William Henry Burleigh: Earnest and Affable Editor

William Henry Burleigh Basics

b. February 2, 1812, Woodstock, Connecticut

d. June 13, 1871, Brooklyn, New York

m 1. Harriet Adelia Frink (1812-1864), December 14, 1834, North Stonington, Connecticut

m 2. Celia Tibbits (1826-1875), September 7, 1865, Troy, New York

lived in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and New York at various points in his life

I. Overview of William Henry Burleigh's Life and Work

William Henry Burleigh was an eloquent and loving spirit, intertwining literature and justice, always ready to expand his views, while staying steady in his principles. He was the most capable editor among the Burleigh brothers, from a technical as well as political perspective, having received a genuine if scattered apprenticeship in the newspaper business.

William Henry Burleigh had a constant urge to combine literature, the arts, and reform. He tried to include what he considered high quality prose and poetry in the pages of his newspapers, and started literary journals at many of his stops (though with limited success). His own poetic output was substantial; he also did much to encourage the career of his younger brother George.

At the time of the Abolitionist schism, he was among the Liberty Party faction. This put him at odds with his own brother Charles, and many previous allies and friends. When he decided to call a truce in this faction fight, it coincided with his leaving Abolitionist editing for a decade, before the new Republican party called forth his talents again to aid in the campaigns of 1856, 1860, and 1864.

William had married Harriet Frink in 1834, soon after the closure of the Canterbury Female Academy where he taught. There are very few hints about their marriage, or about her at all. By contrast - but perhaps affecting the quality of their relationship - a theme emerges in much of William's writing, complaining about not being paid, about being pinched for money, about subscribers being laggard in their dues, and so forth.

From 1863 to 1865, William's immediate family suffered many tragic losses: his father, his wife, one of his daughters and one of his sons all died in that short time span. William remarried at the end of 1865, to a woman who had become a friend and ally - Celia Tibbits. She was an important feminist organizer, and a religous liberal and free-thinker, who went on to be one of the first women ministers in the Unitarian church, occupying the same pulpit in Brooklyn, Connecticut that Samuel J. May had occupied back in the 1830s.

A tentative outline of his life's major chapters:

1812-1833 - Childhood, education, apprenticeship in journalism in Norwich, Stonington, and Schenectady

1833-1834 - Canterbury Female Academy and The Unionist; marriage to Harriet Frink

1834-1835 - Schenectady and The Wreath

1835-1837 - eastern Massachusetts: editing, and anti-slavery Agent

1837-1842 - Pittsburgh area, editing The Christian Witness and Temperance Banner

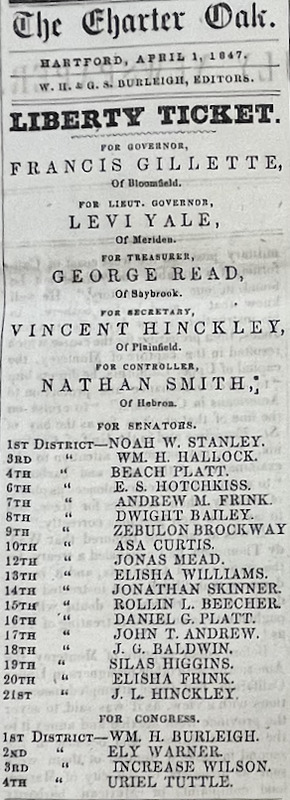

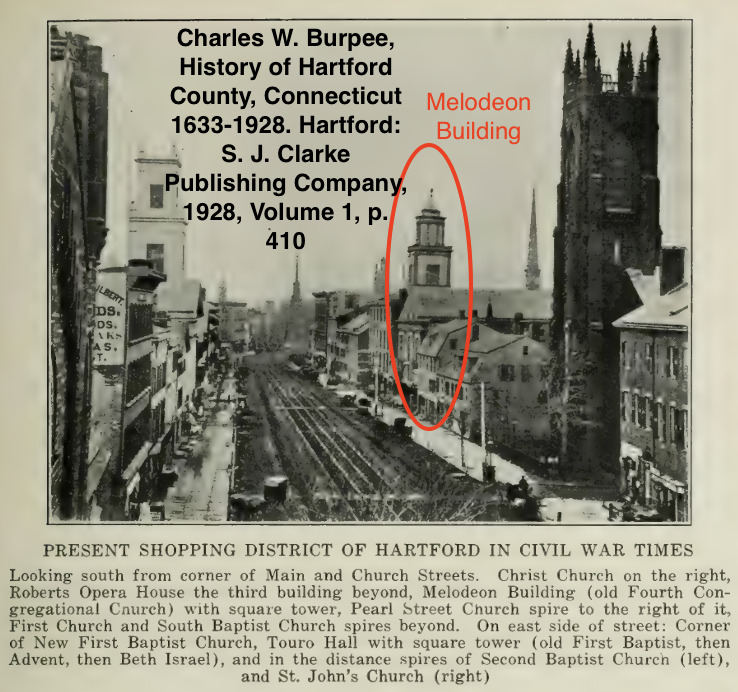

1842-1849 - Hartford, editing The Christian Freeman/The Charter Oak, and the The Non-Pareil

1849-1855 - Syracuse area, working for the New York State Temperance Association, some editing

1855-1871 - Harbor-master of New York City; Republican campaigning; death of first wife Harriet (1864); marriage to Celia Tibbits (1865); his death in March 1871. Cause of death may be related to epilepsy.

II. William Burleigh's Editorial Style, Flair, Strengths & Liabilities

This is a good example of William's editorial writing.

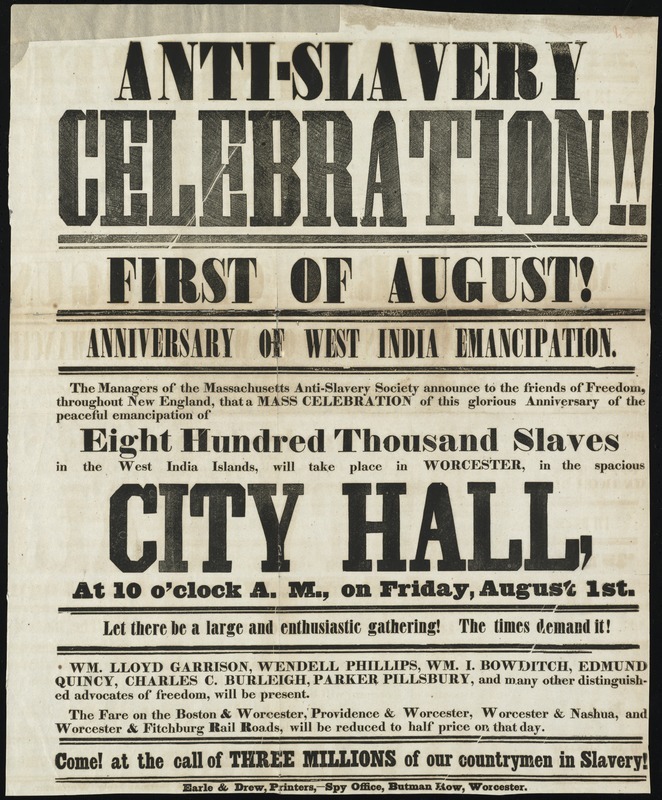

THE FIRST OF AUGUST.

We love our own memorable day the Fourth of July—but we confess the First of August brings to our heart a purer, a more unalloyed delight. And as it approaches once more, it is a pleasure to recall to recollection some of the features of the great event which then transpired.

The spirit of humanity, which was awakening some sixty years ago in the British Empire by the labors of Clarkson and his associates, attained for its first object the abolition of the Slave Trade. But it did not stop at that partial achievement. It came next to consider the case of actual British bondmen. The boast had been that “Slaves could not breathe in England,” but a system of oppression prevailed in her West Indian Colonies; and the cry of her hundreds of thousands, pining amid their toils and stripes, had hitherto died away on the intervening ocean, and entered into no British heart. Now it was heard and a band of energetic souls embarked in the enterprise of emancipation. The struggle was long and arduous. It met with the same astonishing apathy, the same under current of interested sympathy with the oppressor, which has thus far borne back the cause of Freedom in our own land. But the truth long clamored down, triumphed at last. The stern and desparate [sic] opposition of a wide=spread and powerful West India interest, was at length overcome, and the work achieved.

A bill was passed, substituting in the place of unconditional slavery, a system of apprenticeship to be of force through the British West Indies on the 1st of Aug. 1834, with entire emancipation for one class of slaves in 1838, and the rest in 1840. This plan had its origin in the old prejudice that slaves must be prepared for freedom/ And this Apprenticeship was to prepare them! In two of the Islands, Antigua and Bermuda, a better wisdom prevailed, immediate emancipation was chosen instead of the Apprenticeship, and twelve years ago the coming 1st of Aug. 34,000 souls passed at once from the most rigorous bondage to entire freedom! At the late period of ’38, ’40, after an intermediate period of apprenticeship, more vexatious and intolerable to all parties concerned than unmitigated bondage, 800,000 [could be 600,000] more, more than ever unfitted for the boon, came at once into the possession of their liberty!

And what was the result! Exasperated by the worst wrongs that man can inflict on man; smarting from the recent scourge of the task-master, or just emerging from the thousand more vexatious inflictions of the apprenticeship—outnumbering the enervated whites, their recent injurers, in some islands at the rate of thirty to one, and in all on an average, or more than six to one—they signalized, did they not, the first hour of their liberty with carnage and blood? It was an hour, was it not, of merciless revenge, of fierce triumph on the part of the emancipated, wiping out the long score of their wrongs in the blood of the whites? It was in their power. And the wounds of their spirit were still fresh and bleeding. It was feared by their oppressors. A voice within them bade them tremble lest the hour of Freedom should be the hour of retribution. And on that last night of July, as the last sands were running in the hour-glass of Slavery, when many thousands of their long enslaved and bitterly wronged bondmen were about to rise from their chattelism, as free and far more powerful than themselves, the planters of Antigua watched away the anxious hours behind bars and bolts and arms, fearing the fire and carnage they had so often predicted.

But was it so? Was it a scene of wild tumult and consternation? Where were they, the candidates for freedom, at that eventful midnight? Not mustering darkly around the banner of insurrection.—Not scattering firebrands, arrows and death, among their guilty oppressors, now in their power; but gathered in God’s temples, pouring out their grateful in God’s temples, pouring out their grateful souls in prayer—yes, on their knees, with streaming eyes and bursting hearts, lifting their hands to heaven in transports of grateful joy! A more thrilling scene can scarce be found in human history. In one word, the great change from Slavery to Freedom took place not only without bloodshed and confusion, but with less of trouble and suspension of business than would attend the simultaneous transfer of as many free New England laborers from one employer to another.

Years have now passed away since this glorious measure was achieved! And with all its results it has gone upon the page of history. We have, indeed, had rumors of trouble and tumult in the West Indies. “The wish has been parent” for the most part, to such reports. They had been so confidently predicted, that many a prophet of evil could not refrain, in the utter absence of facts, from fashioning some sort of fulfillment to his prophesyings. The slightest disorder, whether resulting from the hard-handed policy of the whites, or from the just sense and exercise of liberty on the part of the new freemen or from any other cause however disconnected with the liberation of the blacks has been magnified and heralded through the world. It was poor comfort and could not last. Even the N.Y. Observer grows tired of it; and the secular press, after years of resistance, begins to admit that West India Emancipation was a peaceful and blessed event—that 800,000 slaves were at once “turned loose,” and by their magnanimous conduct, by their quietness and industry and rapid rise in civilization and refinement, have falsified and put to shame every prediction of evil.

When shall this great lesson be heeded by our country?

The Charter Oak, New Series, 1:30:2 July 30, 1846

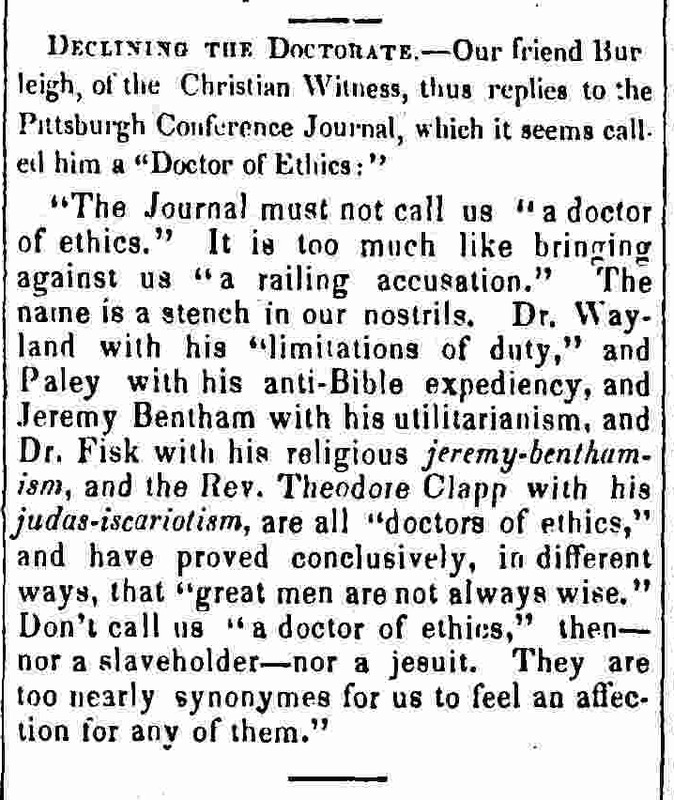

III. "Declining the Doctorate"

This brief piece "Declining the Doctorate," comes from early in William Burleigh's tenure as editor of the Pittsburg Christian Witness. It was reprinted in the Pennsylvania Freeman by his friend, John Greenleaf Whittier. Burleigh balances wit and righteous anger against hypocrisy in a delicious blend. He was near the top of his game as both a writer and an editor here. The "Journal" in question was the "Pittsburgh Conference Journal" of the Methodist denomination.

The Journal must not call us "a doctor of ethics." It is too much like bringing against us "a railing accusation." The name is a stench in our nostrils. Dr. Wayland with his "limitations of duty," and Paley with his anti-Bible expediency, and Jeremy Bentham with his utilitarianism, and Dr. Fisk wth his religious jeremy-bentham-ism, and the Rev. Theodore Clapp with his judas-iscariotism, are all "doctors of ethics," and have proved conclusively, in different ways, that "great men are not alwayss wise." Don't call us "a doctor of ethics," then—nor a slaveholder—nor a jesuit. They are too nearly synonymes for us to feel an affection for any of them.

"Declining the Doctorate," from the Pittsburgh Christian Witness, reprinted in Pennsylvania Freeman 5:2:3, September 20, 1838.

IV. Political Abolitionism

William Burleigh belonged to all three of the major anti-slavery political parties, in succession: The Liberty Party, the Free-Soil Party, and the Republican Party. He parted ways ideologically here from his brother Charles (and later Cyrus).

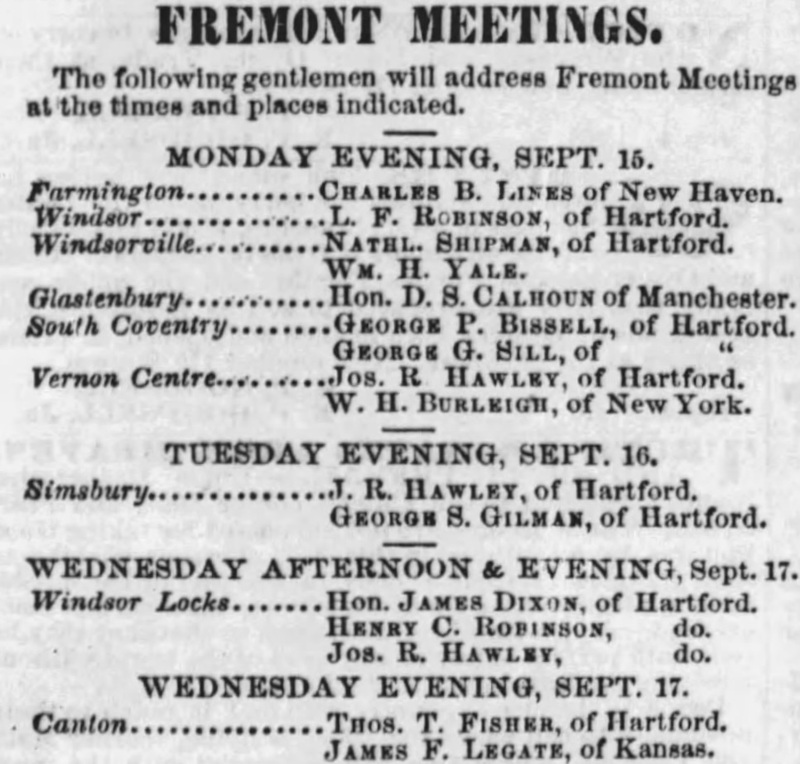

In 1856, although he was resident in NYC, he came back to assist the new-born Republican Party by speaking - alongside famed Connecticut politican Joseph Hawley - at a Frémont campaign event in Vernon, Connecticut.

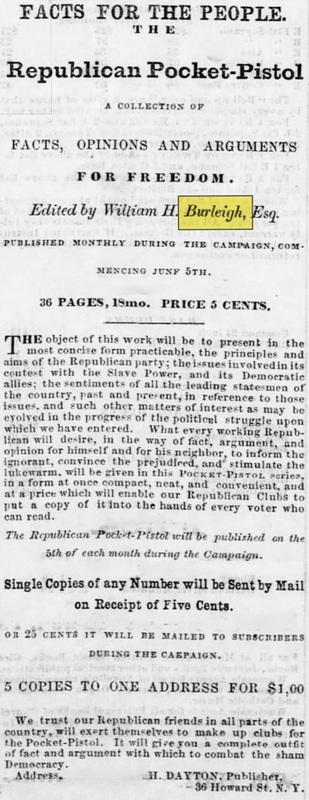

By 1860, Burleigh's compediums of songs and summaries were becoming a staple of campaigns, as seen by the Republican Pocket-Pistol and Songster that he edited for Lincoln's successful election run.

This section is incomplete. There is a cornucopia of primary materials that needs to be sifted, sorted, and analyzed. Stay tuned!

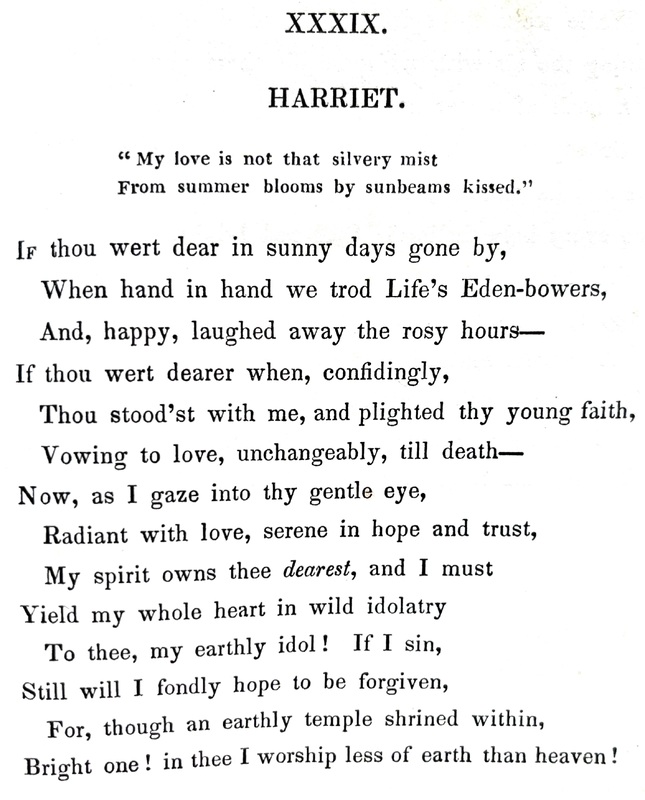

V. Poetry of William Henry Burleigh

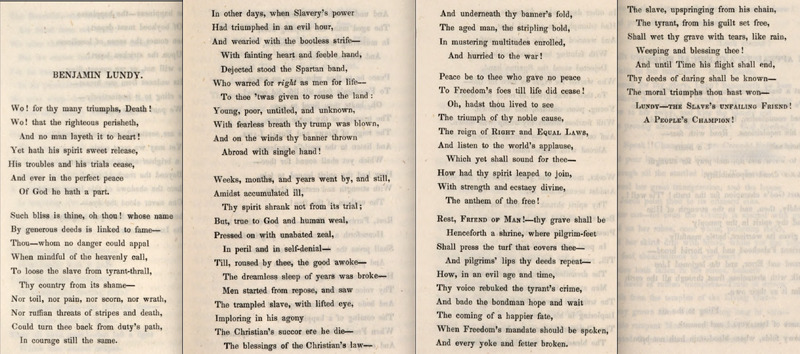

The poetic themes taken up by William Henry Burleigh ranged across personal and political topics. Unlike his more literarily accomplished brother George, William rarely tried larger forms, content with shorter poems that could fit the niche in the journals and newspapers of the day. Over two dozen of his poems are in use as hymns, including translations into Tamil, Hawai'ian and Lakota, according to Hymnary.com.

There were a few instances, though, where William tried larger forms, most notably in the publication of Our Country (1841) and in the public "performance" recitations of "The Golden Age" that he undertook in the 1850s.

William H. Burleigh was admired by other poets, most notably his fellow reformer John G. Whittier, who described him as a "gifted" when reprinting his memorial poem to Benjamin Lundy. While William's fame as a poet was simply another component of his overall reformer portfolio, the respect his efforts garnered provided him with the ability to mentor his younger brother when George was first gaining accolades for his work. The solicitious care that both William and Charles had for their youngest brothers Cyrus and George is touching, and effective, as both Cyrus and George became leading Abolitionist and reform figures in their own right.

The Burleigh team is assembling what we believe will be the first full catalogue of William's poetic works. Stay tuned for this development.

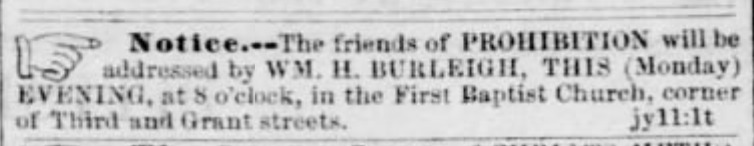

VI. William H. Burleigh's Temperance Campaigns of the 1850s

When he left the editorship of The Charter Oak to take a position with the New York State Temperance Association in 1850, William's emphasis shifted dramatically from Abolition to Temperance. One source indicated that he was tired of the factionalism in Abolition circles. He did not abandon the cause of Anti-Slavery entirely, and the rise of the Republican Party (as well as his move to New York City and Brooklyn) would re-energize him. But for the first half of the 1850s, he was focused on Temperance.

As part of this, and with the rise in the success of the Maine Prohibitory Law (that closed all liqour stores), Burleigh also was in demand as a lecturer-agent. One such excursion, in July-August of 1853, saw him give over 40 presentations in as many days in western Pennsylvania and a smattering few in Ohio. Wisconsin wanted him, too, but he was called back to his main job with the New York State Temperance advocates.

VII. Harbor-Master Position

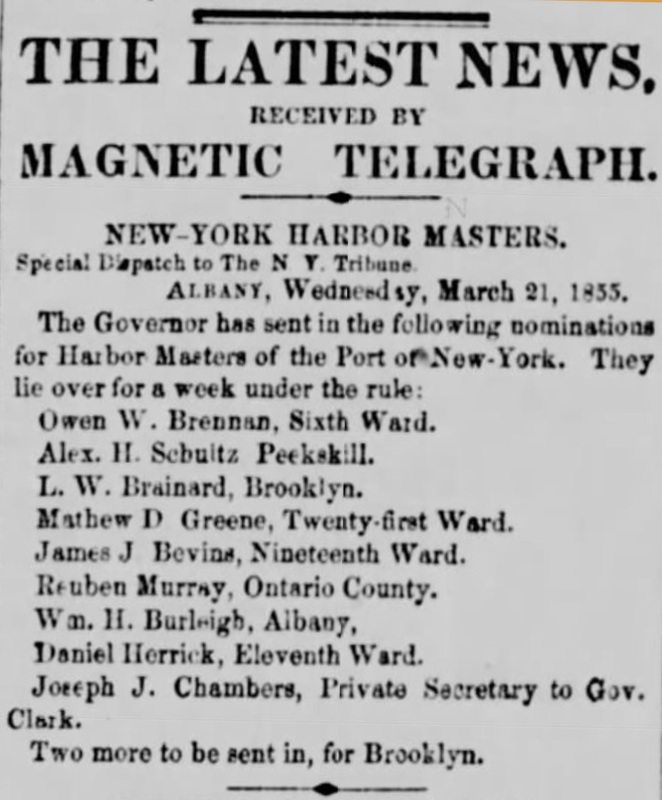

In 1855, the newly-elected governonr of New York, Myron Holley Clark, was a friend of William Burleigh's, and a strong advocate of Temperance. In one of his first official acts, he appointed William Burleigh to one of the New York City Harbormaster positions.

The press was befuddled by this seemingly odd choice of an Abolition and Temperance editor to a position that called for some actual business sense! Whatever William's qualifications were, and whatever Clark intended, there can be no doubt that this position provided William with a reliable and steady income for the next decade and more.

In her biographical sketch of William, his wife Celia remarks "I wonder how it was possible for him in addition to the duties of his office, — which was no sinecure, — to accomplish so much. Not one who dashed off a poem or letter at a sitting and without effort, but a conscientious worker, never satisfied with less than his best" (xxvii-xxviii; emphasis added). The fact that she needs to state that the job was not a sinecure, leads one to think that people accused him of having accepted a sinecure...

VIII. William Burleigh's First Marriage to Harriet Frink

The core generation of Burleighs generally made marriages that were not only strong unions, but radiated out into other dimensions of social, political and artistic areas. William's first marriage, to Harriet Frink of North Stonington, is a major exception to this trend. The facts as they are currently known are flimsy, but suggest tension or resignation more than mutuality. So far no letters from Harriet have been uncovered, no photographs or portraits, no mentions in the columns of newspapers.

Frink family in North Stonington.

One thing is clear - the marriage itself, conducted in December of 1834, followed close on the heels of a string of tragedies and terror. September 1834 had witnessed the Canterbury authorities focusing on William for prosecution under the Black Law, given his prominence as a teacher at the school run by Prudence Crandall. Their legal efforts were rendered moot when the school was horrifically destroyed by a vigilante mob. That did not mean, though, that the efforts to pursue William legally were dropped. In any case, William quickly relocated to Schenectady, and after the December wedding took his new bride with him.

From her perspective, she was the youngest of ten children born to William and Wealthy Frink. Harriet's oldest sibling was eighteen years her senior. In 1833, when Harriet was 21, her mother died. Her older sisters were all married; she likely was fated to elder care for her father if she didn't marry.

There was another traumatic event, though, in the Frink family. On September 25, 1834, Harriet Frink's young nephew George E. Miner (1830-1834), only child of her sister Mary Ann and her husband Gilbert Miner. The promise of this young boy, and the agony of his death, is preserved in two poems by William Henry Burleigh, who was deeply affected by the loss. So a theory that the losses of her mother and her nephew might have predisposed her to marriage seems plausible.

It is only fair to note that William's financial prospects were not good at the time of the wedding, and failed to measurably improve until the last decade that he and Harriet were together.

Harriet Burleigh is less visible in the historical record than any other Burleigh spouse. However, she was a committed antislavery advocate. She was in attendance at the conferences in the ill-fated Pennsylvania Hall. During the afternoon meeting of the Antislavery Convention of American Women on May 17, 1838, Harriet Burleigh, along with Mary Grew and others, dared to exit the hall to remonstrate with the crowd, asking them for peace. Bartholomew Fussell, an eye-witness to the event, described how the women

While their plea was ineffective - the mob began their destruction of the Hall immediately after the women's meeting broke up - the bravery of Harriet Burleigh and Mary Grew and threee other women delegates, is undeniable and moving.

Another literally interesting appearance for Harriet emerges in a letter written by Elizabeth LeBreton Gunn, wife of Lewis Gunn, an Abolitionist who had worked closely with Charles Calistus Burleigh. LeBreton Gunn was writing from California in August of 1851, where she had "read in one of the papers that Mrs. Will Burleigh and her two daughters attended an abolition meeting "dressed in bloomer costume." This is corroborated by an earlier brief note in the Massachusetts Spy newspaper that makes reference to "Mr. Burleigh's wife and daughter's attended the abolition convention at Syracuse, dressed in the Bloomer Costume - loose trousers, frock coat and straw hat." Both the time and the place - Syracuse in 1850 - dovetail perfectly with William Burleigh's move there. Given that the Bloomer outfit had only been invented in 1849, this makes Harriet Burleigh an early adopter of this reform in women's dress. The two daughters in question would have been Harriet and Lydia, the two oldest surviving daughters of William and Harriet Burleigh at that time.

Sources

Anna Lee Marston, editor. Records of a California Family: Journals and Letters of Lewis C. Gunn and Elizabeth Le Breton Gunn. San Diego: no publisher given, 1928. Reprint editionTuolomne County Historical Society, Sonora, California, second reprinting, 2001. p. 151.

Massachusetts Spy (Worcester), May 14, 1851.

Beverly C. Tomek. Pennsylvania Hall: A "Legal Lynching" in the Shadow of the Liberty Bell (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 125-126.

Bartholomew Fussell, "The Burning of Pennsylvania Hall: Account of an Eye-witness, Dr. Bartholomew Fussell," part two, Friends Intelligencer and Journal 53:8:125 (February 22, 1896).

IX. William Burleigh's Second Marriage to Celia Tibbits, and his Death

Celia Tibbits was a public personality at the time of her marriage to William Burleigh after Harriet's death. There are rumors that the marriage of Celia and William was a difficult one, but I can find no evidence to support a "separation" (either official or unofficial). On the contrary, she becomes a doting aunt, and a dedicated spouse who worked to make William into more of an avowed supporter of women's rights than previously he had been. She oversaw the publication of an additional volume of his poems, with an invaluable life sketch in it, at the time of William's passing.

His death brought forth many reminiscences, but none are more poignant than this sonnet by Theodore Tilton

WILLIAM HENRY BURLEIGH

Is this the only tribute we should pay—

These funeral flowers that on his bier belong?

Himself a singer, he deserves a song;

But who has any heart to sing to-day?

Should any stranger chance to come this way,

And view with tearless eyes, this lump of earth,

And call to witness for its living worth,

O, loving are the words we then could say!

But since to make a memory for our dead,

His virtues—Truth, Faith, Honor, and the rest—

With one loud-chanted requiem all have said,

"Behold, our chosen dwelling was his breast!"

Since tongues like these have spoken, dumb be ours!

So let us sweetly leave him with his flowers.

THEODORE TILTON

References

Theodore Tilton, "William Henry Burleigh," The Revolution (New York City) 7:16:1 (March 30, 1871); reprinted in Celia's sketch in Poems, p. xxxviii.

X. Politico-Aesthetic Theories of William Burleigh

William Burleigh loved literary pursuits, and proved himself an excellent judge of artistic efforts. As an early encyclopedia biographer of his pointed out, "whenever he could command the means for it, he would establish a purely literary paper, which, though generally short-lived, always contained gems of poetry and prose from his prolific pen."

William Burleigh was unafraid of appealing to a wide variety of audiences, though. As scholar Derek Scott analyzes, Burleigh specifically defended his editing of the Republican Presidential campaign songsters, rejecting "those who criticize campaign songs on the grounds of triviality, arguing that it is wrong to label 'trivial' anything that stirs hope and raises human aspirations." Burleigh himself writes

If there are some things here that offend the fastidious, let such reflect that those very things may have a power to stir into activity some honest heart that could scarcely be reached by more refined and subtle modes of expression. It must be obvious, too, from the very necessity of the case, that, in a work like this, adaptation to the popular taste must take precedence of any purely aesthetic considerations. (The Republican Campaign Songster for 1860, iv; quoted in Scott)

References

Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography, edited by James Grant Wilson and John Fiske. Revised Edition. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1900. Volume 1, p. 455

Derek B. Scott, "The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900." in Watt, P, Scott, D.B. and Spedding, P, (eds.) Cheap Print and Popular Song in the Nineteenth Century: A Cultural History of the Songster. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 73-90.

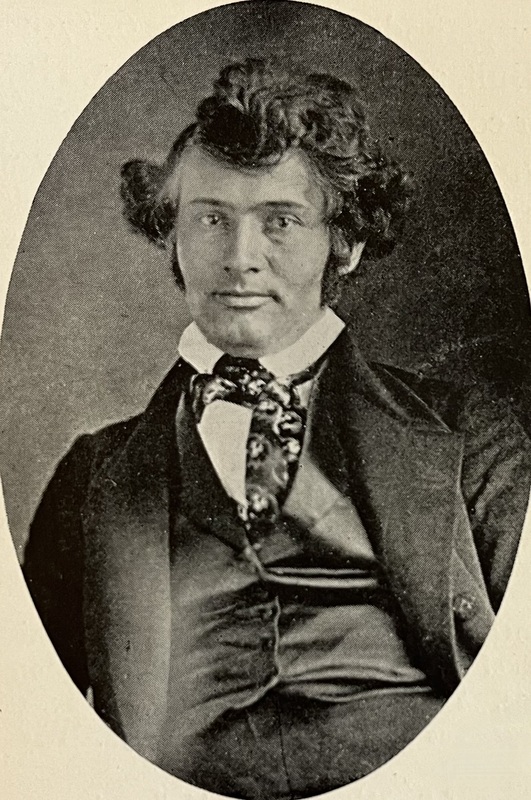

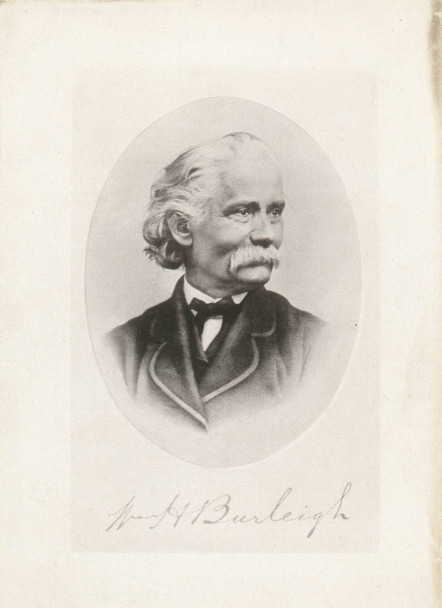

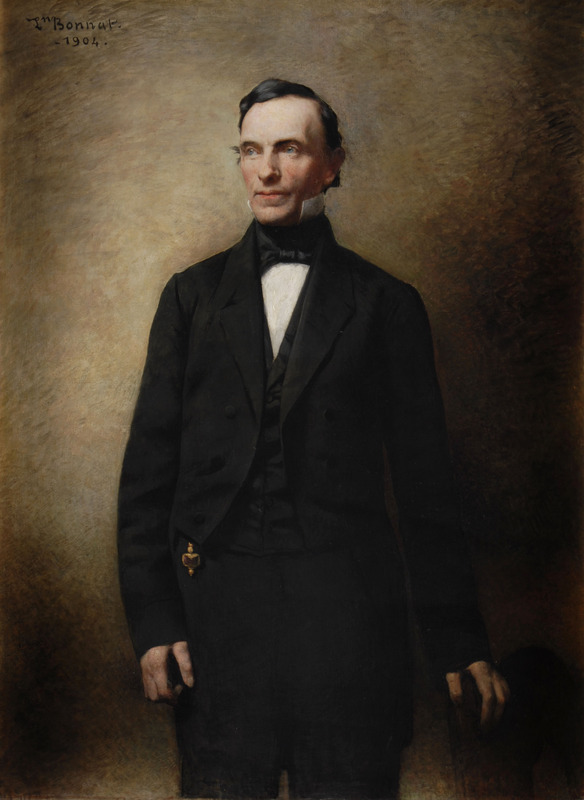

XI. William Henry Burleigh's Personal Appearance

Like his brother Charles, but a bit less notoriously, William Henry Burleigh was not fastidious when it came to his hair or his dress. His reform work was always more important to him than his appearance. This is interesting, because it seems in tension with his finely honed aesthetic sense. In her posthumous sketch of his life, his second wife, Celia Burleigh, notes both the unkempt facts, and the man's rationale.

Here Celia describes the first time she met William, in Syracuse in the summer of 1850, soon after his move to work with the New York State Temperance Society.

"I have met few men who at once impressed me so profoundly, and no picture of the past is more vivid in my remembrance, than his face and figure as I saw him then. His abundant dark hair, undulating in wavy masses, and emphasized by a silver lock on either temple, was worn quite long, and, carelessly thrown back, set off to advantage the square brow and strong, earnest face.

Evidently the arrangement of those locks was no heavy tax upon either the time or the thought of their owner, any more than was the dress, between which and the wearer the relationship was clearly one of mere convenience. "What a pity that he has no sense of clothes!" was my mental ejaculation, as I took in the tout ensemble of what I felt to be an uncommon man. Glancing from the serviceable but not very carefully brushed shoes to the even less carefully brushed locks, my eyes encountered his, those wonderful eyes, which once seen could never be forgotten, — eyes in which the innocence and fun of boyhood, the fire and intensity of manhood, and the tenderness of the poet were blended with a pathetic patience difficult to describe, but which touched me almost to tears. It seemed to me that he must have read my thought, and I blushed at its unworthiness. Years after, when our friendship justified me, as I thought, in expostulating with him on his carelessness in dress, he said, "I should like to dress well, but cannot afford it;" and when I was beginning to explain that it was not money that was needed, at least not much, he replied, "I was not thinking of the money, though that too is to be taken into account, but of all the rest that it costs." "I do not understand you," I said. "Perhaps you have never thought how much besides money it costs to be well dressed. It would cost me an amount of thought that I cannot afford; partly because I have much more important things to think about, and partly because it is a subject of which I know very little, and in addition a wear and strain of temper that I can afford still less. So long as I ignore the whole subject, I am not disturbed by it, but if I once began to think about it there would be no end to my annoyances. The man who is nothing unless he is well dressed is at the mercy of his laundress; losses his temper with his shirt buttons, and feels the waning of his respectability in whitened seams and a lank purse." I mention this because it was so characteristic of the man. With him "mint, and anise, and cumin" never took the place of the weightier matters of truth, integrity, and justice. In his scale the essential values always stood first."

Reference

Celia Burleigh, "Preface: William Henry Burleigh," in William Henry Burleigh and Celia Burleigh. Poems by William H. Burleigh. With a Sketch of his Life by Celia Burleigh. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1871. p. xiv-xvi.

Extensive research is being conducted by members of the Burleigh team on the life, publications, and impact of William Henry Burleigh. In this regard, what exists on this page currently constitutes a bare outline, and snippets - serious and whimsical - of his life and character. Return often, as much more will be added in the coming months and years.