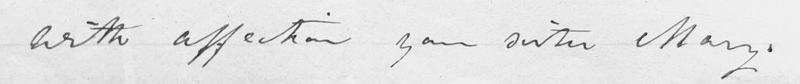

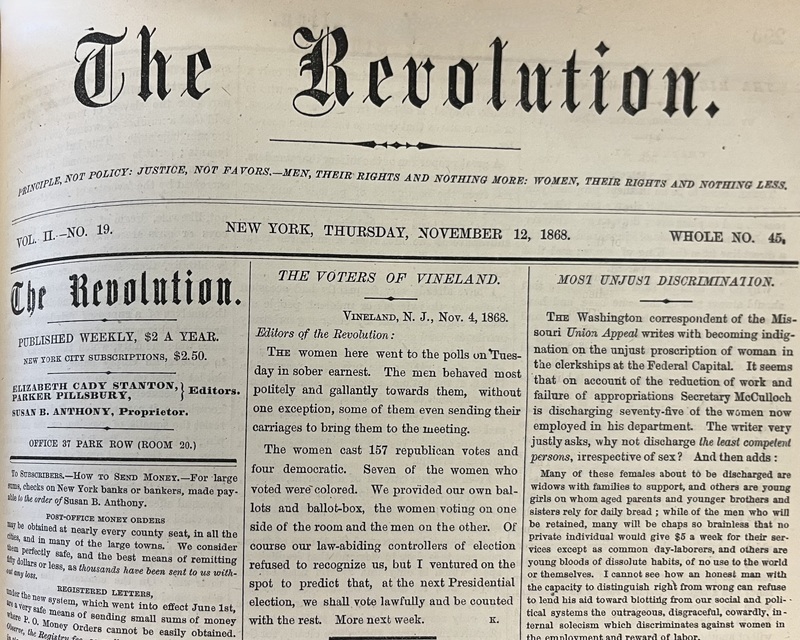

Mary Frances Burleigh: The Only Sister

Mary Frances Burleigh Ames Basics

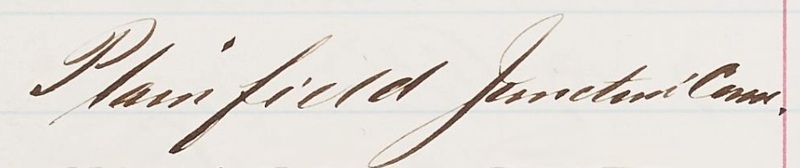

b. April 7, 1807, Plainfield, Connecticut

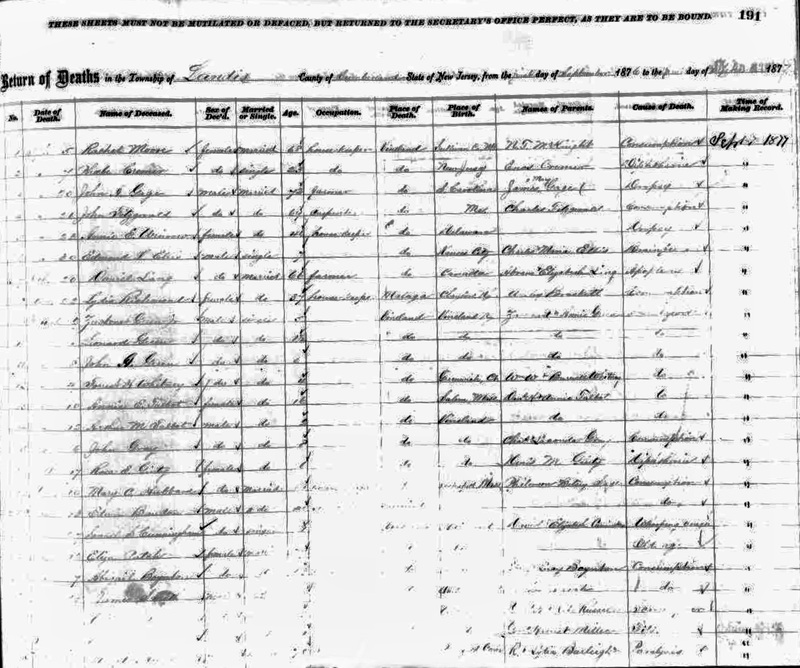

d. February 19, 1877, Vineland, New Jersey

m. Jesse Ames (1803-1890), October 11, 1854, Oxford, Massachusetts

lived in Connecticut through ca. 1863; New Jersey ca. 1863-1877

I. Early Life and Overview

Mary Frances Burleigh was the oldest child of Rinaldo and Lydia Burleigh, and the only surviving daughter. Being both the eldest and the only female likely predestined her for family caretaking; her late marriage made it clear that she was investing a great deal of energy into her birth-family. Her father's long decline in old age essentially kept her in Plainfield, and it is significant that she and her husband Jesse Ames moved out almost as soon as they reasonably could after his passing in early 1863.

All who have pursued the study of women's history know how frustrating it can be. We have only fragments of most women's lives, making the writing of narrative history, or even social history, a difficult task. In the case of Mary Burleigh, though, we are fortunate that these scattered records reveal identifiable phases in her life, as detailed below.

Of her earliest life we know very little. What formal education she might have received outside of the home (Connecticut district schools were far better than the national average) has yet to be discovered, but there is no doubt that she was living in a family that prized education, literacy, and culture. The fact that she was prepared to be a co-teacher with Prudence and Almira Crandall demonstrates that she had some knowledge of how to run a school, and was able to teach on an advanced level.

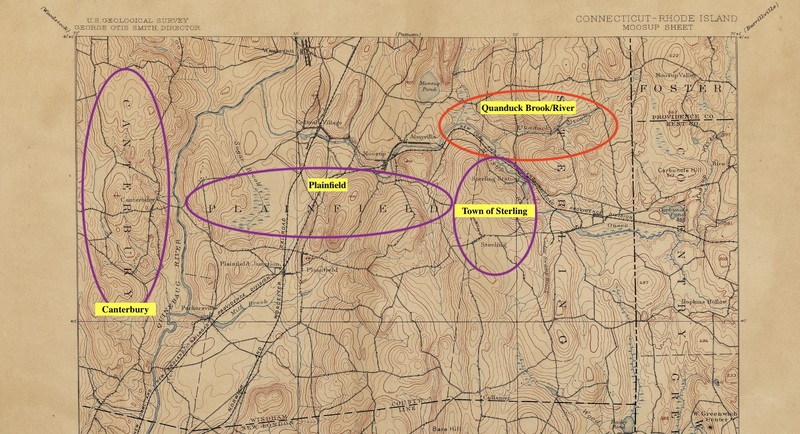

II. Mary in Canterbury 1833-1834

Mary Burleigh made a decisive start in her abolitionist engagement. Teaching alongside Prudence and Almira Crandall at the Canterbury Female Academy, Mary was enmeshed in the controversies surrounding the school, and participated in anti-slavery organizing.

Mary first began teaching at the Canterbury Female Academy in the summer of 1833. She was likely the first of the Burleigh siblings to be directly involved with this famed school - her brother William was in Schenectady until the fall, and Charles' work on The Unionist didn't begin in earnest until late July. Crandall scholar Susan Strane places Mary's arrival as a co-teacher in early July, when Prudence Crandall had a serious fever.

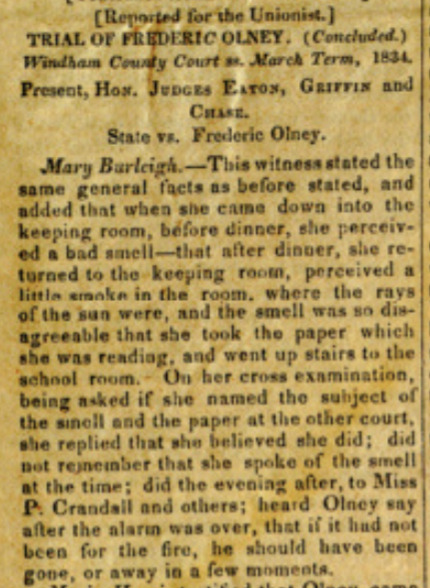

Mary's testimony in the trial of Frederick Olney, a free Black man, on false charges of arson, was part of the wave of evidence that resulted in his being acquitted in less than 15 minutes by an all white male jury. Her specific testimony included material directly from Olney, to wit, that he had not intended to stay much longer that day, until the alarm was raised and he stayed to fight the fire. This testimony placed Mary under cross-examination.

References

Rycenga, Jennifer. Schooling the Nation: The Success of the Canterbury Female Academy for Black Women. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2025. p. 103, 112, 140, 142, 166, 203.

Strane, Susan. A Whole-Souled Woman: Prudence Crandall and the Education of Black Women. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1990. p. 87, 166.

"The Trial of Frederick Olney," conclusion. The Unionist 1834-04-10.

III. Mary Burleigh's activism: Olney Trial and the Brooklyn Female Anti-Slavery Society

The two excerpts above demonstrate how Mary Burleigh's contact with the Black students at the Canterbury Academy led to deeper involvement and understanding. Remember that for any white woman of the time to be in regular social contact with Black men, as Mary was at the school, raised the hackles of the racist white majority. She weathered that crisis, and then when the white enemies of the school tried to frame Olney, she was able to speak forthrightly in his defense.

The Brooklyn Female Anti-Slavery Society was formed as a direct result of the school controversy. It represents a growing political acumen on the part of white women in the vicinity. Mary Burleigh taking a direct leadership role confirms what the Olney trial had implied - she made the turn from merely personal assistance to a larger vision of political and social change. Aside from the white men who spoke - all superstars of the movement (William Lloyd Garrison, Samuel Joseph May, and Charles Stuart) - the women leaders included one of Garrison's future sisters-in-law (Sarah Benson), and Olive Gilbert, who would go on to be the amanuensis to Sojourner Truth, for the first edition of The Narrative of Sojourner Truth. The Stetson family women were also well-represented in the Anti-Slavery Association; in a decade they would become residents and leaders in the multi-racial utopian Northampton Association.

References

"The Trial of Frederick Olney," conclusion. The Unionist 1834-04-10.

"Female Anti-Slavery Society." The Liberator 1834-08-16, republished from The Unionist 1834-07-10

Christopher Clark and Kerry W. Buckley, editors. Letters from an American Utopia: The Stetson Family and the Northampton Association 1843-1847. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004. Contains many letters from Dolly Witter Stetson, referred to as Mrs. James Stetson in the records of the Brooklyn Female Anti-Slavery Society.

The Liberator 1834-08-16, republished from The Unionist 1834-07-10

FEMALE ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY.

On Tuesday afternoon last, the adjourned meeting of the ladies of Brooklyn and vicinity was held in Mr. Davison’s Hall.

Prayer was offered by Rev. Mr. May. The committee appointed at the previous meeting to correspond with other Female Anti-Slavery Societies, reported that they had written to the Societies, in Philadephia, New-York and Boston. One letter in answer had been received—and that a very interesting one from Lucretia Mott of Philadelphia. It was read by Mrs. Herbert Williams.

The meeting was then addressed at considerable length, and in a very impressive manner, by Charles Stuart, Esq. He pointed out the peculiarities in the character and circumstances of woman, which enable her to be an important instrument in all moral reforms.

Mr. William Lloyd Garrison and Mr. May also offered some remarks to encourage the philanthropic, for which the meeting was then convened.

A form of Constitution was then read and adopted as follows:—

Constitution of the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Brooklyn and vicinity.

Preamble.—Whereas the system of slavery which exists in a portion of this land is contrary to every principle of humanity, honor, and religion, is derogatory to the character of our country abroad, and injurious to its peace and prosperity at home, and renders us obnoxious to the righteous condemnation of the Most High.

And whereas more than a million of our own sex are now groaning under the yoke of an insupportable and most degrading bondage, unprotected by law, or by any sense of manly shame, from merciless stripes and cruel outrage, are subjected by a traffic in the bodies of human beings, more dreadful than death, to the sudden and cruel sundering of the most sacred relations of domestic life, are deprived of knowledge, and as far as the power of their oppressors extends, of the hopes of the blessed gospel.

And whereas the demoralizing influence of this atrocious system, by inducing woman to sanction and even voluntarily to practice its barbarities, often renders her even more deserving of the commiseration of Christians than when she is its involuntary victim,—sin being so much greater an evil than suffering.

And whereas an enlightened and Christian public sentiment alone is, under God, likely to abolish this atrocious and complicated system of iniquity, to arrest from our country the impending judgments of the Almighty.

And whereas, female influence is calculated to effect great good in such a cause, as has been abundantly shown in the abolition of British Colonial Slavery.

We therefore, in behalf of ‘the suffering and the dumb,’ desiring to exercise towards both the oppressor and the oppressed the spirit of Christian benevolence, and imploring the Father of all mercies for his guidance and aid, in our efforts to subserve his will in this most holy cause, do agree to form ourselves into a Society to be governed by the following

CONSTITUTION.

1. This Society shall be called the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Brooklyn and its vicinity.

2. The objects of this Society shall be, First, to aid in the diffusion of information on the subject of Slavery; to portray its true character; to prove its utter indefensibleness on any principle of religion, justice or expediency. Second, to promote the elevation of the colored people of our country to the equal enjoyment with ourselves of these rights and privileges which are acknowledged to be inalienable, as the birthright of man. Third, to aid in general the American Anti-Slavery Society in its benevolent objects.

3. Any female approving the principles of this Society, and contributing to its funds, shall be a member.

[Here follow the usual articles for the government of the Society.]

Twenty two ladies then subscribed their names as members of the Society—and made choice of the following officers.

President, Mrs. Herbert Williams

Vice President, Mrs. Maria W. Lyon

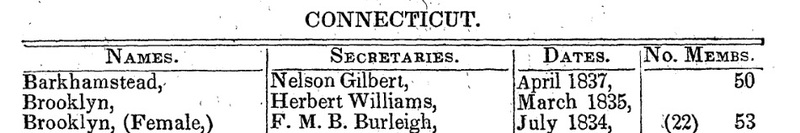

Miss Mary Burleigh, Secretary.

Miss Sarah Benson, Treasurer.

Miss Lucretia Lee, Librarian.

Managers.

Mrs. Syrena Sharpe, Miss Martha Smith, Mrs. Louisa Williams, Miss Olive Gilbert, Miss Martha E. Williams, Miss Elizabeth Mather.

IV. Mary Burleigh after Canterbury (1835-1854)

Mary Burleigh came to the aid of the Crandall family once again when her co-teacher, Almira Crandall Rand, was dying of consumption in 1837. In the May 1837 Annual Report of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Mary Burleigh is still listed as the secretary of the Brooklyn Female Anti-Slavery Society.

After her father's blindness forced his retirement - likely before 1840, but no later than 1850 - Mary was apparently sidelined from visible activism by an increasing burden of elder care. Yet when she is described in letters from her brothers, her sense of fun and joy, their delight in her, is obvious. My guess is that she wore the mantle of eldest sibling with grace and good humor.

For instance, Charles tells their youngest brother, George, to tease Mary about her laggard letter-writing:

"Tell Mary I am waiting for a letter from her one of these days, & she’d better be after writing it, if she don’t want to be pasted in the Freeman as a delinquent & have a bill made out against her, for pen, ink & paper wasted in writing to her." [The Pennsylvania Freeman was the newspaper Charles was editing at the time, in Philadelphia]

These letters also note that Mary Burleigh went to Oxford to help Evelina and John Burleigh with the birth of a child in early 1842 (it would turn out to be their long-lived son Charles Hartwell Burleigh). Aware of the trip, Charles asks George about the results:

"Do you hear anything yet from Mary & the Oxford folks?—how they are?—& what they call the younker last arrived? — & when Mary expects to be at home again?"

Mary Burleigh was conscientious about caring for others, a fact that comes through in almost every scrap we have concerning her. But her disappearance from public activism - even in a family whose men would prove to be quite pro-feminist - is disappointing.

A most tantalizing hint of Mary's wider intellectual interests surfaces in relation to Bronson Alcott's "Conversation" series. There is a Miss Burleigh listed as a participant in a Conversation session that commenced in December 1848 and ended in January of 1849. While we have not yet been able to corroborate this as Mary Burleigh, there are no other likely candidates from the Burleigh family of Plainfield, nor that of the Burleighs of Maine. If this does prove to be Mary Burleigh, it would be a most interesting extension of her life into the philosophic currents of the day.

References

Alcott, Amos Bronson, Notes of Conversations, 1848-1875, ed. Karen English, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007, p. 58, 247.

American Anti-Slavery Society. Fourth Annual Report of the American Anti-Slavery Society, with the Speeches Delivered at the Anniversary Meeting Held in the City of New York, on the 9th May 1837, and the Minutes and the Meetings of the Society for Business. New York: William S. Dorr, 1837.

Burleigh, Charles C., letter sent to George Shepard Burleigh, December 3, 1840. In the George S. Burleigh collection, HA 1185 at the John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Burleigh, Charles C., letter sent to George Shepard Burleigh, April 3, 1842. In the George S. Burleigh collection, HA 1191 at the John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Burleigh, Cyrus Moses. “Journal commencing on the first day of July, 1837 and diaries,” in American Poetry, 1650-1900: Part II. New Haven: Research Publications, 1975. entries of August 17, 1837 forward deal with the last illness and death of Almira Crandall.

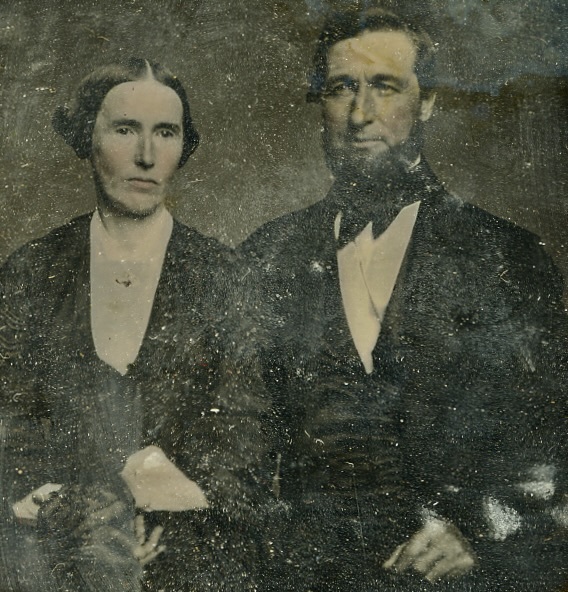

V. Marriage to Jesse Ames

Mary Burleigh's marriage to Jesse Ames, and their relocation to Vineland New Jersey, are shrouded somewhat in mystery. Jesse Ames hailed from Sterling, Connecticut, the town neighboring Plainfield to the east (and bordering on Rhode Island). His parents were Dyer Ames and Rosanna Burden Ames; his father was involved in early manufacturing in Sterling, helping to establish the American Cotton Manufacturing Company "near Ransom Perkins' fulling mill on Quandunk River." Dyer and Rosanna had a large number of children, including their youngest son, William, who would have been known to the Burleighs because of his appointment in 1850 as one of the Deacons at Plainfield Congregational Church, where Rinaldo Burleigh had long served that role.

Jesse Ames was Dyer and Roseanne's second son, and a life-long farmer. Together with his elder brother John (an accountant), he was living with his parents in 1850. When his father died in 1853, Jesse received a quarter share in the family farm (which was worth $9,000, roughly the equivalent of $300,000 today). His mother passed away less than a year later, in early 1854. One is tempted to think that, like Mary Burleigh, Jesse's life involved extensive elder care, since he married Mary Burleigh soon after his parents had died.

Adding to the surfeit of mysteries here, Jesse and Mary's marriage on October 11, 1854 was solemnized in Worcester, Massachusetts. Perhaps they were eager to include the family of Mary's late brother John, whose widow Evelina was close to Mary.

The 1860 census shows the Ames living in the same household with Mary's father Rinaldo, and her brother Lucian Burleigh, his wife Elizabeth, and their growing brood of little Burleighs. Due to her marriage coming so late in her life, it is not surprising that Mary and Jesse did not have any children of their own.

References

Larned, Ellen D. History of Windham County, Connecticut: A Bicentennial Edition. 2 volumes. Chester CT: The Pequot Press, 1975 (1874).,vol. 2, p. 402.

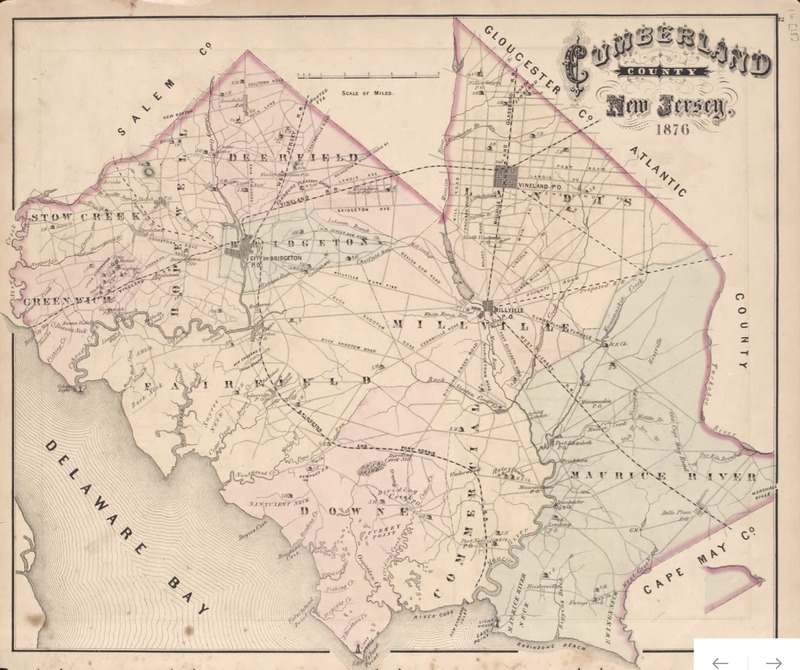

VI. Vineland, Utopia and Scandal

Jesse Ames and Mary Burleigh Ames moved to New Jersey after the death of her father Rinaldo. The earliest evidence we have of their new home is in a property deed, in Mary's name, dated July 3, 1867. Mary and Jesse appear to have been part of a miniature migration of New England and Pennsylvania farmers to the newly-established town of Vineland in southern New Jersey. The founder of this intentional city, lawyer and real estate developer Charles K. Landis (1833-1900), was quite a compelling figure in his own right. His stated goal for Vineland assuredly appealed to the Ames as they sought to begin a new chapter in life:

"...to found a place which, to the greatest possible extent, might be the abode of happy prosperous and beautiful homes. To first lay it our upon a plan conducive to beauty and convenience, and in order to secure its success, establish therein the best of schools. Different branches which experience has shown to be beneficial to mankind; also manufactories, and different industries, and the churches of different denominations. In short, all things essentual to the prosperity of mankind but, at the same time, under such provision for public adornment and the moral protection of the people, that the home of every man of reasonable industry might be made a sanctuary of happiness and an abode of beauty, no matter how poor he might be. In fact, I desire to make Vineland so desirable a place to live in by reason of its various privileges and over all to throw such a halo of beauty as would make people loath to leave it, and, if they did so, would draw them back again."

Because Vineland has an interesting history - including Landis's murder of an unfriendly newspaper editor - more research into this final phase of Mary Burleigh's life is necessary. We do know that Jesse Ames had enough prominence and expertise that he served as the Town Assessor in 1876. Such a position would require education, strong numeracy, and an understanding of the importance of property value and taxation policy in a relatively young town. The Ames lived near the intersection of Spring Avenue and Landis Avenue (the principal thoroughfare of the town, named by and for its founder), in an area that was outside of the business district and intended for farming; indeed, the widowed Jesse Ames is listed in a column of "Vineland Farmers" in the 1881-1882 Directory.

References

Vince Farinaccio, Before the Wind: Charles K. Landis and Early Vineland. Lulu.com publisher, 2018.

Fernanda Perrone, et. al., On Account of Sex: The Struggle for Women's Suffrage in Middlesex County. Online Exhibit, Rutgers University Library, 2021.

Landis quote from this archived website of the Friends of Historic Vineland.

Cumberland Co. Directory for 1871-72. Containing the names of the Inhabitants of Bridgeton, Millville and Vineland, a Business Directory, Together with a Town Business Directory, and Much More Useful Miscellaneous Information. Millville, NJ: J. H. Lant, 1871.

"Township Officers," Evening Journal (Vineland, New Jersey), May 10, 1876, page 1.

W. Andrew Boyd and S. Fred Boyd, compilers. Boyd’s Cumberland County Directory, for 1881—82. Containing a General Directory of the Cities of Bridgeton, Millville and Vineland, together with a Complete Business Directory of the Whole County, giving the Names of all Professions, Trades and Occupations, and a very Large List of the Farmers and Fruit-Growers. No place given: Boyd Brothers, [1881].

"Cumberland, New Jersey, United States records," images, FamilySearch , Sep 9, 2025), image 82 of 693; Cumberland County (New Jersey). County Clerk. Image Group Number: 008590967. Material located by Kate Blankenship.

VII. Mary's final return to Plainfield

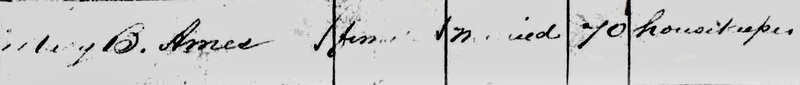

Mary Frances Burleigh Ames died on February 19, 1877, in Vineland, New Jersey. The official death records give "paralysis" as the cause of death, and her occupation as "house-keeper," which likely would indicate that her paralysis had not been a lengthy one. Because she was to be buried in Plainfield, there is a record of her corpse in the New York City Health Department's rigorous "Bodies in Transit" ledger. Started in the late 1850s, presumably to address vectors of possible disease and criminality (grave-robbing being a regular practice among medical students), many famous names dot its pages, including the executed Abolitionist John Brown and the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln.

So far no record of any formal religious funeral services or burial rites for Mary have been uncovered. She had but three surviving siblings, but they all lived close enough to potentially attend an event, given the lag between her death and the return of the body for burial. Charles was in Northampton, George in Rhode Island, and Lucian had remained rooted in Plainfield. Perhaps there are letters, documents, or family memories yet to be uncovered that would tell us what happened.

When he died in Vineland in 1890, Jesse Ames' body also went back to be buried alongside Mary in Plainfield Cemetery.

References

Bodies in Transit, volume 9, 1874-1880, New York, New York. City Inspector's Office, Bureau of Records and Statistics, and Department of Health. Online version available through the New York City Department of Records and Information Services. The entry for Mary Burleigh Ames is on page 5 in the original ledger book, and pages 14-15 in the web-based version.

Ancestry.com. New Jersey, U.S., Birth, Marriage and Death Records, 1711-1878 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2022. Original data: Birth, Marriage and Death Records. New Jersey State Archives, Trenton, New Jersey.