Agency and Activity in the 1830s

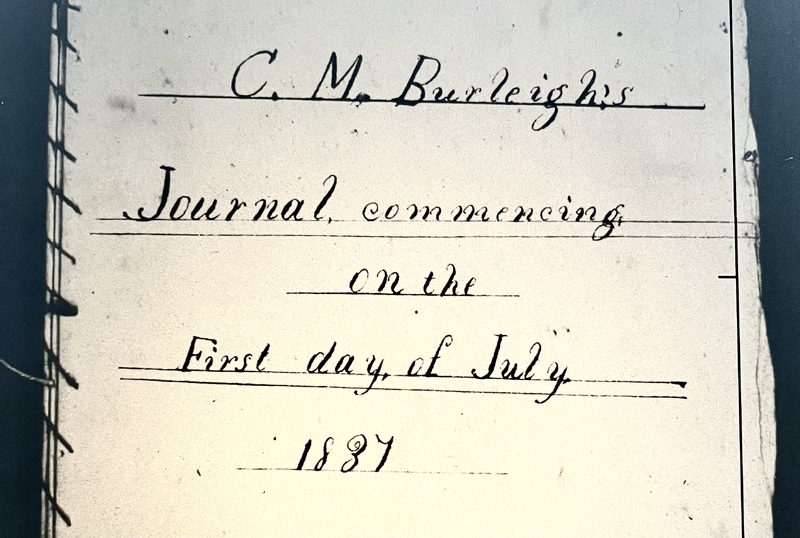

When the Canterbury Female Academy for Black Women closed after a vicious nighttime attack against the school in September 1834, the Abolitionist energies of the Burleigh family took on new forms. William moved to Schenectady to escape the wrath and writs of the Canterbury bullies, while Charles went to Boston to assist Garrison in the offices of The Liberator. Mary continued her work in the Brooklyn Female Anti-Slavery Society. Meanwhile, the younger brothers were maturing. By the end of the 1830s Cyrus Moses Burleigh was keeping a journal, and George Shepard Burleigh was carefully collecting his earliest poetic materials. These two documents are currently in process of being transcribed, and will be made available on this website, hopefully by the end of 2024.

William was the first of the siblings to enter into marriage, when he wed Harriet Frink in Stonington, Connecticut in December of 1834. The couple returned to Schenectady, but then, perhaps missing family or wanting better opportunities for literary publishing, they had moved to Massachusetts by the early months of 1836.

Charles' life in the immediate aftermath of Canterbury was quite exciting, and frankly dangerous. Having imbibed peace principles from the likes of the Windham County Peace Society, the writings of Jonathan Dymond, and his witnessing the behavior of Crandall and her Black students, Charles became one of the most "mobbed" lecturers on the Abolitionist circuit - and he never struck back with violence. The most notable example of this is the role he played in rescuing William Lloyd Garrison from a mob in October 1835.

Charles and William were both a part of the famed group of early anti-slavery lecturers known as "The Seventy." Trained by Theodore Dwight Weld - another Windham county native - these lecturers specifically modeled themselves on the seventy disciples of Jesus, meaning to spread the anti-slavery message as a natural extension of Christianity and 'christian' behavior. They endured much in terms of mobbing, harassment, and threats, as documented on this website's page about Antislavery agents. Charles, in particular, because of his unconventional approach to coiffure and clothing, was an easy target for both the infuriate and the roguish tormentors of agents.

John moved to Massachusetts, albeit in a region along the same riverine corridor as Plainfield. He married Evelina Moore in 1837. Both John and Evelina were participants in anti-slavery organizations, though they were not high-profile members or officers. (reference). We know that Mary Burleigh visited them, from reports in letters and Cyrus's journal.

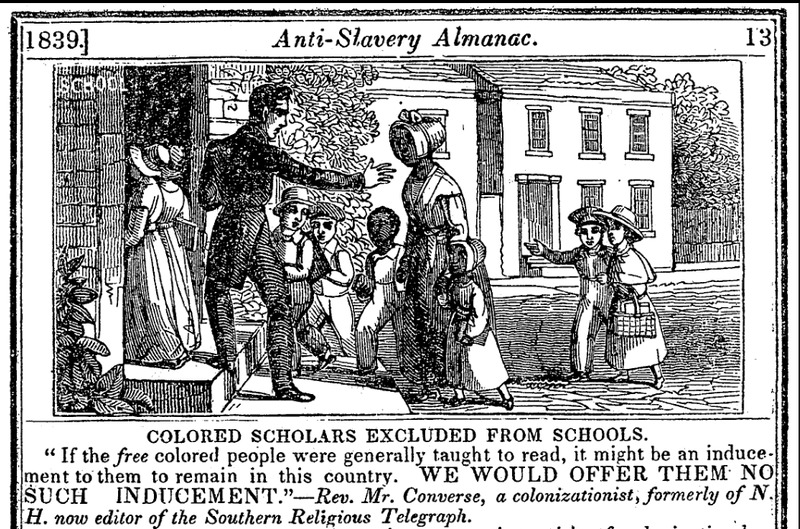

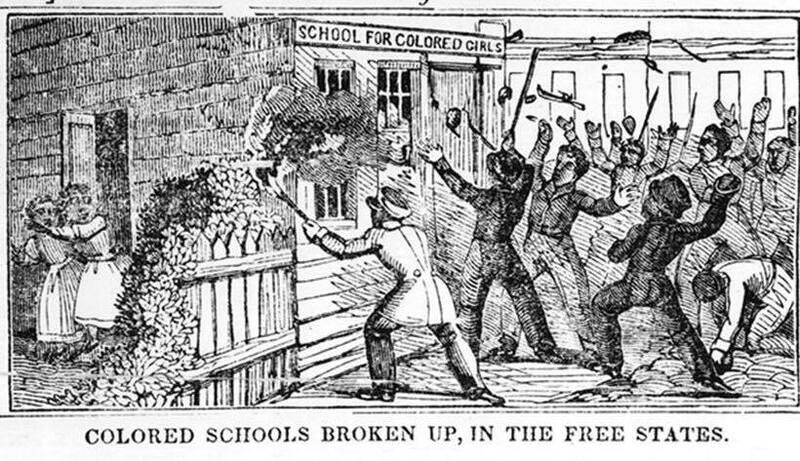

The younger siblings - Lucian, Cyrus and George, along with their sister Mary - remained in Plainfield at the family home for much of the decade. The first two volumes of Cyrus's diary pulls the curtain back on much of their daily lives - farming routines, church services, visits from friends, neighbors and family, debate societies, attending school (in a very irregular manner), and attending anti-slavery and temperance meetings. One of the highlights of any given day would include a trip to the post office. For instance, on August 22, 1838, Cyrus received the 1839 Anti-Slavery Almanac published by the American Anti-Slavery Society. This particular edition contains two pictures about northern resistance to education for African-Americans, that must have immediately brought the Canterbury Female Academy to the minds of the Plainfield stalwarts.

References

Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1839 - online version provided by Cornell University

Cyrus Moses Burleigh, Diary, entry of August 22, 1838.

The daily life of running the family farm in Plainfield charts regular seasonal rhythms, and reveals a perpetually anxious eye on the weather. And as anyone who has spent time in Connecticut knows, there is a lot of discussion of clearing stones from fields. There is a reality behind the stone fences that dot the Nutmeg State!

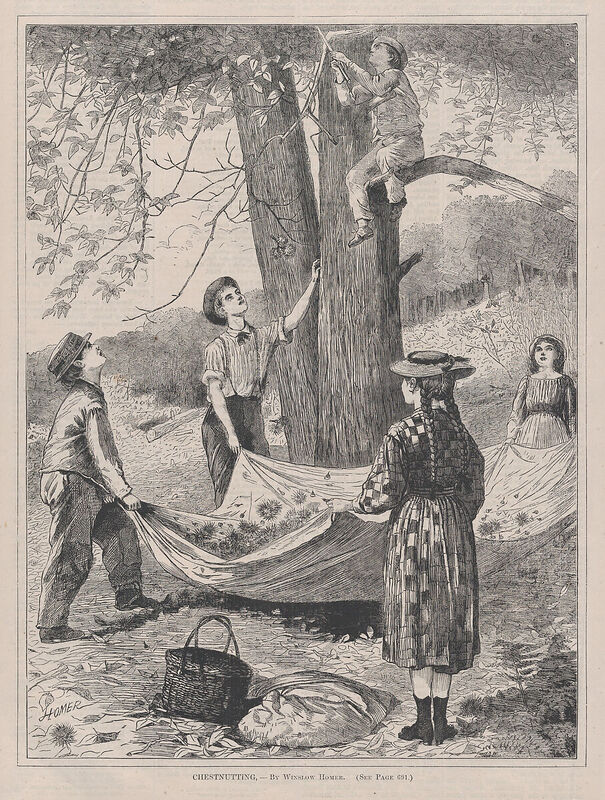

In his journal, Cyrus speaks of a fall ritual, where "we all went chestnutting in the evening." This storied New England and Applachian tradition involved shaking the tree to induce the burrs that hold the chestnuts to fall out. Winslow Homer's nostalgic 1870 illustration of the practice mirrors what Cyrus described in his journal, and what George had written in a similarly nostalgic poem the previous year, 1869