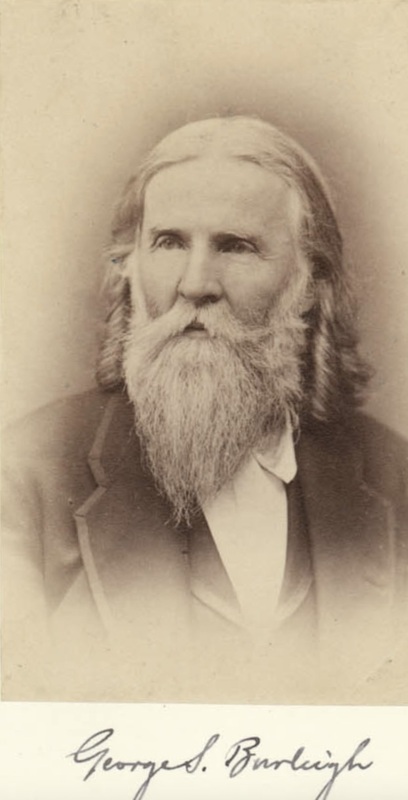

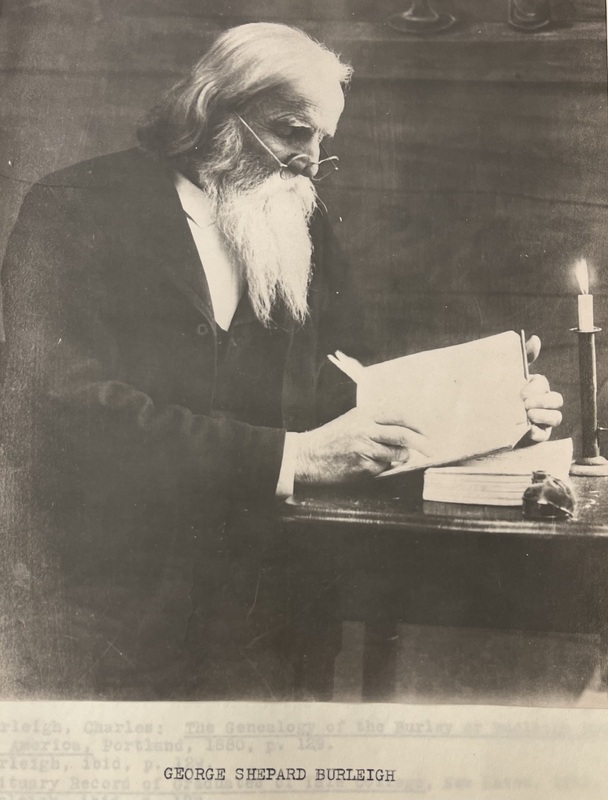

George Shepard Burleigh: Poet of Reform, Nature, and Sentiment

George Shepard Burleigh Basics

b. March 26, 1821, Plainfield, Connecticut

d. July 21, 1903, Providence, Rhode Island

m. Ruth Burgess (1820-1909), March 17, 1849, Newport, Rhode Island

lived in Connecticut and Rhode Island

Silent by voice, but not by pen, George was the genuinely professional writer among the siblings, able to eke out a living from his literary efforts (supplementing his farming).

In the 1840s, with extensive coaching and coaxing from his older brothers - especially Charles and William, with whom he worked directly - George Shepard Burleigh's output reached its aesthetic and political apogee. His editorials were biting and clear-sighted; his stories were sophisticated on issues of gender and race despite their frequently conventional aspects. His poetry was getting widespread attention, and he undertook controversial subject matter, from the impact of the Abolitionist schisms on friendships in his Elegiac Poem on the Death of Nathaniel Peabody Rogers., and the treatment of the mentally ill in "The Maniac". He was noticed by the Transcendentalists, and found many places of publication.

He did not attempt to challenge his elder brothers' on the field of oratory and anti-slavery agitation in public. George was shy and retiring, and as the youngest member of the family, likely intimidated by the national renown and success they had achieved. But the niche he carved for himself in literature actually gave him as large of an audience as the tireless activists in the family.

As befits a poet, George detected the importance of the times in which he was living. Late in his life, at the request of a publisher, he wrote a brief autobiographical statement (in the third person), in which he discloses that when he "was, at length, lured into print, he concealed his personality under various names and initials, contributing stirring lyrics to that mighty struggle for Liberty & Reform, which has made the heart of this century so grand in human history" (George Shepard Burleigh, Autobiographical Sketch, n.d (ca. 1890s), Beinecke Library, Yale University).

George Shepard Burleigh's poetry circulated widely through the nineteenth-century, in some very prestigious locations. Frederick Douglass published his Temperance poem "The Wreckers" in Frederick Douglass' Paper in 1854.

References

Burleigh, George Shepard. "The Wreckers." in Frederick Douglass' Paper (Rochester, NY), December 15, 1854.

George Shepard Burleigh's career as a writer falls roughly into two halves, before and after the Civil War. His later material was largely sentimental and intended for adolescent readers (and their sentimental parents). He wrote considerably less prose after 1865, and almost nothing that had a political theme. There were still pieces that echoed his concerns with spirituality {list a few as they are added}, but the tone and tenor of his output underwent a wholesale change - and not a change for the better - in the latter half of his life. What happened?

My current theories - some of these are semi-humorous...

1) the success of "The Domicile" led him to want to excel in clever word-play.

2) the loss of the only daughter of George and Ruth was traumatic, and led him to increase his focus on the promise of early girlhood

3) the end of the anti-slavery struggle via the horrors of war created too much cognitive dissonance, which he chose to ignore rather than work through (compare to Whitman)

4) he read some of the few poems of Emily Dickinson to meet the light of day and knew, like Thomas Aquinas, that all is work was but straw

5) he shared the Transcendentalist love of the innocence and spiritual seeking of the child, and just went for that with all the vigor and florid filigree of a late Victorian

6) this was the poetry that magazines wanted from him, and he wasn't a wealthy man, so, he wrote this. Yet one would still expect some poems secreted away that represented his own work from his own heart