Newspapers Edited by Burleighs

William Burleigh tried his hand at farming and briefly attempted work at the village dyer establishment, before deciding on writing and newspaper work as a career. In 1829, he was apprenticed to the Norwich Republican and Stonington Telegraph in New London county, Connecticut, a bit south of Plainfield. He enjoyed the work, but did not enjoy his immediate supervisor, the presciently named William Faulkner (1808-1878). Faulkner later claimed that he had to fire William Burleigh for disobedience, while Burleigh implied that he quit before he was fired (Downing, 6).

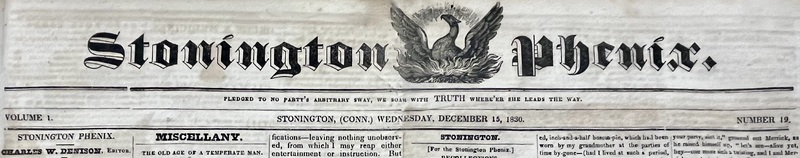

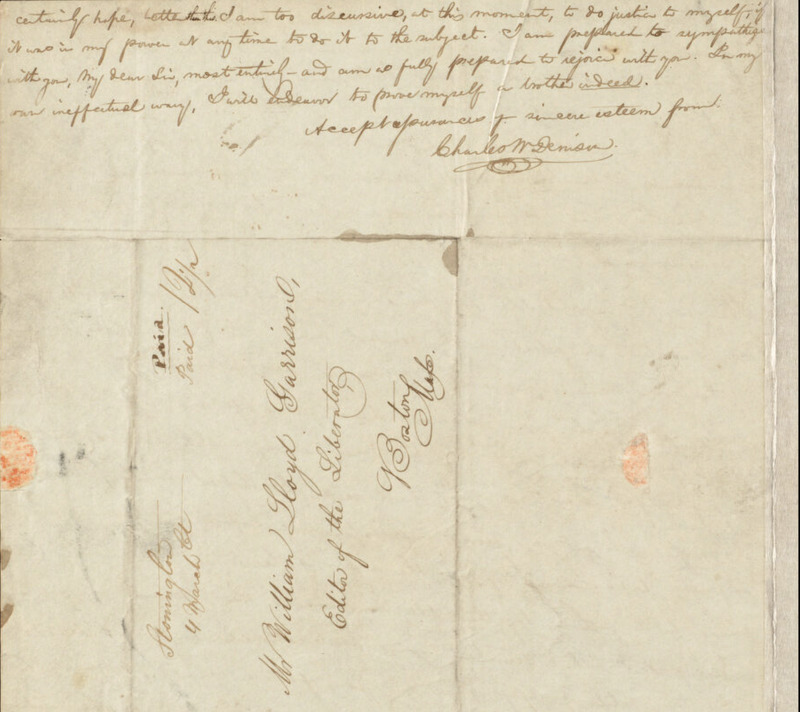

William Burleigh's next two positions as a journeyman printer were far more congenial, and provided him with life-long networks in reform communities. In 1830 he was hired by Charles Denison to assist in the publication of The Stonington Phenix. This newspaper - brief-lived, like many of Denison's projects would prove to be - was ironically the opposite of a Phenix, being more like a herald of the coming Immediate Abolition movement than anything arising from the ashes. In Denison, Burleigh found a kindred spirit, and was also privy to some of the first positive notices of the work of another young editor, William Lloyd Garrison, whose exploits in Baltimore (as part of Benjamin Lundy's editorial staff for The Genius of Universal Emancipation) and in the first issue of The Liberator, were eagerly followed in The Stonington Phenix. There were additional reform causes espoused, most importantly labor rights and temperance.

While Burleigh's pieces are not signed by him, I am suspicious that his identity lurks behind the pseudonym Inisfail. (more here) This is especially true when the editor is away, and Burleigh's characteristic sense of humor as a writer takes over.

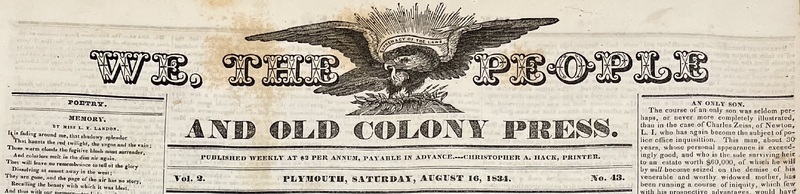

Prior to his work on The Unionist, Charles Calistus Burleigh played a small and (to our knowledge so far) anonymous role in helping to edit We, the People, and Old Colony Press, an Anti-Masonic newspaper in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where he was studying law. The prospectus for the paper indicates that "several literary gentlemen will render their voluntary assistance;" this is presumed to include Charles C. Burleigh. The time period would have been in 1832, possibly extending into the first month or so of 1833. We, the People, and Old Colony Press consistently supported the Canterbury Female Academy; I suspect they were in direct contact with Charles C. Burleigh during that time. In her brief biography of her husband, Gertrude Kimber Burleigh specifically mentions his working on this paper. William would later briefly work for the succeeding volume of this paper; see below.

Propectus from We, the People, and Old Colony Press 1:4 (November 17, 1832). Copy held at the American Antiquarian Society.

Letter from Gertrude K. Burleigh to Samuel May Jr., November 14, 1857. Copy held at Boston Public Library.

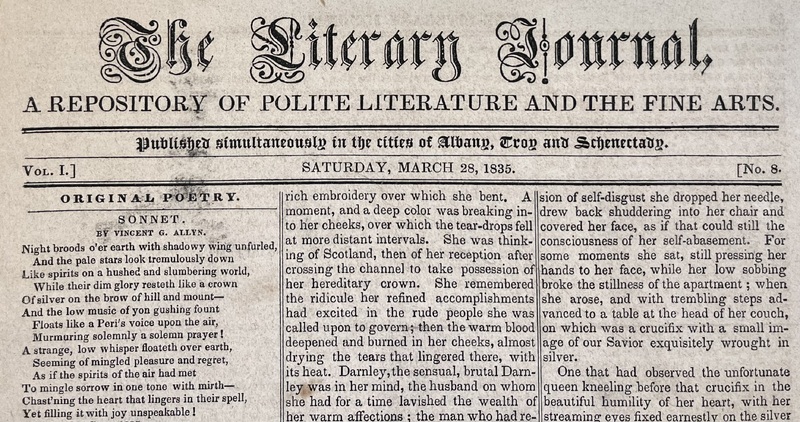

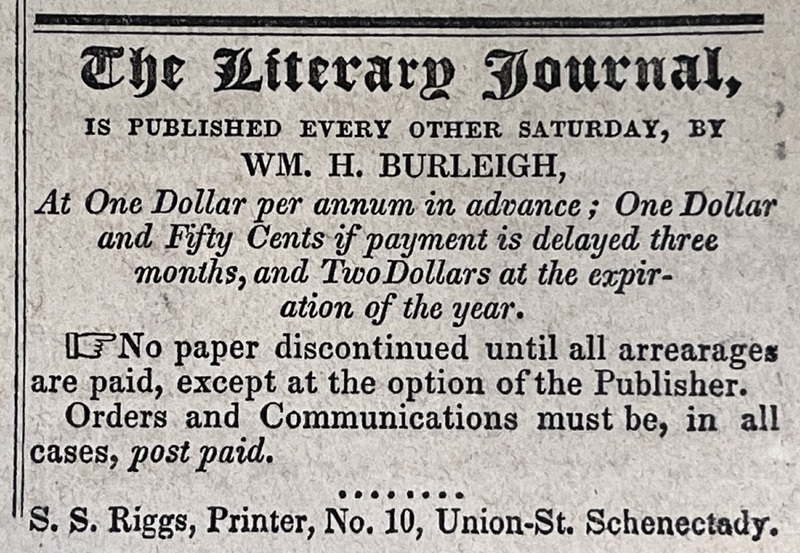

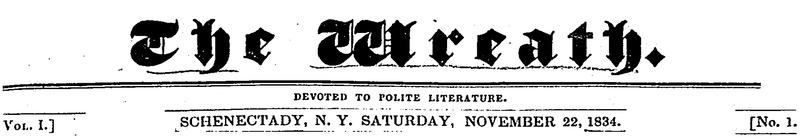

Stephen Riggs was also wiling to help William Henry Burleigh's ambitions to launch a literary monthly. In its initial iteration it was known as The Wreath. Later it morphed into The Literary Journal, and after William's move to Massachusetts it combined with a literary newspaper there, changing its name once again, this time to The Amaranth and Literary Journal. This sort of frequent re-naming is frustratingly common in 19th century America, and creates honest confusion even among scholars.

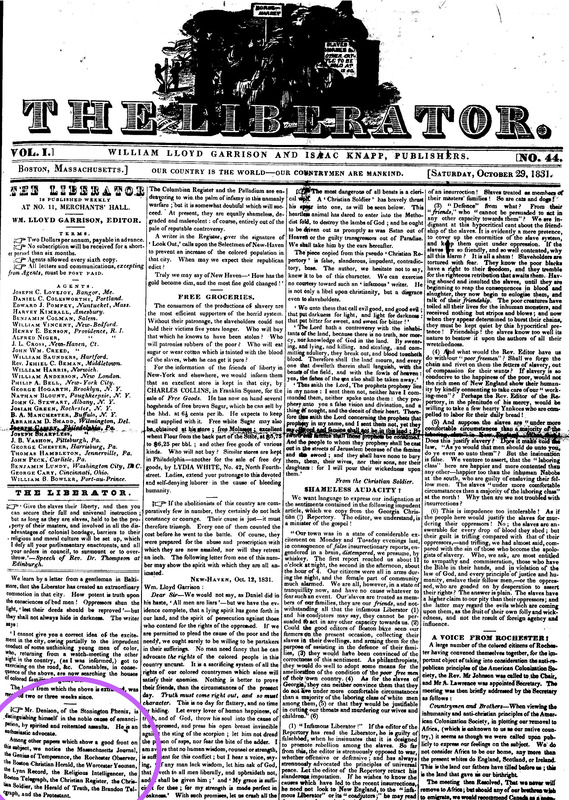

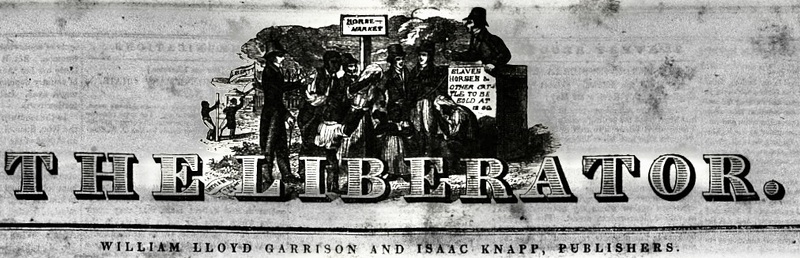

While William Burleigh headed to New York State, Charles Calistus Burleigh went to Boston after the crisis in Canterbury. He proved invaluable to the famed editor of The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison. In fact, Charles Burleigh was with Garrison on that fateful day when a Boston anti-abolitionist mob tried to assault Garrison: October 21, 1835. After Garrison survived this incident (by spending a night in the safety of a prison cell), he wisely decided to get out of Boston and spend some time at his in-law's, the Benson family, in Brooklyn, Connecticut. While Garrison was gone, most of the editorial duties for The Liberator devolved upon Charles Burleigh and Isaac Knapp. Burleigh wrote the lead article describing the incidents of October 21, and, for the year between October 1835 and October 1836, was often left in charge of this bellweather Abolitionist voice. Garrison bestowed high praise on Burleigh's efforts during this time.

See The Liberator 05:43:171 (October 24, 1835)

Henry Mayer. All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. (New York: St, Martin's Press, 1998), 200-201.

The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, Volume II: A House Dividing Against Itself, 1836-1840. Edited by Louis Ruchames. (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), 1-2.

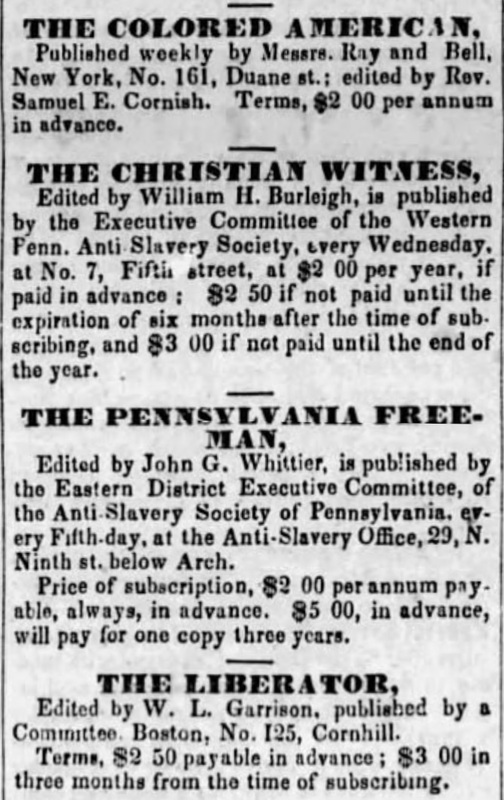

After working for a time as an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, William Henry Burleigh answered the call to edit an anti-slavery newspaper in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, entitled The Christian Witness (to which title was added and Temperance Banner - reflecting William's twin reform concerns). There is evidence that he was well-liked in western Pennsylvania, but equal evidence that he was underpaid. For a man with a growing family, that proved to be too much strain, and so he returned to Connecticut in the early 1840s. This needs more data.

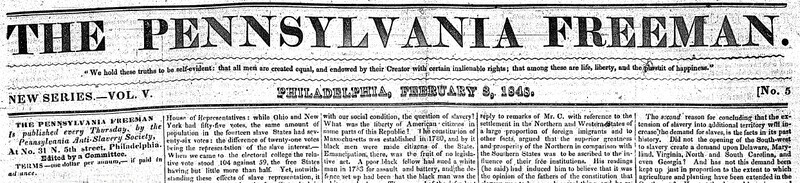

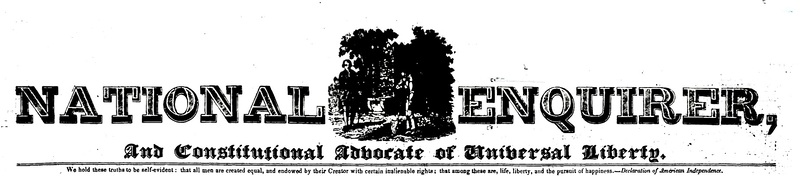

The National Enquirer, edited by Benjamin Lundy, was the journalistic voice of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (*check name). In the time period of 1837-38, Charles C. Burleigh assisted in its editing. This included the construction and destruction of Pennsylvania Hall.

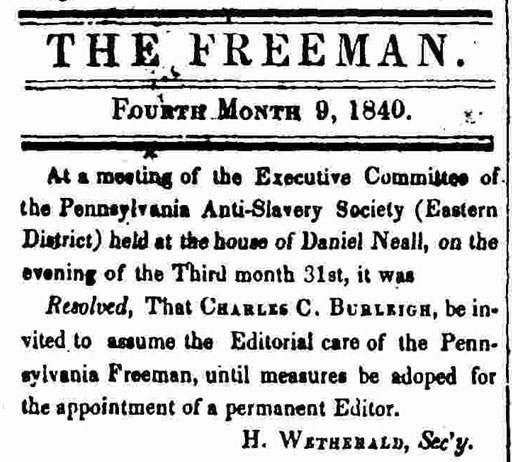

The editorship of The Pennsylvania Freeman evolved over the years, with a distinguished succession of editors - Benjamin Lundy, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Charles C. Burleigh. It then switched to a committee editorship, in which both Charles and Cyrus Moses Burleigh participated for many years, as well as Cyrus's friend and (briefly) wife, Margaret Jones Burleigh.

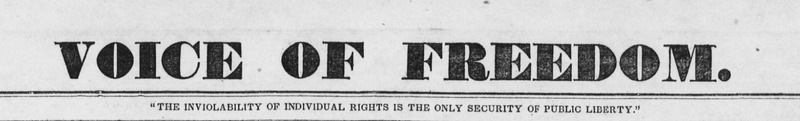

Voice of Freedom in Vermont June 1842 to June 1843 Charles worked in the Green Mountain State and edited their newspaper. So far, no extant issues during the time of Charles' tenure have been found.

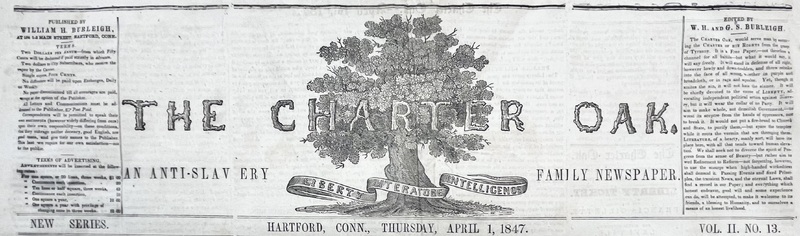

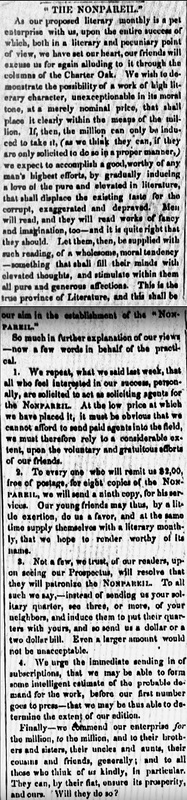

The Charter Oak named both William and George as editors. This undated prospectus in George's scrapbooks indicate his authorship, but also reveals much about the aesthetic philosophy of the brothers, and their attempt to walk the fine line of Abolitionist schism:

The Charter Oak, would serve man by securing the CHARTER OF HIS RIGHTS from the grasp of Tyranny. It is a Free Paper,—not therefore a channel for all babble—but what it would say, it will say freely. It will stand in defense of all right, however lowly and down-trodden, and throw rebuke into the face of all wrong, whether in purple and broadcloth, or in rags and squalor. Yet, though it smites the sin, it will not hate the sinner. It will be chiefly devoted to the cause of LIBERTY, advocating independent political action against Slavery, but it will wear the collar of no Party. It will aim to make whole, not demolish Government,—to wrest the sceptre from the hands of oppressors, not to break it. It would not put a fire-brand to Church and State, to purify them,—but spare the temples while it routs the vermin that are thronging them. LITERATURE, of a hearty, manly sort, will have its place here, with all that tends toward human elevation. We shall seek not to divorce the spirit of Progress from the sense of Beauty—but rather aim to wed Refinement to Reform‚ not forgetting, however, to use the scourge when high-handed wickedness shall demand it. Passing Events and fixed Principles, the transient News, and the eternal Laws, shall find a record in our Paper; and everything which honest endeavor, good will and some experience can do, will be attempted, to make it welcome to its friends, a blessing to Humanity, and to ourselves a means of an honest livelihood.

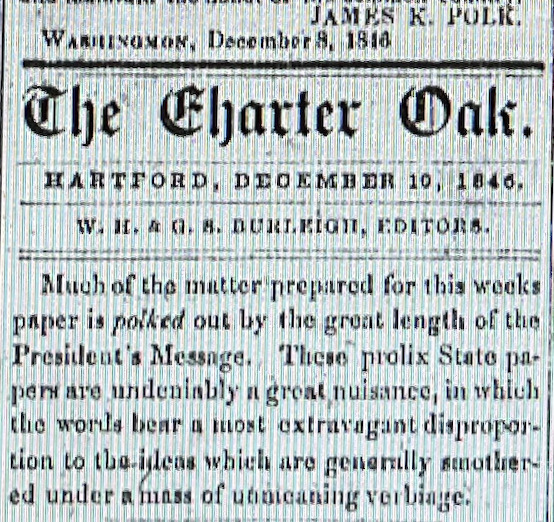

The Charter Oak started listing George S. Burleigh as a co-editor with William in the issue of November 26, 1846 (Charter Oak New Series 1:47:2). This was in the midst of the war against Mexico, which both brothers opposed. In the December 10 issue, they published President Polk's message to the nation, but not without a pun and a pointed jab at the President's lack of literary style.

William was always engaged in Temperance as well as Anti-Slavery, and in 1850 (check) answered a call from the New York Temperance Society (check) to edit their periodical, The Prohibitionist. He moved to Syracuse, and I am still researching this periodical!

Starting in 1849, The Charter Oak morphed into The Republican. William Burleigh was still the editor, but not for long, as he headed off to Syracuse later in the year at the behest of the New York State Temperance Society. The first few months of The Republican, though, were edited by William. The pecuniary difficulties that dogged him and his family likely drove the move to Syracuse where a more stable income was likely.

| Newspaper Name | City and State | Full Run Dates | Burleighs Editing | Burleigh Edit Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norwich Republican | Norwich, CT | 1828-1836 | William (apprentice) | 1829 | William Faulkner editor |

| Stonington Phenix | Stonington, CT | 1830-1831 | William (apprentice) | 1830-1831 | Charles Denison, editor |

| We the People and Old Colony Press | Plymouth, MA | 1832-1835 | Charles (assistant) | 1832-1833 | Anti-Masonic |

| The Schenectady Cabinet | Schenectady, NY | 1824-1837 | William (assistant) | 1832-1833 | Isaac and Stephen Riggs, editors |

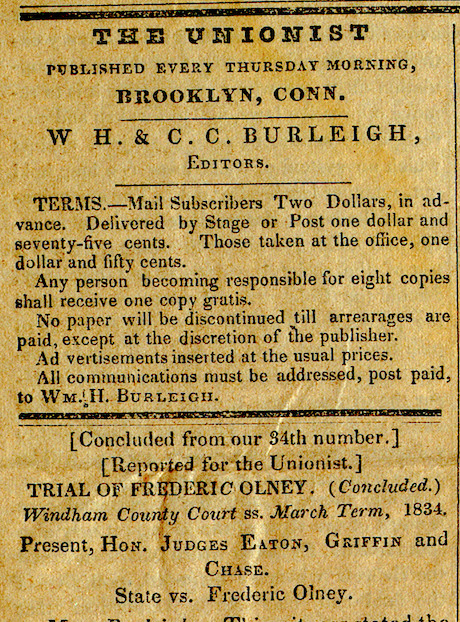

| The Unionist | Brooklyn, CT | 1833-1834 | Charles & William | 1833-1834 | In support of Prudence Crandall |

| The Schenectady Cabinet | Schenectady, NY | 1824-1837 | William (assistant) | 1834-1835 | Isaac and Stephen Riggs, editors |

| The Wreath | Schenectady, NY | 1834-1835 | William | 1834-1835 | changes name to The Literary Journal in 1835 |

| Bridgewater Republican and Old Colony Press | Bridgewater, MA | 1835-1836 | William (co-editor) | 1835-1836 | successor to We the People on which Charles worked |

| The Amaranth and Literary Journal | Bridgewater, MA | 1835-1836 | William | 1835-1836 | successor to The Wreath/The Literary Journal from Schenectady |

| The Liberator | Boston, MA | 1831-1865 | Charles (temporary) | 1835-1836 | Charles filled in during Garrison's many absences after Boston mobbing |

| The National Enquirer and Constitutional Advocate of Universal Liberty | Philadelphia, PA | 1836-1838 | Charles (assisting) | 1837 | Benjamin Lundy's paper, precursor to the Pennsylvania Freeman |

| Christian Witness and Temperance Banner | Pittburgh, PA | 1837-1842 | William | 1837-1842 | William was the principal editor of this organ of the Western Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society |

| The Washington Banner | Allegheny, PA | 1842-1843 | William | 1842 | |

| The Pennsylvania Freeman | Philadelphia, PA | 1838-1855 | Charles & Cyrus | 1838-1855 (intermittent) | Edited mostly by committee; Charles official editor 1840-1842; Charles co-edited the paper with J. Miller McKim in 1844. Cyrus was the official editor from April 1853 to March 1854 when he resigned due to health issues. Both Cyrus and Charles were at times part of the Executive Committee that had oversight of the paper |

| The Voice of Freedom | Montpelier, VT | 1838-1855 | Charles | 1842-1843 | Anti-Slavery paper |

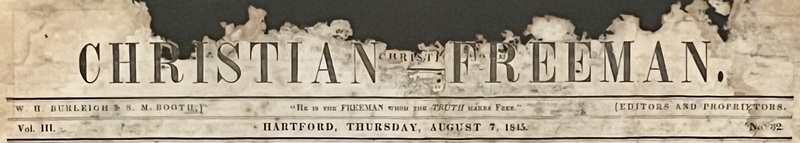

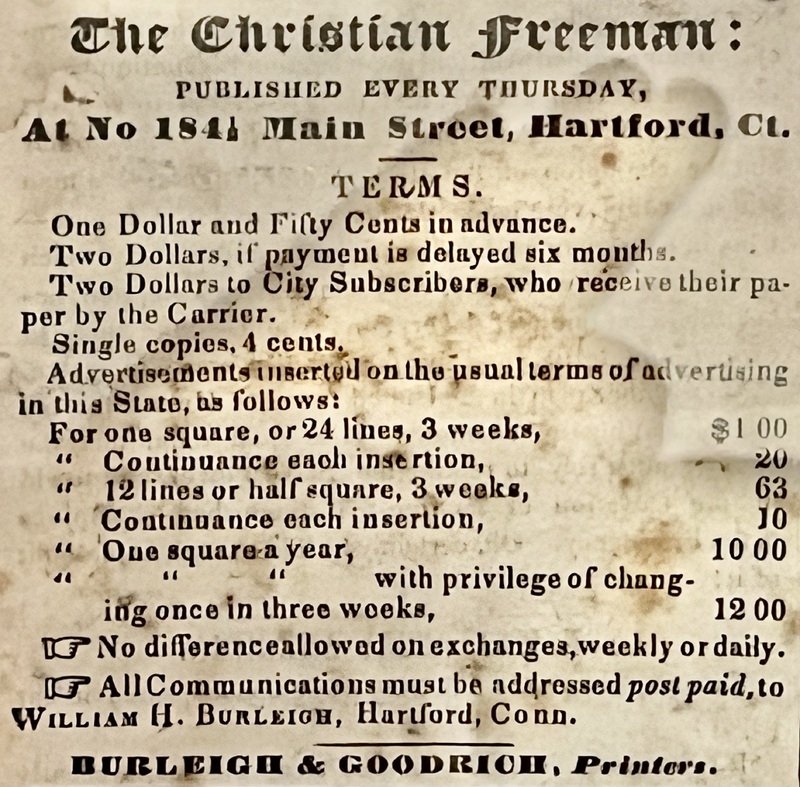

| The Christian Freeman | Hartford, CT | 1843-1845 | William | 1843-1845 | organ of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society |

| The Charter Oak | Hartford, CT | 1846-1848 | William & George | 1846-1848 | Second Series; organ of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society; replaces The Christian Freeman |

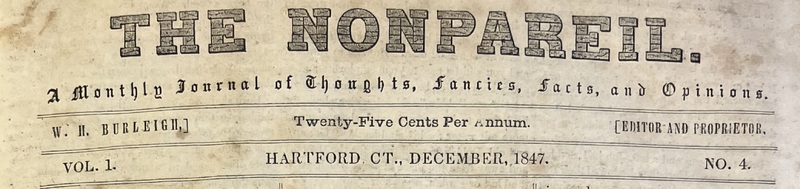

| The Non-Pareil | Hartford, CT | 1847-1848 | William & George | 1847-1848 | Literary periodical |

| The Republican | Hartford, CT | 1849-1856 | William | 1849 | organ of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society; replaces The Charter Oak |

| The Prohibitionist | Albany, NY | 1854-1860 | William | 1854-1855 | an organ of the New York State Temperance Society |

Note: Newspapers that are named in bolded italics are the most significant for understanding the Burleighs.