Aesthetics, the Arts, and Social Change

In their published work, and in their private papers, the Burleigh family consistently embraced poetry. Allusions to famous poets of the past were common. As editors, William, Charles, George and Cyrus all drew from the finest American poets of their time. The artist Charles Calistus Burleigh Jr. was also a published poet, though his output was thin.

Poetry was, of course, a more important part of the landscape of expression in the nineteenth-century than it is now. A careful analysis of the poems utilized by the core generation of Burleighs, and their own poetic themes, reveals some interesting through-lines. The most important of these may be in the attention given to William Cowper.

One of William Henry Burleigh's earliest poems (1835) is a well-constructed sonnet on Cowper:

There was a cloud upon his being's sky,

Denser than he might please, which cast a gloom

More fearful than the darkness of the tomb

Upon his pensive spirit. To his eye,

No ray of hope was darted from on high;

He deemed himself predestined to a doom

Hopeless and endless, and a cold despair

Hunk heavily on his heart, and rested there.

Yet holiest affections found a home

Within that heart — and many a plaintive sigh,

Laden with prayer, went upward to that God

Whose chastening is in mercy — and the rod

Was then withdrawn: Death snatched the gloom away,

And poured upon his soul unending day!

(This version published as "Cowper" in The New - Yorker Oct 1, 1836; 2, 2, as part of the "Shreds and Patches" series.)

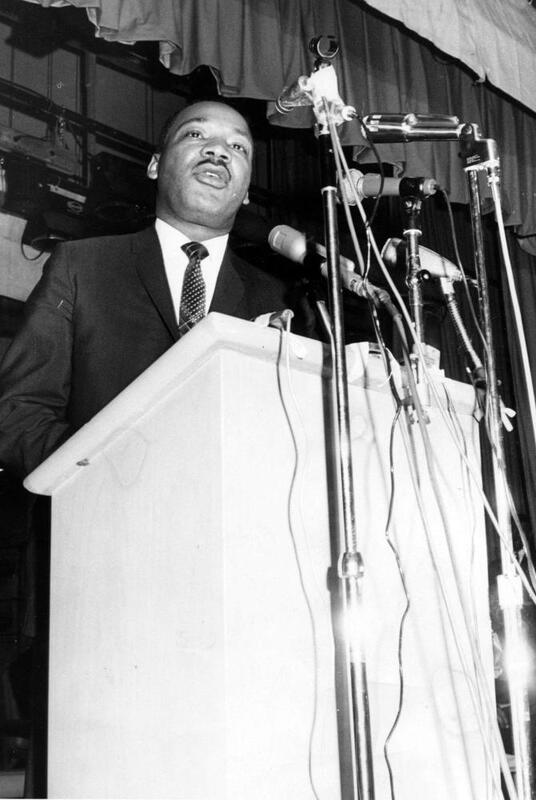

Cowper's influence on Black civil rights continued to echo through the oratory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who quoted the poet in his 1967 speech at Cleveland's Glenville High School. He places Cowper within the context of Black pride, and, significantly, at a high school, Dr. King preached Cowper's assertion that "the mind is the standard of the man."

"every black person in this country must rise up and say I’m somebody; I have a rich proud and noble history, however painful and exploited it has been. I am black, but I am black and beautiful. And so we must be able to cry out with the eloquent poet [Cowper]: “Fleecy locks and black complexion cannot forfeit nature’s claim, Skin may differ but affection dwells in black and white the same. If I were so tall as to reach the pole or to grasp the ocean at a span, I must be measured by my soul, the mind is the standard of the man.” And we must believe this firmly and live by it."

The Abolitionists, including William Burleigh, were among the earliest to grasp the importance of the aesthetic dimension - the way that the words sing in memorable rhythm, the impact of their import extended by their setting, a union of form and function.

We know that Prudence Crandall had a copy of Cowper's work, and obviously William Burleigh had been exposed to him, too. As these two were working with the Black women who came to Canterbury, I can imagine them as teachers sharing these poems with the students. The cross-fertilization of Black and white that happened there helped to build the tradition that still continues today; to quote from the stirring conclusion of Dr. King's speech, "we must keep moving. We must keep going. And so, if you can't fly, run. If you can't run, walk. If you can't walk, crawl. But by all means, keep moving."

In 1843, before the publication of her first book of poems, William Burleigh was in the forefront of American appreciators of Elizabeth Barrett (soon to be Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1806-1861). Writing in The Christian Freeman in one of the first issues he edited, be extols her thus:

George S. Burleigh's conception of the poet's calling is described in a short poem, "Ice Crystals," that is included in The Maniac (1849). It certainly proves him to be a poet in the Romantic tradition, suffused with "delicious pain" and with the self-generated assignment "to bless the earth," but these hopes are swallowed by the final lines and their bitter assessment that the best thoughts disappear before they can be fully expressed:

Ye may have seen, when, on some winter morn,

The first warm breath of home-life, waked again,

Touched with a kiss the cold-cheek'd window pane,

Into what fine and delicate figures drawn,

The keen ice crystals mock'd the viney lawn;

How the sharp shuttles of the invisible frost

Wove their swift shapes of beauty, flower and tree,

Till bough on bough, with foliage intercross'd,

The bright mass grew to thick obscurity.

So with fine thrillings of unuttered Thought,

Clear Beauty trembles through the Poet's brain,

Into fair shapes by its own shrinking wrought,-

His heart-breath crystalized with delicious pain,

Soothed by some silent hope to bless the earth-

Till crowding, form on form, to be borne forth

Into full utterance, all its life is lost;

Stark lies the Beauty in expression's frost,

Frigid, confounded, and of little worth."

Another key poem of George S. Burleigh's addresses his vocation in the 1888 work, "The Poet's Mission." He highlights the political and moral aspirations of both the poet and humanity as central to his work.

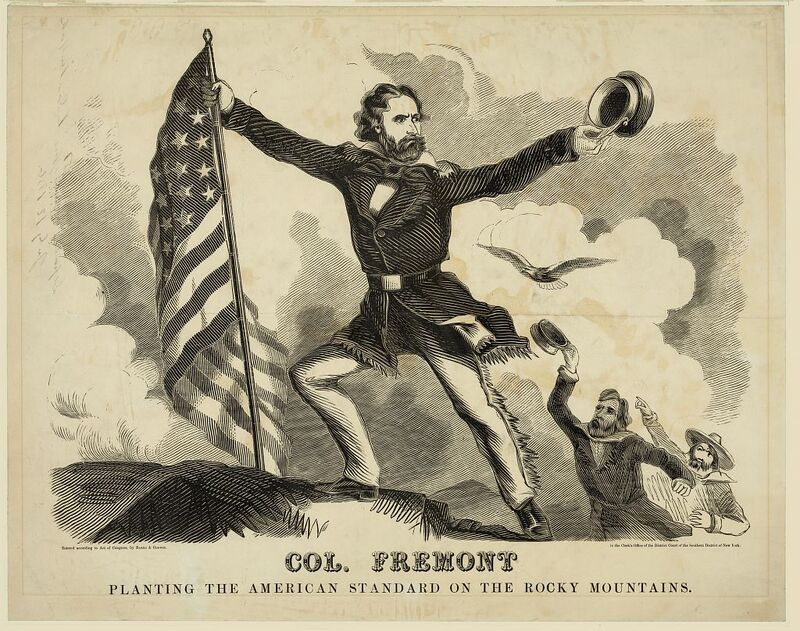

George S. Burleigh wrote copiously in both prose and poetry. His prose works cover children's literature, political literature, and short stores. His poetry included near-epic works, and many shorter works and sonnets intended for the newspapers of the day. He also engaged in translation projects. In 1856, apparently under a short deadline, he wrote a set of poems on the life of Presidential candidate John C. Fremont, the first Republican to run for the highest office. In the preface to this collection - Signal Fires on the Trail of the Pathfinder - George S. Burleigh included a preface that reveals some of his aesthetic theories:

If any open this Volume who have not read some one of the Lives of Fremont, the writer can only desire that they would do so, first of all, and then return to these pages with a witness, which will compel them to confess that poetic enthusiasm has not carried him beyond the record.

The Life of a public man is our possession, for good or ill; and where it seems preëminently for good, as with the case in hand, there is something more than propriety in making use of it.

It is believed that the passing of the momentary interest which has brought the name of FREMONT before us, will not diminish the permanent value which it bears for all, and especially for the young, who are just entering the ranks in the rigid Battle of Life.

These Poems are offered at this time, not only for the perennial excellence of the Subject, but equally for the vital interest of the Moment. The crisis before us is one which puts a new aspect on the whole political world. The Scholar, the Poet, the Plowman, the Man of Business, and the Man of Leisure, have all an interest visibly at stake; and all seem conscious of the vitality of that interest.

No mere political question ever has called out, nor perhaps ever can call out, such an array of combined moral and mental forces, as that which has already taken the field for National Regeneration; and the tide seems only at mid-flood.

If this writer could flatter himself that his effort would in some degree swell the tide-waves of that setting flood, and strengthen the force that would repel the aggressions of Slavery, he could easily forego the hope of a permanent value in his work, or any concern for the criticism of noncombatant friends, who fancy that to crush the aggressive element of Slavery touches not its vitality; as if its very essence was not aggression.

The success or failure of the present movement will not reach the heroic worth of the subject, nor the permanent character of the most of these Poems; where the exigencies of the case have crowded the task of a longer period into some fourteen days — but to our Country the question is of vast importance. The success which Freedom has a right to expect, at the hands of her lovers, will be the turning-point in the long history of her disasters — henceforth to become the story of her steady and unceasing progress toward perfect victory.

In the faith that such is the crisis, and the hope that these gleams from a noble life may add one ray to the new dawn, they are flung out, and committed to their fate, by The Author. (p. vii-viii)