Anti-Racism: Definitions and Examples

Anti-Racism

An anti-racist person, philosophy, or movement is one that practices the genuine equality of all people in all their capacities. It is much more than the simple defensive denial of saying that one is "not a racist." Anti-racism is an active stance that seeks to dismantle racist policies, actions, histories, and presumptions.

Anti-racism includes acknowledging and renouncing racial bias, intervening to stop racist actions, and, like John Brown, being willing to put one's own safety, even life, on the line to denounce racism. William Lloyd Garrison's rejection of colonizationism in 1829 is a powerful example, as is Lydia Maria Child's recollection that the "Holy Spirit did actually descend upon men and women in tongues of flame" in the early years of the Immediate Abolition movement. Rev. Theodore Wright, Black Presbyterian minister, proves the point when he wrote of white activists that they "must annihilate in their own bosoms the cord of caste" by "looking into at his own heart."

The Burleigh family, in their actions, writings, speeches, travels, and commitments to equality were consistent over many decades. This included publishing Black writings, sharing podiums - and therefore lodging and travel - with Black colleagues, working to understand that to which they had never been exposed - the perspectives of Black Americans. The Burleigh family was not perfect by twenty-first century anti-racist standards. But they were exceptional in their time, which is highlighted by how their whole family embraced the cause.

Anti-racism, as an articulated philosophy, has never been more important than it is now. For white people working to be reliable and courageous allies to people of color, especially in 2025 (when I am writing this), it is a valuable buoy in difficult waters to know that a genuine legacy of anti-racist activists is not only real, but far older than the more famed Civil Rights movement. There has always existed a cognitive minority of white Americans who did not acquiesce to facile cultural lies about racial and ethnic groups. Once these people started speaking out, they attracted others through the compelling nature of their humane and just vision. The Burleighs form an important chapter in such a legacy, because of their bravery in defending and extending the work of the Canterbury Female Academy for Black Women (1833-34), their use of their white skin privilege to protect their African-American colleagues in situations of vigilante violence, and their commitment over the long term of thirty+ years leading to the Civil War.

References

Jennifer Rycenga, Schooling the Nation: The Success of the Canterbury Academy for Black Women. Urbana IL: University of Illinois Press, 2025, p. 42-46.

Theodore Wright, "The Progress of the Antislavery Movement," in Negro Orators and Their Orations, edited by Carter G. Woodson. Washington DC: Assocoiated, 1928. p. 86-92.

Black student from Canterbury Female Academy praises William Henry Burleigh (1834)

The Liberator 4:47:186 (November 22, 1834)

“The following short essay was written by one of Miss Crandall’s juvenile pupils, in reference to the abandonment of her interesting school.”

THE SEPARATION

It was one of the most pleasant sunny mornings of September, when I took leave of my teacher and school-mates. Never, no, never, while memory retains a seat in my breast, shall I forget that trying hour. On the night preceding my departure, while all within was silent as the chamber of death, we were suddenly aroused by a tremendous noise; when, to our surprise, we found that a band of cruel men had rendered our dwelling almost untenantable. The next morning, we were informed by our teacher, that our school would be suspended by the day- that he was going to a neighboring town to see a friend of ours: he accordingly went. In the afternoon, he accordingly returned, accompanied by our friend, who requested that we might be called together. He, with feelings apparently of deep regret, told us we had better go to our homes. With regret, I prepared to leave that pleasant, yet persecuted dwelling, and also my dear school-mates, in whose society I had spent many hours; thankful to my heavenly Parent, that our lot was no worse; yet not without many tears did I return to my distant, solitary home.

There is something, in parting with those we love, from which nature recoils: and when I thought of the distance that would be between us, and contemplated the uncertainty of things, I could but acknowledge the probability of never meeting again in company with my school-mates.

I have found among them simple manners and intelligent minds; and there, if any where, love was without dissimulation. My teacher was ever kind: with him I saw religion, not merely adopted as an empty form, but a living, all-pervading principle of action. He lived like those who seek a better country: nor was his family devotion a cold pile of hypocrisy, on which the fire of God never descends. No, it was a place of communion with heaven. There I have heard the lesson of worldly wisdom, which was my boast at times before I was led to confess that I knew little; and would now sit at the feet of Jesus to be taught of Him. Having Christ for our friend, we need not fear amidst the thickest storms, or in the darkest season, or when enemies beset and foes assail. If all were taught to love their neighbor as themselves, to do to others as they would be done unto, there would be no disposition to repeat the crime of him who slew his brother, and men would abhor to imbrue their hands in the blood of men.”

This remarkable testimony confirms what the Burleigh siblings (Mary, Charles and William) were doing, along with Prudence and Almira Crandall, at the Canterbury Female Academy for Black Women in the brief span of April 1833-September 1834 when the school was operational. This student, bereaved at the loss of her educational opportunities and community fellowship with her sister students, singles out William Burleigh (the only male teacher at the school) for the authenticity of his religion as a lived practice. People often comment on how teachers can be role models - here is a cross-gender and cross-racial example of this practice.

Samuel Cornish endorses the editorial acumen of William Burleigh as "food to the soul" (1838)

The Colored American August 25, 1838 from The Christian Witness

This introductory piece was written by Samuel Cornish, the great minister and editor of Black newspapers. His endorsement of William Burleigh speaks volumes, as he was unafraid to call out racism among white Abolitionists when he detected it. Like William Burleigh, he went with the "New Organization" at the time of the schism. Included here is William Burleigh's first full editorial for The Christian Witness

“Brother Burleigh .

The following noble views, make up brother Burleigh' s "inaugural," to the editor-ship of the "Christian Witness," Pittsburgh, Pa.

We sympathize with every sentiment contained in the address. Such views are food to the soul. We have never expected any thing short of a great "moral warfare" with the combined powers of Satan, of slaveholding interests, of wicked prejudice, and of hypocritical professions. Our liberty and our rights would not be worth having were we to obtain them at a cheaper rate. We are willing to fight for the prize, and it is enough for us to know that God is on our side.”

“TO THE READERS OF THE CHRISTIAN WITNESS.

We need but a brief introduction. We have no time to waste in compliments, nor in promises. Our course, as the future editor of the Witness, must testify for or against us. We bring to our task what talent God has given us, and an entire devotedness to the great cause whose interests we shall labor to advance. Years ago we buckled on the abolition harness, not unmindful of the toil, and persecution, and contumely, and scorn, and peril, which all who would be faithful to the cause of perishing humanity, must be called to endure. - The "great wrath" of the Evil Spirit of Slavery has neither surprised nor intimidated us. The whirlwind of popular violence - the breaking up of the great deep of pro-slavery wrath - the tempest of opprobrium which has beat upon the heads of abolitionists - the agitations and commotions which, like an earthquake, have shaken the land from centre to circumference, have not taken us by surprise. We looked for them all. We look for them yet - and, God strengthening us, we shall be prepared to meet them. The Demon of oppression will struggle desperately ere he surrender his prey. Firmness, and zeal, and self-sacrifice, and gospel prudence, and devotion, and faithfulness unto death, should therefore characterize the friends of holy liberty - the soldiers in this moral warfare. Already has passed upon our cause a baptism of fire and blood. Not vainly hath that blood sent up to Heaven its voice of accusation against our guilty land, nor has the Temple of Freedom, that last great sacrifice upon the alter of slavery, blazed in vain! Every persecution we encounter, every outrage we endure, but renders the cause of humanity dearer to our hearts. Such opposition kindles our zeal, quickens our faith, increases our devotion, and stimulates us to renewed action. Never for a single moment, even in the darkest hour of persecution, have we doubted the issue of this conflict. We are as certain of victory as if it were already ours. We believe that every attribute of Jehovah is pledged to our success. It will most assuredly come. How much of malignity, and wrath, and evil speaking, and insane violence, on the part of our opponents; and toil, and anguish of heart, and despondency, and suffering, on our own, lie between us an ultimate triumph, we cannot tell. Whether any who are now laboring for the redemption of the captive, will live to join in the song of jubilee that shall greet his deliverance from bondage, we know not. Nor need we know, - "Duties are ours - events belong to God." His promises are sure, and His grace is sufficient to sustain us. - As our day is so shall our strength be.

In assuming the editorial charge of the Christian Witness, we feel deeply the responsibilities that rest upon us. The sympathy and cooperation of the friends of the Anti-Slavery cause we have a right to expect. With these faithfully and promptly given, and with the blessing of the Friend of the oppressed upon our labors, this little sheet shall continue to be a "WITNESS" for God and man, against the oppression, and cruelty, and avarice, and meanness of American Slavery.”

This example demonstrates mutual respect between these two editors, and a confidence about William Burleigh's constancy in the movement.

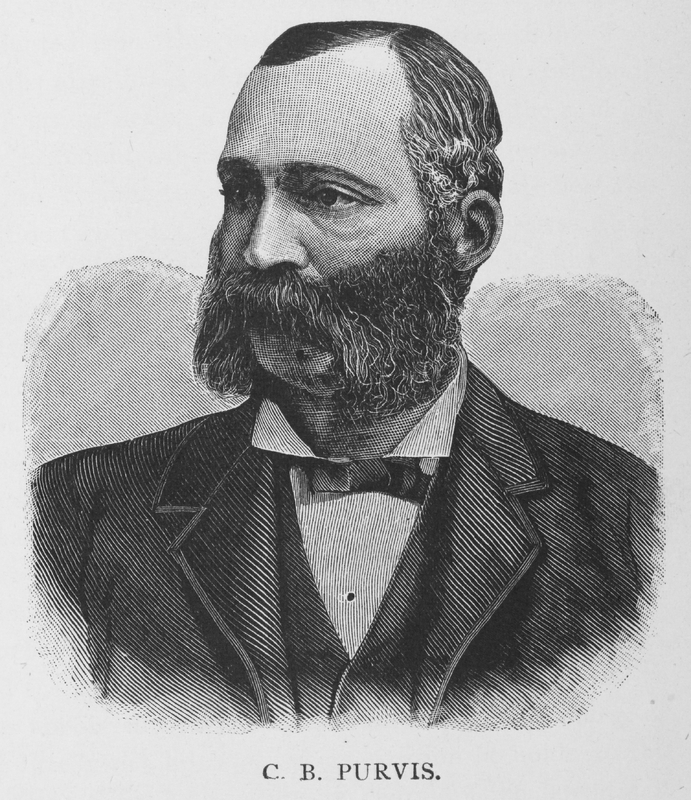

Robert Purvis names his son after Charles Calistus Burleigh (1842)

Philadelphia Black activist Robert Purvis named his son, Charles Burleigh Purvis (1842-1909), after Charles Calistus Burleigh. He went on to considerable fame as a medical doctor, founder of the medical school at Howard University, and one of the attending physicians on President Garfield in the aftermath of the assassination attempt to which he eventually succumbed.

Cyrus Moses Burleigh accompanies a self-liberated woman to safety (ca. 1852)

There was at this time a colored woman named Maria living at C. C. Hood's, who one day, when a slave, heard her master selling her to a slave-trader to go South. Horrified at the prospective change, she lost no time making her escape, and through agencies on the Underground Railroad got to WIlliam Howard's, thence to C. C. Hood's, where she had been living but a week when the Christiana riot occurred. She was the mother of nine children, eight of whom she left in slavery. One, a son, had preceded her, and was living with Moses Whitson. In the following winter he went to Massachusetts. Obtaining employment there by which he could support his mother, he wrote for her to come. Cyrus Burleigh was at that time at Hood's, and proposed, that if she would remain a few weeks until he was ready to return to Massachusetts, near to where her son was living, he would see her safely to the place. She assented, and at the appointed time she met him in Philadelphia, and was taken care of to the end of her journey."

Robert Clemens Smedley. History of the Underground Railroad In Chester And the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1968. Reprint of 1883 edition, Lancaster Pa; Offices of the Journal, p. 82-83.

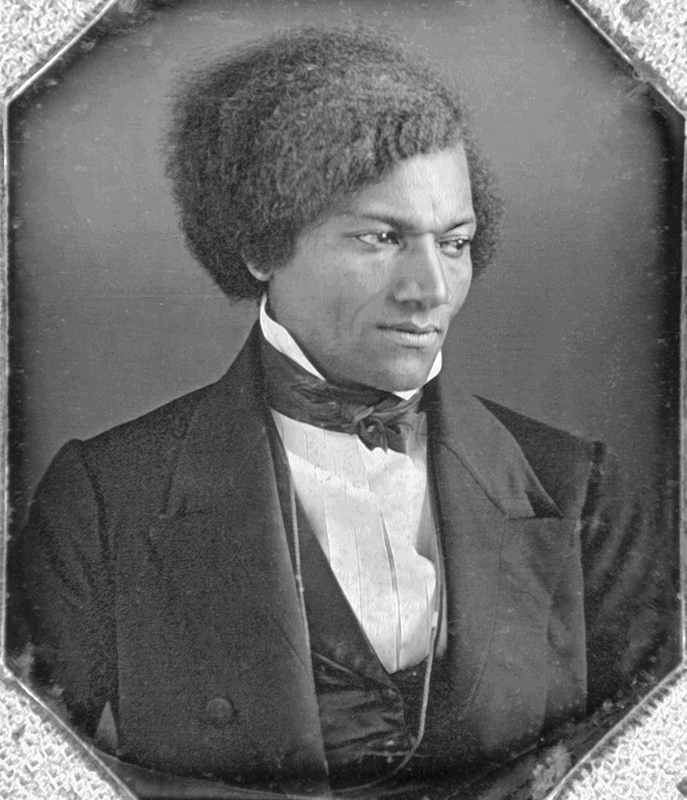

Frederick Douglass's further appreciation of Charles C. Burleigh (1854)

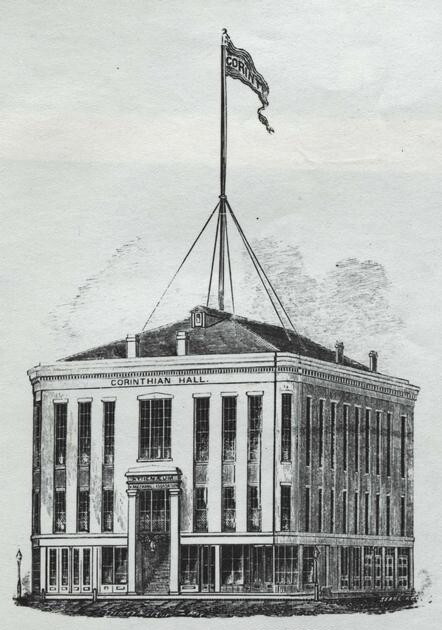

CHARLES C. BURLEIGH. This renowed anti-slavery orator, and indefatigable laborer in the cause of humanity, has been invited to address the literary societies of Oberlin College an honor of which he is well worthy. For among all the advocates of liberty in the United States, we know of none who bring to the advocacy of this cause, a deeper conviction, a more constant zeal, more untiring industry, or a more thrilling eloquence than he. Differing from him vitally, as we do, on some points, we, nevertheless, esteem him and his labors most highly. We doubt not our readers in Rochester, and vicinity, will give his views on the present aspect of the anti-slavery cause, in Corinthian Hall, on Monday evening next. Let Charles Burleigh be greeted by a crowded assemblage, on Monday night. A dozen miles ride from the country, is but a small tax for a moral and intellectual treat so grand as that which may be expected from Mr. Burleigh in Corinthian Hall, on the evening above mentioned.

Frederick Douglass' Paper August 18, 1854 - presumably written by Frederick Douglass (unsigned), concerning a talk scheduled for August 21, 1854 in Rochester, New York.

Charles C. Burleigh Speaks for Black Suffrage, July 4, 1865 (1865)

The 1865 meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in Framingham concluded a tradition: the organization had held meetings every Fourth of July at Framingham's "Harmony Grove" for nearly twenty years. While the search for a complete set of minutes from this meeting continues, the excerpt below reveals much about C. C. Burleigh's understanding of the Black role in winning the Civil War, and the absolute need for Black male suffrage. This excerpt is housed in an editorial that was viscerally hostile to the Abolitionists and to Black rights:

C.C. Burleigh argued that the President had as good a right to give the negroes of the South the right of suffrage as he had to appoint provisional governors, and said “where would you have been had it not been for the black man? The black man helped you to success. In the Book of Decrees you will find it decreed that the flag should never be carried to Richmond and Charleston until black soldiers carried it there.”

Source: Monmouth Democrat (Freehold, New Jersey), July 20, 1865, p. 2.