick” to “Peak Misery’s” crest,

To mow on a wager, a gallon of gin,

Three out of five rounds foremost in.

Of the East, of the West, of the South, of the North,

He vowed to cut every thing out of its swath.

Proud as Lars Porsena, swore like a worse sinner,

Not “by the nine gods” only, he’d toss in a

Legion of devils to put the more force in a

Vow that seemed best to swear nothing else slimmer,

Than mowing old Time himself out of the Primer.

The trial day was a day to try

The lard from a Jew; a day in July,

That sweated you like a Botaide physician,

And blistered as scarce could a reg’lar wish one.

The People were there, the little and great,

Sovereign kings, in their robes of state,

Unwashed, unkempt, as if in contempt

Of urbanity, vanity, soap, and such things

Of the odd world’s kings who wear whole breeches,

And oil their wigs with other men’s riches.

All the loafers who snuff from far

The blood of the jug, not jugular,

As the vultures snuff that poured in war,

Came airing their linen — Irish linen,

Of Merrimack cotton in days forgotten,

Through rests beginning to hint, at least,

Of the Fifth Plague “poured on the ? of the Beast,”

And of “something in Denmark” decidedly “rotten.”

Blue-nose, pug-nose, red-nose, jug-nose,

Blear-eyes, leer-eyes, any but clear eyes;

Hollow cheeks, tallow cheeks, purple and sallow cheeks,

Ape-jawed, ox-lipped, hare-lipped, wry-mouthed;

Swaggering, staggering, blotches of mud,

Degenerations of baboon blood;

? shanks, bow-legs, brutes upon two legs,

Flat, fat, squat, hot, shrunk, drunk and what not,

All slump’d together, and sweltered in that lot.

Nothing could match it, in all their section,

But hte annual hanging, goose-shoot, or ‘lection.

These were their umpires; rather their rum-pyres,

Mouldering, smouldering, just like old stump-fires;

Kings and judges in one great dicker,

Who judged of the bicker, and which went quicker,

But chiefly they judged of the strength of the liquor;

And at every award to the winner, no matter

Which carried the day, the jugs would clatter,

And a drink all round was the fee of the Court,

Who, reared at the “Bar,” were expert men,

And, there and then, like the Dutchman’s hen,

They “set stannin’ up,” till legs fell short,

And wouldn’t go round for work or sport,

When some in the way like winrows lay —

If “flesh is grass,” making very bad hay,

Some, like gentlemen shrewd in politics,

Hang on the fence, and some whose folly sticks

Out all over, like thistles or bristles,

Seem really to go for

The literal pig-ture of “pigs in the clover,”

Or Nebuchadnezzar the Babble-on graner,

Or Balsam’s Ass, or some of the class

Of speech- ? animals gone to grass.

Peter, and Bob, Rob, Bill, and Joe,

And more of mowers came to mow;

He doubted the corners of Joe and Bob,

Cut round Peter a “leetle sight neater

Than a mice would nibble the corn from a cob,”

And left Bill “nowhar,” looking for Rob.

Hyer and Heenan, and Patherick Sullivan,

Never knocked glory so quick from the skull of one;

Victory never went sulking so offy,

From foes of the Pauls — old Jones and young Morphy;

Nor painfulest preachers won spirits so quick as

Our Potiphar brought over spirit’us liquors.

Whereof he laid in five gallons of gin,

That fifth proof , or quintescence of sin,

Besides the raw brandy he took to begin,

Which makes our shag-headed Potiphar grin;

But he can’t look winning, however he win!

With grog in his noddle, and grog in his bottle,

He doubled his vaurting, descanting and ranting,

And panting, hart-like, for the spring of his canteen,

By transmigration, or some such fashion,

The spirit, once warm in the clay of his jug,

Would warm his clay, as with tender hug

He drew, in libations, irrational “rations,”

So making the mystic metempsychosis

Of Hindoo mythology, plain as your nose is,

Or e’en as their goddess Minerva’s proboscis.**

His face was a blaze in the smoke of his hair,

His nose looming up like a soul in despair;

His mouth lik ea crater, volcanic and deep,

Where the “crayter” went in that the fire might keep,

And it uttered things which are not pretty to say

In our lay au fait , as he blasted away,

Of the prey he would slay in the hay that day.

“Any thing, every thing movable, gi’ me the

Red-top, clover, furze, or timothy,

Wild grass, barn grass, “starve calf,” burden,

Bog-land, up-land, set me the third in,

DEATH and the DEVIL may lead it!” said Potiphar

“I’ll mow their heels off like they were shot over!”

Do you see Two Mowers come over the field,

Without sign or word, or seen or heard,

And lead the ‘bout with our man for third?

Two grim mowers who never will yield,

Come to the challenge of Potiphar Green,

With scythes and whetstones gritty and keen.

One pale and thin, like a vapor of gin,

When a “cocktail” gets too hot in the tin;

Mower and “reaper” in one machine,

Like Manney’s, and many’s in the field I ween

He has reaped and mowed with hand unseen!

And one, a little dark wiry “rip,”

With nose cocked up like the beak of a ship,

All rigid with “grit,” a forehead knit

In an everlasting angry fit,

And a black snake’s eye deep under it!

The scythe he carries is short and sharp,

And whines in the air like the string of a harp;

Is bent like a sickle, and whetted to tickle

The grass, as it glides with a low shrill hum,

Along the path he is coming to come!

With a short quick snap, like the spring of a trap,

Was the step he took, as, clip on clip.

He rolled the waves of green, as a ship

Might swath the green sea’s field; and yet

One couldn’t say that he never would let

The grass grow yellow under his feet;

For where they beat, there seemed such a heat,

From carbon internal, infernal, or other,

That a sweltering steam went up to smother

The panting air, and under his heels

Two pallid trails ran over the fields,

With a crispy wriggle, like two skinned eels!

Where the ghostly mower struck his steel,

Scarcely the grass lay bent by his heel,

Scarcely would feel one shiver, or reel

From the hungry edge, but, crisp and pale,

Withered to hay as it stood in his trail!

Never you saw the blade which smote,

Heard but a breath-like, moaning note;

Scarcely knew if he stepped, or slid,

On firm earth, as the dark one did,

Or in the air, like a Thing forbid!

The little black rip with a whisking clip,

Clip, clip, clip! right after he came,

His lifted weapon flashed like flame,

Sousing down with a scooping stroke,

And up again in its own blue smoke,

And he grinned a fierce grin, such as they grin

Who are in for sin, and determined to win;

And he looked back to his lagging friend

With a glance that was “owly,” cery, scowly,

Dreary, queery, as you may depend.

Noon was nigh, and the air was dead,

The sun boiled over its fiery froth

Like a red-hot dinner pot over his head,

Scalding over Potiphar there in his swath,

As he were a lobster, doing him red.

Potiphar thought over all of his brag,

And felt ‘s heart sag like a stone in a bag,

As he whet and wet, and yet would lag;

Vainly he buckled with might and main,

Sweated and swore, “heeled in” and “reached,”

Sweating and swearing alike were vain,

The rain of sin and the Devil’s reign,

And heeling in healed not his pain,

Nor reaching reached to the faith he preached;

For in spite of all, and more again,

Com in as he would, it was getting plain

That he couldn’t “come in” in that special train!

The umpires lay round loose in the hay,

They could see little and less could say,

But, here and there, were so near the way

Of his pale scythe bearer, they felt the sway

Of his hook’s steel back, and lower they sunk,

Not dead, precisely, but just dead drunk!

Was there one? were there two

Who were leading him through?

Hardly the mystified Potiphar knew;

For his eyes, when fixed long on one tople,

Got just the reverse of stereoscopic,

And, image or trouble, turned single to double,

Which had its advantages, too, for the stopple

He pulled from one bottle seemed pulled from a couple,

And cheered for a moment his heart misanthropic.

Clip! clip! clip! like the merciless snip,

When tailor or Atropos cut “fit” or fate for us,

One ne’er too early, nor t’ other too late for us;

Heel to tip, and hip to hip,

The terrible mowers went and came,

Now far before him, a pallid flame,

And thick black smoke they seemed to him

Who struggled arear with vision dim,

And now so far ahead you’ll find,

‘Tis a solemn fact, they are getting behind!

*The author intends no disrespect to the memory of this venerable man, but simply to draw an apt illustration from his picturesque appearance.

**The Minerva, or goddess of Wisdom, among the Hindoos, is an elephant-headed human figure, the elephant being their symbol of wisdom.

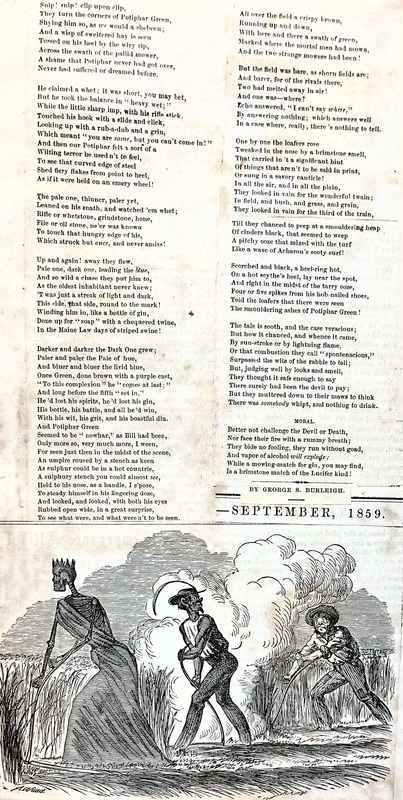

338

Sulp! sulp! clip upon clip,

They turn the corners of Potiphar Green,

Shying him so, as one would a shebeen ;

And a wisp of sweltered hay is seen

Tossed on his heel by the wiry rip,

Across the swath of the pallid mower,

A shame that Potiphar never had got over,

Never had suffered or dreamed before.

He claimed a whet; it was short, you may bet,

But he took the balance in “heavy wet;”

While the little sharp imp, with his rifle stick

Touched his hook with a slide and click,

Looking up with a rub-a-dub and a grin,

Which meant “you are ? , but you can’t come in!”

And then our Potiphar felt a sort of a

Whitling terror he used n’t to feel,

To see that curved edge of steel

Shed fiery flakes from point to heel,

As if it were held on an emery wheel!

The pale one, thinner, paler yet,

Leaned on his snath, and watched ‘em whet;

Rifle or whetstone, grindstone, hone,

File or oil stone, ne’er was known

To touch that hungry edge of his,

Which struck but once, and never amiss!

Up and again! away they flew,

Pale one, dark one, leading the blue ,

And so wild a chase they put him to,

As the eldest inhabitant never knew;

‘T was just a streak of light and dark,

This side, that side, round to the mark!

Winding him in, like a battle of gin,

Done up for “soap” with a chequered twine,

In the Maine Law days of striped swine!

Darker and darker the Dark One grew;

Paler and paler the Pale of hue,

And bluer and bluer the livid blue,

Once Green, done brown with a purple cast,

“To this complexion “he” ‘comes at last;”

And long before the fifth “set he,”

He’d lost his spirits, he’d lost his gin,

His bottle, his battle, and all he’d win,

With his wit, his grit, and his boastful din.

And Potiphar Green

Seemed to be “nowhar,” as Bill had been,

Only more so, very much more, I ween,

For seen just then in the midst of the scene,

An umpire roused by a stench as keen

As sulphur could be in a hot countrie,

A sulphury stench you could almost see ,

Held to his nose, as a handle, I s’pose,

To steady himself in his lingering dose,

And looked, and looked, with both his eyes

Rubbed open wide, in a great surprise,

To see what were, and what weren’t to be seen.

All over the field a crispy brown,

Rounding up and down,

With here and there a swath of green,

Marked where the mortal man had mown,

And the two strange mowers had been!

But the field was bare, as shorn fields are;

And barer, for of the rivals there,

Two had melted away in air!

And one was — where?

Echo answered “I can’t say where,”

By answering s?ing ; which answers well

In a case where, really, there’s nothing to tell.

One by one the loafers rose

Tweaked is the nose by a brimstone smell,

That carried in ‘t a significant hint

Of things that are n’t to be said in print,

Or sung in a savory canticle!

In all the air, and in all the plain,

They looked in vain for the wonderful twain;

In field, and bush, and grass, and grain,

They looked in vain for the third of the twain,

Till they chanced to peep at a smouldering heap

Of cinders black, that seemed to weep

A plitchy ooze that mixed with the turf

Like a wave of Acharon’s sooty surf!

Scorched and black, a heel-ring hot,

On a hot scythe’s heel, lay near the spot,

And right in the midst of the tarry ooze ,

Four or five spikes from his hob-nailed shoes,

Told the loafers that there were seen

The smouldering ashes of Potiphar Green!

The tale is sooth, and the case veracious;

But how it chanced, and whence it came,

By sun-strike or by lightning flame,

Or that combustion they call “spontaneous,”

Surpassed the wits of the rabble to tell;

But, judging well by looks and smell,

They thought it safe enough to say

There surely had been the devil to pay;

But they sauntered down to their maws to think

There was somebody whipt, and nothing to drink.

MORAL.

Better not challenge the Devil or Death,

Nor face their fire with a rummy breath;

They bide no fooling, they run without goad,

And vapor of alcohol will explode ;

While a mowing-match for gin, you may find,

Is a brimstone match of the Lucifer kind!

BY GEORGE S. BURLEIGH.

SEPTEMBER, 1859.