The Life of an Anti-Slavery Agent

The Burleigh Brothers as Anti-Slavery Agents

Charles, William, and Cyrus each spent years employed as Anti-Slavery Agents - a mission filled with travel, adventure, debates, and the ever-present danger of mobbing and violence. An agent was assigned an area - either a small state, or a county - and visited as many towns as possible where they could lecture. Starting around 1836 (check) these Anti-Slavery Agents included women (all white women at this time), such as Abby Kelley (check name) and the Grimké sisters.

William and Charles were part of the famed Band of Seventy trained in New York City by Theodore Dwight Weld.

The assignments of the Burleigh brothers as agents are not yet fully reconstructed, but correspond to these rough dates and places.

Charles - Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Vermont, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana

William - Connecticut, Pennsylvania

Cyrus - Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania

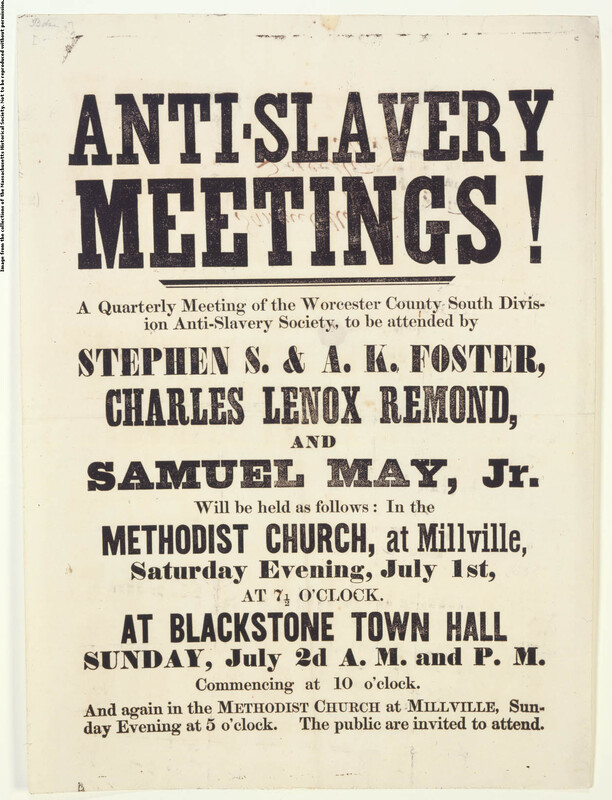

Demands on Anti-Slavery Agents

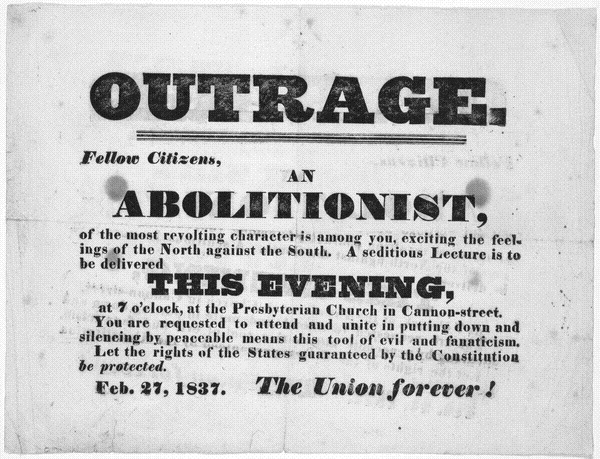

The travel demands on an agent included keeping expenses low (being an agent was definitely not the road to riches). This entailed staying with friends, allies and family along the way. Finding a place to speak was often fraught with partisan gamesmanship - it was not at all unusual to be locked out of a civic center, church, or meeting place that had been legally secured beforehand. Civil authorities were often worried about civil disturbances erupting at anti-slavery meetings - while one can well understand their concern, it was a case of displaced anxiety, since slavery and racism together constituted the greater evil that needed to be confronted.

Another demand was the not unreasonable request by the anti-slavery organizations, that were paying the salaries of the agents, for fre1quent reports. These were also important to the news cycles of the Abolitionist press. As early as 1834, the Agency Committee "Voted that these agents be specially directed to report at short intervals, their labor, success, and expenses."

References

Agency Committee minutes of January 14, 1834 -

Agents Growing and Tending the Abolitionist Networks

The agents - especially in the decade of the 1830s, as the movement for Immediate Abolition was gaining traction - were especially valuable in setting up active networks. This included gaining subscribers to anti-slavery publications, seeding town and county anti-slavery societies, and inviting people of all walks of life - including farmers, merchants, apprentices, and women - to contribute. In this manner, the model based on the early Christian disciples fit well - the agents were eager to include everyone, while the rival American Colonization Society based its appeal primarily to those who were educated and wealthy (due to the daunting logisitics of transporting free blacks out of the country). One can see how the notion of living out both Christian ideals and Christian history could have been used metaphorically. The suffering and miniature martyrdoms only added to the luster.

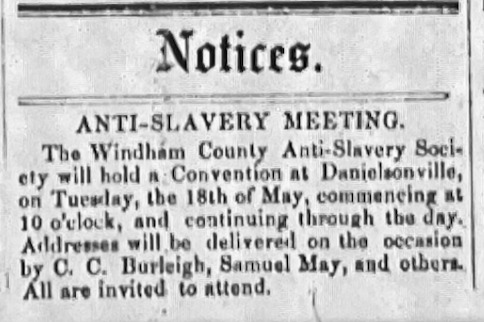

In this paragraph-long summary of less than one month's work by Charles C. Burleigh in Connecticut, the whole gamut is covered: networking, creating new organizations, lecturing, and facing opposition:

He [Charles C. Burleigh] was lecturing in CT during the final three weeks in April. Garrison wrote that Burleigh had been meeting with opposition in Brooklyn a few days before April 16 and had left to deliver an address in Hampton. From April 22 to 25 Burleigh lectured on four successive evenings in Pomfret and formed a society. He delivered an additional address on Sunday, April 24, in Woodstock, about 4 miles away, and followed it by speeches on April 26, 27, and 29. A second society was established. He attended the annual meeting of the Windham County Anti-Slavery Society on Thursday afternoon, April 28. Although he had encountered a mob there the previous month, he lectured in West Woodstock on Saturday, April 30. There he was again met with hooting, shouting, and throwing of books. However, he spoke without disturbance on Sunday afternoon in the same church and in Eastford on Sunday evening. His final lectures on May 2-4, 1836, in towns previously visited were to support the establishment of auxiliaries in Hampton, Pomfret, and Woodstock.

A similar letter, this time from William Henry Burleigh to The Liberator, dates from early 1837. Here we see the continued opposition within Connecticut, and the difficulties faced by agents, who experience "the pouring of rivers of wrath upon [their] head." And yet they persisted. The Burleigh family members would persist in their witness against slavery and racism through the end of the Civil War - almost 30 years after this letter.

The Liberator 4 March 1837

“FROM W.H. BURLEIGH

PLAINFIELD, Ct. Feb. 7th 1837

Dear brother Garrison:

At times, I have been almost discouraged when I have witnessed the apathy, and, too often, something worse than apathy that prevails upon the subject of human rights in Connecticut. I will not tell you the trials that beset me, nor will I trust myself to speak of the opposition of Christians to our cause. God send them a better spirit, and that speedily—or fearful will I be for our country in the day of righteous retribution. The cause is on the advance here slowly. This State is hard ground—but it must be ploughed. Once on the side of Right and it will be as firm as its own rocky hills. But now the spirit of Slavery here is quick and strong, and walled about with a peculiar sanctity — and, he who ventures to lay his hand upon it may look for the pouring of rivers of wrath upon his head. Connecticut is committed in favor of despotism. Her odious ‘Black Law’ has marked her as the yoke-fellow of oppressors. Her clerical gag-law tells too plainly where are the sympathies of too many of those who minister at the altar. These things are discouraging—but do not lead us to despair. The good leaven of Abolition truth is at work here, and it will yet leaven the whole lump. Could the Lecturer have free and easy access to the people, the work would soon be done. But there’s a high wall between him and the people. Who will dare to break it down?

I meet with many encouragements after all. I see continually the omnipotence of truth to subdue passion and prejudice, to overturn error and sin—and my heart is strengthened to go on. The seed scattered here does not indeed spring up so rapidly as in some other places, but a part of it I trust has fallen into good ground, where it will ultimately bring forth a hundred-fold. I have formed no Societies in my route for particular and local reasons, but unless I am misinformed of the state of feeling in places where I have lectured, there is much good material for societies, when the proper time for their organization shall arrive.

Yours for the slave,

W.H. Burleigh

References

Burleigh, William. 1837. Letter to the Editor. The Liberator 4 March 1837, v. 7:10:47.

Myers, John. 1983. Antislavery Agents in Connecticut, 1833-1838. Connecticut History (March 1983), no. 24 p. 11

The Weather and the Roads

When Charles C. Burleigh agreed to a year working as an agent and editor in Vermont, he must have known there would be some vicissitudes due to storms. In a summary narrative about their journey in the northern parts of Vermont in January of 1842, Rowland T. Robinson wrote of how "the badness of the road on the west side of the Mountains has so impeded our progress as to leave very little time unoccupied with travelling or attending meetings among other hazards." The weather, in turn, affects the health of potential attendees at the anti-slavery lectures, and therefore the "audience was as large as the unusual sickliness of the village allowed us to anticipate." Though a rain-storm removed some of the snow from roads, the problems of weather and transportation were not resolved: "We were conveyed from Brandon to Rutland by the kindness of our friends, with wagons, through rain and ever muddy roads, and put up with our warm-hearted friends, Reuben R. Thrall and wife. The weather continuing unfavorable our meeting was not large." And yet, Robinson reports that this meeting was successful and interesting.

References

Robinson, Rowland T., “The Anti-Slavery Conventions,” Vermont Telegraph (Brandon, Vermont), February 2, 1842, p. 2-3.

Dangers Faced by Anti-Slavery Agents

The risks to the Anti-Slavery agents were quite real, but nothing that would have surprised the Burleighs, having endured the persecution they had in Canterbury.

One such incident happened very early in William's time as an agent. This occured in North Stonington, in the far southeastern corner of Connecticut. North Stonington was the home of William's wife Harriet's family, and the very church where his father-in-law was a Deacon was at the epicenter. The event is described in a letter from Latham Hull to Elisha Haley, a well-known Jacksonian politician. Both Hull and Haley were anti-Abolitionist:

"All the news I have to give you is there has been a man at Milltown by the name of Burleigh to deliver abolition lectures. He gave (?) one and appointed another and they shut the door on him and the poor fellow took his flight. They blew the horn and gave him a gun, & he took his flight and has not been seen here since."

To a pacifist like William, the presence of the gun was likely terrifying. One wonders, though, how this incident affected his relation to his father-in-law. Throughout his life, William was chronically short of money to support his growing family. The low pay and high risk of being an Anti-Slavery agent is not the sort of vocation likely to induce the affection of a stern father-in-law watching out for his youngest child!

(Letter, 1836 December 29, North Stonington, Conn., from Latham Hull to Elisha Haley, Washington, D.C., held in the collection of Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. See also Myers, John. 1983. Antislavery Agents in Connecticut, 1833-1838. Connecticut History (March 1983), no. 24 p, 1-28.)

Camaraderie in the Abolitionist Community: A Balm for Tired Agents

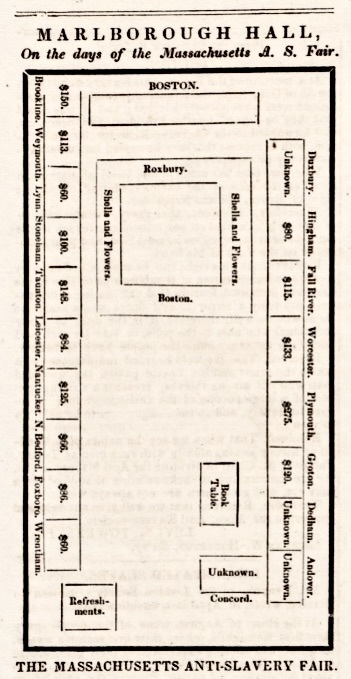

The journals kept by Cyrus Moses Burleigh provide the daily struggles, achievements, joys, and networks in the life of an agent. He describes setting up the hall, and later striking the exhibitions, for Anti-Slavery Fairs, staying with family and friends in his travels, attending an anti-slavery picnic, and in general conveying the camaraderie that developed.

A Busy Season for Charles C. Burleigh

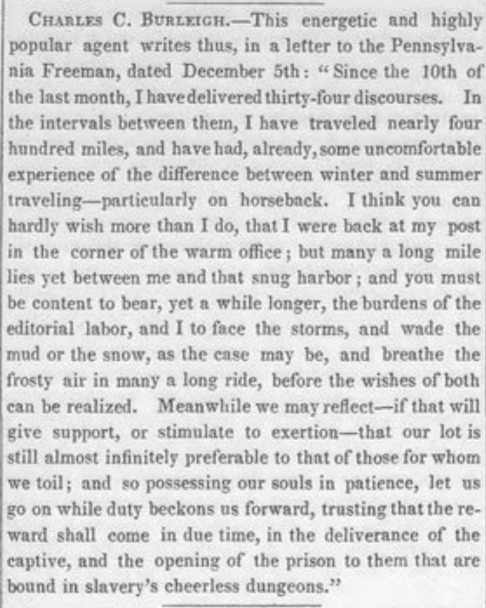

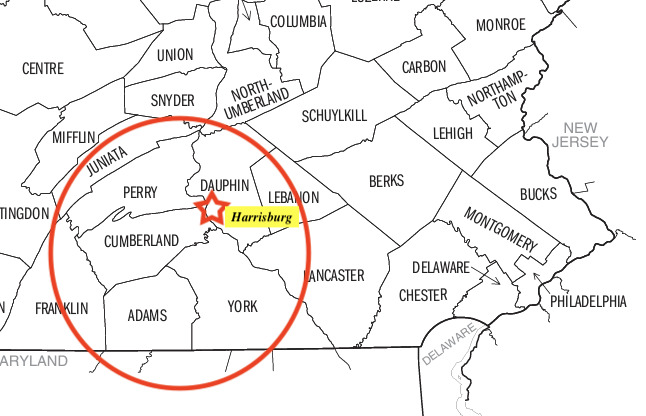

In a letter to The Pennsylvania Freeman just prior to when he assumed its editorship, Charles C. Burleigh provided a remarkable compendium of his debates and presentations between December of 1839 and March of 1840. This single paragraph dealing with his time in central Pennsylvania that winter gives abundant testimony to his energy!

On the 7th [of Janaury 1840] I came within the limits of my intended field of operation for the remainder of the winter, by reaching Harrisburg, which has been a sort of central point to my subsequent movements. I have since lectured seventy-one times, including two addresses particularly to the colored people, three on the subject of Peace, and four on that of Temperance. My labors have been distributed over five counties. I have spoken eighteen times in Dauphin, at four different places; in Adams twelve times, at five places; twenty-four times in York, at eight places, and at two places in Perry, six times. In some I have lectured but once, in others, two, three or four times, going over as much of the ground as the time would allow, and circumstances seemed to demand—while in yet others I have given a protracted course. In the borough of York for instance, I presented in twelve lectures, a pretty full view of the prominent points of the subject;—the character and tendency of slavery; (with a refutation of the attempted scripture argument in its defence,) the duty and expediency of immediate emancipation; the inadequacy of all schemes of gradualism, (including colonization,) to do justice to the slave or promote the real interest of the master or the country; the plan and measures by which we seek to effect our object; and our reasons for anticipating ultimate success. In Harrisburg I gave a similar course of the same number of letures—varying, however, in some aspects, in the manner of treating the subject, and in some of the topics discussed. In Gettysburg I gave five, covering only a part of the ground. I may visit that place again, but it is uncertain.

References

Charles Calistus Burleigh. "Letter to the Pennsylvania Freeman." Pennsylvania Freeman 6:30:3 (April 2, 1840).