Ruth Burgess Burleigh: Abolitionist and Poetic Partner to George

Ruth Burgess Burleigh Basics

b. October 1, 1820, Little Compton, Rhode Island

d. March 11, 1909, Providence, Rhode Island

m. George Burleigh (1821-1903), March 17, 1849, Newport, Rhode Island

lived in Rhode Island and Connecticut

I. Early Life and Schooling

A poet, writer, and abolitionist, Ruth Burgess Burleigh was not nearly as visible or well-known as her extended family. Yet her deep devotion to the Burleighs as well as her own family and the causes they supported are clear from the records we do have about this remarkable woman.

Ruth Burgess was born on October 1, 1820, in the small town of Little Compton, Rhode Island. Her parents, Deacon Thomas Burgess and Ruth Richmond, were both widowed when they married in 1820, with her mother having five children from her previous marriage, and Thomas likely having serveral of his own as well. According to Ruth’s daughter-in-law Sarah, the blended family “were very happy together, and held most cordial relations all their lives.”

Ruth was educated starting at the age of three or four at “the old peaked top school-house” in Little Compton, a one room school that seems to have taught students of all ages. She later wrote about her experience there in an essay titled “School Days at the Commons and Peaked Top,” with commentary on her teacher, class activities, and what material students were expected to learn. Some of her memories include that:

-

[When she first started at the school, the teacher] only required me to “say my letters” four times a day. An incident connected with this branch of my education, which I was too young to remember has been often repeated by my elder sisters. It seems that I was held rigidly to my daily duty at the alphabet. One day I could not remember the name of a letter which Miss Betsey was confident that I had once learned. As I failed to recall it she threatened to hang me up to the pole, and was proceeding to take off her long, knit garter for a noose when something intervened to prevent the execution. Perhaps the terrible emergency inspired one to recollection.

-

Reading, writing and spelling were the only sciences taught in the summer school at that time, I think.

-

The “reading books” followed the primer in a remarkable order. The “New Testament” came first the “English Reader,” which was followed by a “Sequel.” Why the “Testament” should have succeeded the primer as the first “reading book,” is a mystery, as there are more unfamiliar words, and more words difficult of pronunciation in that look than in any other class-book used in school.

-

The only trial within my recollection under Miss Betsey’s rule, was in learning to sew patchwork “over and over.” After much painstaking effort, and some pride in the very seam resulting therefrom it was hard to have ones work recognized by Miss Betsey – to be told that it was “all fused up to a leetle” “stitches a ridin over one another” – and then to be obliged to work longer in picking out these stitches, than in toiling to put them in.

-

I remember no difficulties with lessons, only that “Murray’s Grammar,” and “Daboll’s Arithmetic,” were utterly incomprehensible to me, and were never explained. I did not know why we “carried one for every ten,” in “doing our sums” until I had “ciphered” for years.

-

After [the resignation of one disliked schoolmaster] came better teachers and improved text-books. We discovered the meaning of our lessons, and learned that our teachers could be our friends.

Although there is little information available about Ruth's early life, this essay in particular provides remarkable insight into her education and early childhood. According to her daughter-in-law Sarah, she later "attended the Select School established by Deacon Isaac Richmond (a cousin of her mother’s) in a building next his own home on South of the Commons Road." Unfortunately, there is very little surviving documentation about this school.

II. The Burgess Family

While Ruth's marriage to George certainly would have exposed her to the family's political and activist sentiments, these causes would not have been new to her. The Burgess family, particuarly Ruth's father Thomas, were also staunch anti-slavery advocates. Like much of Ruth's life, her family's activities are much less documented than that of her in-laws, but there is historical evidence that suggests the Burgess home in Little Compton was an Underground Railroad stop. If this is true it demonstrates that Thomas Burgess was committed to anti-slavery not just through words, but was also directly taking action in fighting against the practice. Additionally, the Burgess family opening thier home to escaped slaves might have put a young Ruth in direct contact with individuals who had suffered the horrors of slavery firsthand; no doubt increasing her individual sentiments against it. At the very least, the Burgess family's commitment to anti-slavery was instilled in Ruth prior to her marriage to George.

Another example of the Burgess family's commitment to anti-slavery comes from an 1843 "come-outer" incident in Little Compton. The come-outer movement was a form of political activism in which members of an established organization such as a church would leave that institution in protest of their views. The term was originally used to described Christians who left their churches due to opposing views on slavery.

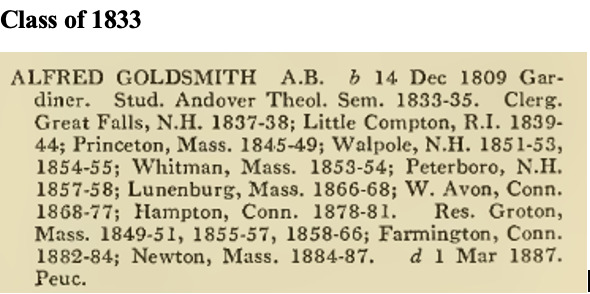

This was the case in Little Compton, when in 1843 Deacon Thomas Burgess led sixteen members of the Congregational Church of Little Compton in "coming out." The inciting incident in this case was when the Rev. Alfred Goldsmith refused to preach against anti-slavery. Records suggest that in addition to Thomas leaving the congregation, Ruth was one of the sixteen members who seceeded as well; she would have been 22 or 23 at the time, and several years away from meeting her future husband. The seceding members formed their own Congregational Church and passed a resolution against enslavement, but rejoined their former institution after Rev. Goldsmith resigned under pressure. This incident might have demonstrated to Ruth the value of political activism, but also emphasizes her own family's commitment to ending slavery.

Thomas Burgess passed away in 1845, two years after the come-outer event. It's unclear if he and George ever met, but one can only assume that he would have approved of Ruth's marriage to someone as staunchly committed to anti-slavery ideals as he had been, and proud of her lifelong commitment to social equality.

III. Marriage to George and Relationship with the Burleighs

With George and Ruth's similar interests in literature and devotion to reform causes, its no wonder the two hit it off. According to Minnie Spies' 1934 thesis on George, the two met in 1849 while George wsa lecturing in Little Compton. However, Spies also states that "Her father, Thomas Burgess, who was the representative of the underground railway system there, entertained the young abolitionist in his home" – a fact that cannot be true given the substantial historical records stating that Thomas died in 1845. Spies' timeline is thrown into further question by a diary entry from Cyrus Burleigh, who wrote on September 6, 1844 that "Geo & Ruth Burgess returned to Pawtucket this evening intending to go to Little Compton tomorrow" – suggesting that the two were acquainted for several years prior to their marriage in 1849. Cryus' entry also implies that George and Ruth were traveling together while not married, which would have been rather scandalous for the time. Cryus seems to be a more reliable source of information, but is unfortunately lacking in specifics about how and when George and Ruth met, or what their courtship was like.

Regardless of the specifics of their meeting, however, George and Ruth married on March 17, 1849, when he was 27 and she was 28. Spies' thesis states that the two moved to Plainfield, CT after marriage, although they also lived in Little Compton and Providence RI, and possibly in Vermont at other points during their marriage.

According to the 1850 census, which was taken on July 27, 1850, George and Ruth were living in Plainfield at that time with their daughter Lillian, whose age was given as two months old. Unfortunately, records about Lillian are very scant, as she passed as an infant. Spies listed her death as taking place in July 1852, and Lydia Burleigh speaks of wanting to see her in a letter to Ruth written in Feburary of that year. Likely, Lillie died sometime in either 1852 or 1853, a loss that is certainly reflected in George's writings, and likely had a profound impact on the whole family.

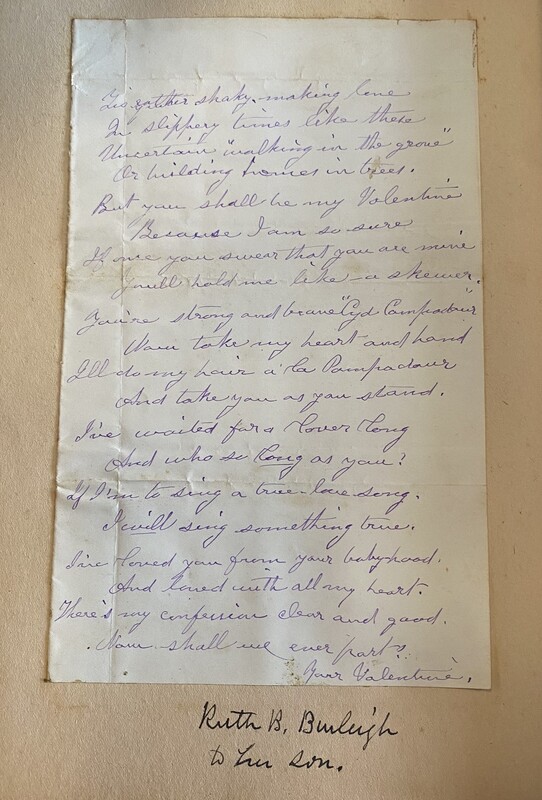

The couple had only one other child, a son Sydney Richmond Burleigh, who was born on July 6 or 7, 1853. Sydney became an artist of some note in Rhode Island, and seems to have remained close to his parents throughout his lifetime. His wife Sarah saved and compiled many of George and Ruth's writings, and wrote that George and Ruth spent winters in Providence with Sydney during the latter parts of their lives. Ruth's love for her son in particular, can be seen in an undated poem she wrote for him signed "Your Valentine."

In addition to her immediate family, letters between Ruth and different members of the Burleigh family shows a closeness between them. A letter that Charles' wife Gertrude wrote to Ruth on Feburary 6, 1850, for example, includes the lines:

Where is thee now with darling little Lillie it seems a long while since we parted even now, & it wo'd give me joy to see your dear faces now – Can I stay three months? That too must be left to the future to decide – but I mean to stay!

Other lines in the letter suggest that Gertrude was familiar with Ruth's Little Compton friends, perhaps meaning that she had visited before, or that Ruth had discussed her relationships with Gertrude in the past.

A letter that Charles wrote to Ruth was penned on March 16, 1856, and suggests the two had a regular correspondence:

Sister, dear, Thy right welcome letter of the 3d & 10th inst., reached me yesterday afternoon, & would have done so two days earlier, had I not been off upon a short excursion which kept me from Sunnyside for three days. Glad was I to hear from you all and more, for I had been wondering a good while why no word came from you. I am sorry to hear of the illness of thy sister & her child, but hope that both may be well again ere this.

Charles also expresses his desire to visit in the same letter, writing:

Give [Rickie, assumedly a nickanme for Sydney] Uncle Charles’ kiss & blessing, & tell him I mean to come & see him some day, if nothing happens to hinder. As for my little ones, I hear good news of them from their mother, & I doubt not they would be right glad to see Aunt Ruth & Uncle George & cousin Rickie, but when they will, unless you come to where they are, it is not easy to say.

Finally, in addition to the Burleigh siblings, Ruth also appears to have exchanged letters regularly with the matriarch Lydia. One letter she wrote to Ruth on Feburary 12, 1852, read:

Dear Daughter Ruth

I received a note from you by George for which I was very glad. It seems a long time since I saw you but I suppose what has been our loss has been your mothers gain...

Your father [Rinaldo] says give my love to Ruth & Lillie too you must give the little one a kiss for us all

I don’t see how you are to get her home till the weather is warmer Mary sends love to you both. Give my love to your mother

I should be glad if she could be well enough to come & see us after you come home Though we live in a changing world I hope you will be preserved & returned to us in safety

I hope you will write after if it is but a little It is not so much trouble for you young people to write as it is for me with my trembling hand. Remember me to your young friends Kate as you call her (I don’t recollect her other name) & Mary Wilber

I am your affectionate Mother

Lydia Burleigh

As these letters suggest, Ruth seems to have shared a close relationship with her in-laws, although distance seems to have kept them from seeing each other in person very often. They seemed to be familiar with each other's families and friends, and seem to have frequently exchanged letters. Perhaps one of the clearest indicators of the Burleighs's feelings towards Ruth, however, was in a letter Cryus sent to George on March 26, 1845. Although he begins the letter by commenting on it being George's birthday, Cryus then writes:

I came into the city a day or two since, & found a brief letter from Ruth that though it came from the past was a voice from the infinite & spake from the lofty heights of the future as clear as the tones of prophecy. I love to listen to the musical notes of her spirit; they come to me as the spirits harmony gliding over the smooth waters of Truth.

We can't be certain if Cyrus was referring to Ruth Burgess here or if he was speaking of another unknown Ruth, but given that we know from Cyrus' diary that George and Ruth were traveling together in the fall of 1844, it seems distinctly possible that the two had met before and she was the subject of this high praise.

Although George and Ruth's living in Little Compton and Lydia's remarks about Mrs. Burgess imply that Ruth remained close with her own family, it also seems clear that she was beloved by the Burleighs as well. Ruth, with her passion for social equity, art, and literature, fit right in with her extended family.

IV. Poetry and Writings

Throughout her entire life, Ruth maintained a strong interest in literature as both a reader and a writer. According to her daughter-in-law Sarah, she was a member of a Literary Society in Little Compton prior to her marriage, and also "one of the founders of the Library that for years supplied reading matter to the country farms." Later, when she and George were living in New York City, she was an early member of the woman's club Sorosis, a professional group that was interested in art, literature, science and other related fields. Sorosis also had a familial connection to Ruth, in that William's wife Celia was one of its founding members. In additon to being a member, an article from The Revolution, a newspaper founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, reported in March 1871 that one of Ruth's own poems was read at a Sorosis meeting; an honor that stresses her literary talent. The John Hay Library at Brown University also has a copy of an undated letter Ruth sent to the group from Little Compton, which speaks to some of her interests and beliefs regarding women's equality:

To Sorosis –

It is with a little feeling of shyness that I step aside from my busy home-life to come before an association of women so nobly gifted and so highly cultivated as Sorosis.

But fancying myself partly concealed by the veil of invisibility in which one may appear, when making a speech through the pen, I take courage to show my interest in your proceedings, and my desire for your success, in the only way practicable for me.

In my little “cottage by the sea”, I have found it pleasant to be associated in name, with a society of women who can be great enough to forget all small personal vanities and ambitions, that they may work advantageously together, for the improvement of our sex in art and science.

From my earliest consciousness I was a lover of Beauty, and in the days of my youth I was ready to bow my soul in adoration, to the artist, and follow in the footsteps of Science, whithersoever she might lead me. Untoward circumstances impeded my progress in science, and though they could not conquer that love of the beautiful which was implanted in my nature, they, yet, hindered its expression.

Therefore, I hailed with delight the formation of a society of women banded together to help each other, in the attainment of their aspirations towards Beauty and Wisdom.

Women, in the walks of science and art, need every aid which they can render to each other, the more, because these paths are made harder for them than for men, by the very laws and customs which have made our feet more tender.

But, if we are only loyal to each other and to our own highest ideals, we may walk right royally over every obstacle which folly and ignorance have placed in the way of our progress.

We want more liberal views[?], higher aims, a stricter loyalty to each other and to the highest, largest truth which we are able to recognize; and, to this end we want freedom.

It is a well recognized fact, in the philosophy of Governments, that a subject nation can make little or no progress in the higher branches of art and science. Is not this a significant fact, which woman would do well to consider?

If we were enfranchised from those legal, political, and social disabilities, under which we lie today, what might we not be and achieve?

How many of us feel these burdens repressing our aspirations, hindering our full development, and shaming our bright ideals!

It is true, that, were these disabilities of law and custom removed, circumstances would not permit us all to follow a career of art or science, technically so called. Nor is this desirable for, or desired by, all. But these might of allow such a career who were fitted for it by nature.

Years have taught me to separate the artist from his work. Genius is an inspiration of the gods, who lift the sculptor, the painter, or the poet, up from the sphere of poor human frailty for a time, while they use his hands to fashion some beneficient “thing of beauty” to bestow upon the world. This accomplished, the artist too often falls back, even below common living. Alas, that doing divine work should ot make man divine! — that an artist may give a sublime ideal to the world and fail to live it! A noble and harmonious life is a constant exponent of the divine within us, and one may, perhaps, fashion, of his own nature a work of more beauty and more beneficent to the world, than sculptor’s chisel poet’s pen, or painter’s brush has ever accomplished, and in any circumstances the inner life may become beautiful if permeated by a noble thought. But for a full development of all the faculties of our being, and the accomplishment of our best doing we need above all things else, freedom. It is said that woman will always be enslaved by her affections. Why should this be? We would not lose a tithe of that power of loving in the bestowal of which God has honored us beyond the stronger sex. He has denied to them the boon of Motherhood. [sic]

But our love should not be a blind idolatry — the slavish love of a dog for its master, or the unreasoning instinct of a hen, which leads her to protect and cherish her brood. Toward her husband, it should be the intelligent love of a human being for an equal, and toward her children, a protecting, helpful, but sensible affection. Such love is no slavery.

Is there any reason why self-sacrifice should be considered a virtue to be required of woman only.

But any woman will say that it requires more heroism to live out her convictions of right, and follow her highest ideal, than any amount of self-sacrifice can call for.

If we can but learn to respect ourselves as simple human beings, and if we may but be allowed to live out our whole true natures, under no restrictions but such as God and Nature have set for our limits, our lives shall be nobler, and the world shall be better for our living.

Yours for this higher life,

R.B. Burleigh

This letter is a remarkable look into Ruth's viewpoints on the subject of women's equality, and stresses how integral social equality was to her beliefs. These themes can also be found in her poetry and other creative endeavors, but this letter as well as Ruth's involvment in Sorosis stresses just how important the cause was to her.

Being involved with Sorosis was an opporunity for Ruth to lean into her political beliefs, but also for her to engage with literature. Stories from her family suggest that literature was a lifelong passion of Ruth's – her daughter-in-law Sarah wrote that towards the end of her life, Ruth's "memory failed but never for books, and when lying helpless in the dark would with her attendant repeat passages from Her favorites of Dickens." Sarah paints here a sad picture of Ruth's final days, but also of the clear importance literature and writing held for her through the end of her life.

In addition to a love of reading, Ruth was also an acomplished author of poems and short stories. She never achieved the literary fame of her husband, but some of her works were published in newspapers, and handwritten copies of her writings were preserved in scrapbooks by Sarah.

Much of Ruth's writings focused on the world around her. The two short stories we have of hers, "Pussy's door-bell" and "Elsie's Sacrifice," both center around slightly fantastical yet believeable scenarios: a cat who taught himself to use a vine as a doorbell, and a girl who gave her favorite doll as an offering to God in order to summon a much-needed rainstorm. It's not clear if she wrote either of these stories based on personal experiences or tales she heard, but both feel like situations that could have happened in the world of Little Compton or Providence.

Ruth's surviving poetry, meanwhile, explores themes such as love, tribute, and activism. One untitled poem preserved by Sarah is signed "your Valentine," and includes a note that it was written from Ruth to her son, Sidney. Sarah also saved a large sheet with three separate poems on it; one uncredited, and one each by George and Ruth. The three works all appear to be a tribute to a Little Compton woman named Lydia, and its collaborative nature speaks to the intellectual bond that George and Ruth shared. Ruth also penned a tribute to Edgar Allan Poe in 1874, and another work titled "Ave Maria" in the 1850s that also reads as an ode to someone who has passed.

One of Ruth's most impressive works, however, is a poem titled "Woman," which was published in at least two newspapers. This piece focuses on the right of women "to stand, a peer, among the noblemen of earth," and states that women of the world will no longer see themselves as lesser than men. This work hints at another cause Ruth was deeply intersted in advancing - women's rights - and its publication speaks not only to its literary merit but also to how the sentiments she expressed in it were shared by her peers.

Although she was never as well-known as her extended family, Ruth Burgess Burleigh was clearly a woman who was passionate about many of the same subjects as they were: social equality for women and Black Americans, literary pursuits, and family. While many of the finer details of her life have been lost to time, the ones we do have paint a clear picture of a remarkable woman who was in every way, an equal of the Burleighs.

References

-

Burleigh, Charles to Burleigh, Ruth, 16 March, 1856. 1998.13.97 Historic Northampton, Northampton, MA.

-

Burleigh, Cyrus to Burleigh, George, 26 March 1845. HA1228. John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, RI.

-

Burleigh, Cyrus. “Journal of the Little Things of Life,” page 38. Charles C. Burleigh papers, 1844-1859 – Am.8192 Box 1. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

-

Burleigh, George Shepard and Ruth Burgess Burleigh. “Poems by George S. Burleigh and Ruth B. Burleigh.” Box A47.4. Little Compton Historical Society, Little Compton, RI.

-

Burleigh, Getrude to Burliegh, Ruth, 06 February 1850. 1998.13.98. Historic Northampton, Northampton, MA.

-

Burleigh, Lydia to Burleigh, Ruth 12 February 1852. 1998.13.215 Historic Northampton, Northampton, MA.

-

Burleigh, Ruth Burgess. "Sorosis Letter." Undated. HA 1181. John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, RI.

- Burleigh, Ruth Burgess. “School Days at the Commons and Peaked Top.” Box A71.8, 1976.09: “School Days at the Commons.” Little Compton Historical Society, Little Compton, RI.

-

Cleaveland, Nehemiah . History of Bowdoin College and Biographical Sketches of the Graduates from 1808 to 1870, inclusive. Edited and completed by Alpheus Spring Packard. Boston: James Ripley Osgood & Company, 1882

- Rhode Island Historical Society.”Petition for Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law from the ‘colored citizens’ of Newport.” EnCompass: A Digital Sourcebook of Rhode Island History. Petition for Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law from the “colored citizens” of Newport | EnCompass

-

Spies, Minnie Lee, George Shepard Burleigh. Masters’ Thesis, Department of English, Brown University, 1934.

-

The United Congregational Church of Little Compton, Rhode Island. “Local Church Profile for Churches Seeking an Interim Pastor.” 2023. Page 4. UCC Little Compton IN Profile 11-2023.pdf

-

U. S. Census Bureau; 1850 United States Federal Census, Plainfield, Windham County, Connecticut, “Lillian Burleigh.” Accessed via Ancestry Library.