Items

-

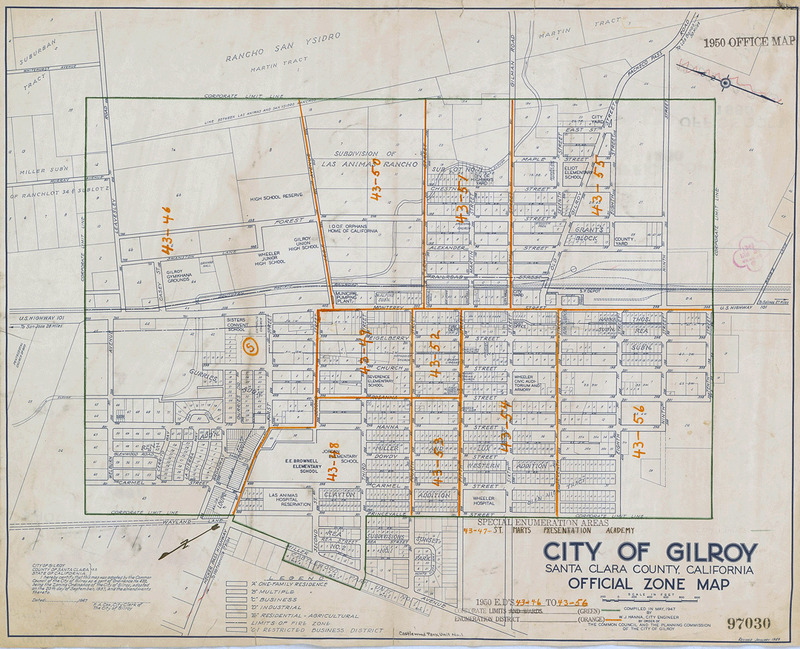

The Gilroy Colonia, WWII-1960During the Spanish colonial era, two land grants (Rancho Las Animas and Rancho San Ysidro) comprised what is now the region known as Gilroy. Additional land grants were issued during the Mexican era. The city of Gilroy was eventually named after a Scottish immigrant, John Cameron, who came to Monterey in 1814 and changed his name to Juan Bautista Gilroy after converting to Catholicism. He worked on Rancho San Ysidro, marrying the ranchero’s daughter Maria Clara Ortega, and became a naturalized Mexican citizen. Eventually he inherited a part of Rancho San Ysidro and raised cattle. During the American Period, Gilroy incorporated as a town (1868), and most of the Mexican rancho land passed into the hands of Anglo farmers and ranchers. In the late 1850s much of Rancho Los Animas (12,000 acres) was sold to Henry Miller, a famed cattleman in the Miller & Lux Company, which lobbied for the railroad to run through Gilroy in order to facilitate their cattle raising/butchering operations. The area boasted prune, cherry, and apricot orchards, with the producer exchange Sunsweet overseeing the drying of these crops for market. In the early 1960s, orchards were replaced by row crops of tomatoes, sugar beets, and garlic. Prior to WWII, Mexican immigrants migrated to work in the orchards and fields, living temporarily on the ranches where they worked. Some Mexicans, such as the García family who migrated from Texas, began moving into Gilroy during WWII. They initially bought a large apartment complex, the Guadalupe Apartments, on Eigelberry and 7th Street, and then opened the Post Office Market on 6th Street and Monterey Road, which they sold and then established García (card) Club in 1952 on Monterey Road between 6th and 7th Street facing the railroad. The Mexican businesses of the García family were unique. Gilroy was a small town, so there was not a separate Mexican business district, and Mexican residents did not attend separate schools or theaters. Instead Wednesday was “Mexican Night” at the Anglo-owned Strand Theater, with headliners such as Cantinflas appearing on occasion. It was not until WWII and later that Mexicans moved into higher paid, unionized cannery work. Though still seasonal, it was flexible enough to allow workers to move to other jobs when necessary. Employment at the Felice and Perrelli Cannery (1914-1997) enabled several generations of Mexican families to establish roots in town. The Gilroy Mexican Colonia appeared south of 7th Street, with some settling on the westside of Monterey Road and the majority living east of Monterey Road next to the canneries and railroad tracks.

-

The Mountain View Colonia, WWII-1960The Hispanic roots of Mountain View stretch back to the Mexican land grant of Rancho Pastoria de Las Borregas of 8,800 acres that included lands in current Sunnyvale and Mountain View, granted to Francisco Estrada and his wife Inez in 1842. When the Estradas died in 1845 they left their land to Inez’s father, Mariano Castro. Castro sold the eastern half of the rancho, what is now Sunnyvale, to Irishman Martin Murphy, Jr. Murphy had arrived in 1844 and planted Santa Clara County’s first orchard on his newly acquired land. Castro died in 1856, leaving the Mountain View portion to his son, Crisanto Castro. Like other Mexican Californios, the Castros fought in the American courts from 1852 to 1871 to validate their land grants but lost most of it to squatters and lawyers fees. The Castro family remained in Mountain View until 1958, when they sold their remaining 23.5 acres to the City of Mountain View. In the early 1900s Spanish immigrants arrived in Santa Clara County. Many who had worked in the orchards and canneries in the 1920s and 1930s moved to Mountain View, California, settling in the northern section of the city above the canneries, packinghouses and railroads. These included the Mountain View Fruit Packing Company, Clark Canning, and San José Fruit Preserving Company. Around 1920, the P.L. Sanguinetti Cannery in Mountain View was acquired by the Richmond-Chase Cannery, one of the largest in California. Sharing a common language, the Spanish community welcomed Mexican immigrants who arrived in Mountain View during and after WWII. This would eventually transform the Spanish neighborhood into the Mountain View Mexican Colonia. In such a small town, Mexicans did not form a separate commercial district but melded cultural traditions and a shared language. St. Joseph Catholic Church became the heart of the Colonia, and during the late 1940s to 1950 Father Donald McDonnell encouraged the Mexican community to address their financial, economic, and social needs by creating Club Estrella as well as a community credit union. Club Estrella hosted annual church and community events for the entire Spanish speaking community. Increasing urbanization and highway expansion during the 1950s and 1960s brought major thoroughfares through the heart of the district and decimated the established Mountain View Colonia. Father McDonnell was assigned to the Mexican mission in Eastside San José in 1951, and helped establish the San José de Guadalupe Church and became a mentor to César Chávez.

-

Cannery DeclineAt the height of the fruit season during WWII, canneries operated seven days a week with shifts as long as eleven or twelve hours per day. After World War II, demand for canned fruit rapidly declined, leaving owners holding large loans that had been taken out to expand productivity. Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, orchards and fields were being replaced by business and research parks and housing developments, creating the emerging Silicon Valley. Changes occurred also when the Teamsters Union took cannery representation away from the AFL, and when Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1967) required that jobs could not be classified as “male” or “female” work. By 1976, because most cannery jobs were unionized, women were receiving wage, medical, holiday, and retirement benefits. Although their benefits were still lower than men’s, women found cannery work offered stability, allowing many to become homeowners. When fruit processing operations began to decline in the 1970s, the growth of manufacturing in the electronics industry and new housing tracts provided opportunities for displaced workers in construction, railroads, warehouse, and assembly work. Unfortunately, these new jobs were not comparable to the higher-wage union jobs in the canning industry. For many workers, the cannery closures meant the end of secure jobs with benefits and the long-term working relationships they had created. By 1987, only eight canneries existed in the valley, the era ended when, in 1999, Del Monte closed its largest cannery, Plant #3, the site of the 1893 San Jose Fruit Packing Company.

-

Women's Double Work DayCannery women were also faced with the double work day, often working full time or overtime at the cannery while still expected to care for the home and family. Still, most considered cannery work a better alternative than field or orchard jobs. Working seasonally enabled them to supplement the family income or serve as the breadwinner when husbands were unemployed, while maintaining their primary roles as wives and mothers. A major challenge for cannery women was finding appropriate and affordable childcare. During the 1940s and 1950s, CalPak operated a nursery at the Del Monte Plant #3, providing childcare during the day and second shift. However, as childcare was unavailable at most canneries, mothers left their children with family members or neighbors, while others paid for babysitters or bartered for care with co-workers. Husbands and wives who worked at the same plant might arrange complicated shift schedules. Working mothers believed that, in easing their husbands’ responsibility as providers, they could ask for more assistance with housework. However, men often found it difficult to participate in many of these domestic chores, so cooking and childcare were often handled by older children. Women cannery workers knew that their paychecks enabled them to provide more assistance to their children, send their kids to college, allow their husbands to attend trade school, start their own business, or have a higher standard of living, and they wanted a say in how household money would be spent. Women made time to do the necessary household chores by extending their day, staying up late or waking early.

-

Cannery Injuries and HazardsBefore the 1930s, workdays for women cannery workers could be up to 18 hours, or 96 hours a week. Historian Glenna Matthews notes that in 1913 the Industrial Welfare Commission was formed to protect laboring women and children but excluded workers in “perishable materials” such as cannery workers. A high percentage of women working in canneries at that time were immigrants who spoke limited English, so receiving adequate training was difficult, and safety instructions were printed only in English. Assembly-line labor was repetitive, and women stood at their stations for hours working with their hands in acidic fruit. Many women reported severe damage to their hands and fingers from operating swiftly-running machinery. Many reported severe damage to their hands, not from traumatic injuries but from nicks and cuts received while cutting fruit by hand. As cans rattled along conveyors in buildings that were sometimes the size of four football fields, noise was also a constant problem. Industrial chemicals were hard on the skin and a hazard to eyes and lungs. At the peak of the season, workers might put in ten hours a day, six days a week, leaving them exhausted and dehydrated at the end of their shift. Women continued to bring health and safety concerns to management and their unions. During and after WWII, some larger canneries, such as Del Monte, created an infirmary with a nurse near the processing line. While conditions generally improved over time, anthropologist Patricia Zavella, in her book Women’s Work and Chicano Families, noted that in 1978, canneries were still considered one of the most dangerous industries, second only to lumber manufacturing according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

-

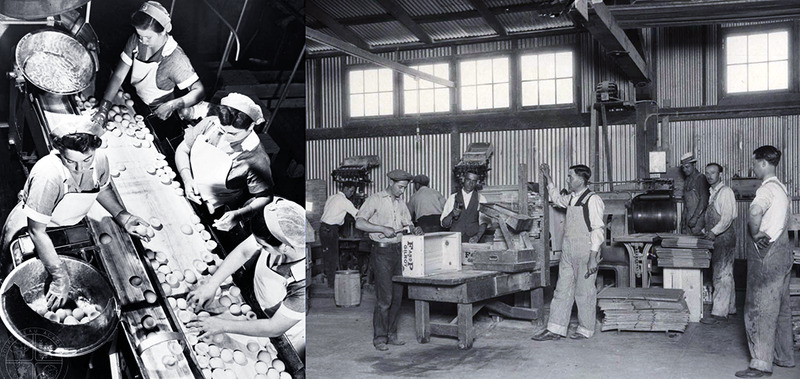

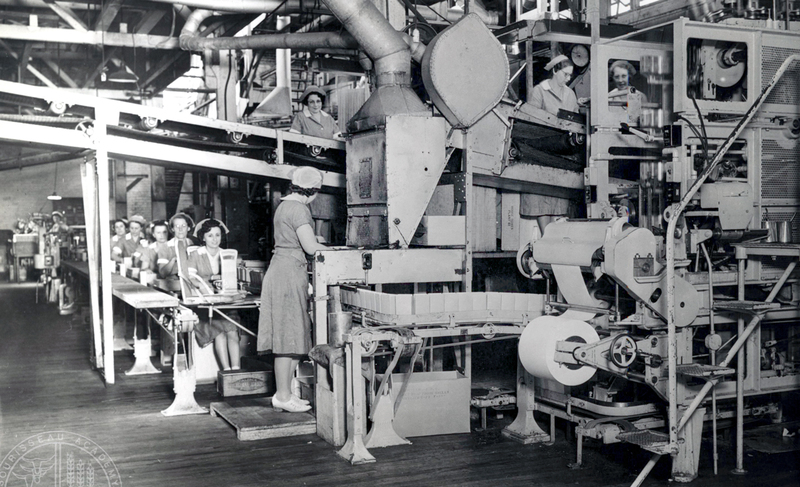

A Day on the Cannery Assembly LineBy the 1950s, many operations formerly done by hand were now at least partially performed by machines. Fruit arriving at the cannery, such as peaches, was dumped onto “shakers”; then onto the conveyor belt for cleaning, washing, pitting, and halving by machine; and finally sorted into grades by hand. A few women supervisors oversaw this female-dominated task. On the floor, workers stood at their stations sorting fruit as it came down the conveyor. Cans on conveyors filed by the seam-inspectors, and women “checkers” sealed the cans before they were loaded into cookers. Women concentrated on doing their jobs quickly in order to meet required quotas. Processing areas were noisy, with the constant clamor of machinery and cans running along conveyor belts. Chemicals such as lye and chlorine were used to wash and clean the fruit. Some women who worked in steaming and canning spinach complained of their nails falling off due to prolonged submersion into the spinach vats. Fruit and vegetable processing required a great deal of handwork to sort, weigh, and fill cans with sometimes steaming hot produce. Once canned, some women looked for dented cans before they were boxed up. The work was demanding and exhausting, constantly proceeding at a pace set by the conveyor belt. When the women got home, their bodies smelled like the fruit or vegetable in which they worked all day, particularly tomatoes. It was difficult to get adequate rest. Many women cannery workers complained about hearing the clanking of the machines even in their sleep. By the 1940s, shifts usually lasted eight hours but could be longer during peak harvest periods, when some canneries operated on a 24-hour schedule. Companies facing labor shortages encouraged regular employees to work overtime, and despite the demands of the job, many welcomed the opportunity to earn extra money.

-

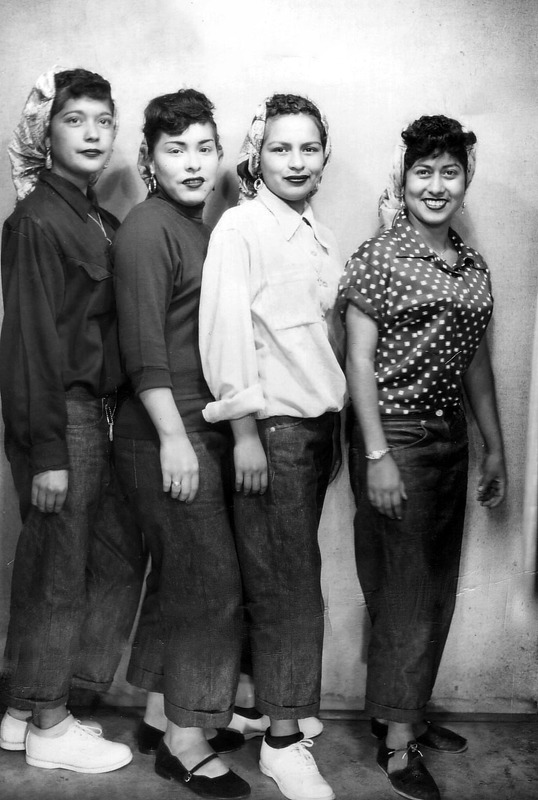

Women's Work CultureMany women found jobs in the canneries through other family members who worked at the same plant. Since little job training was provided, family members could offer advice on the use of equipment as well as how to work with supervisors. Lunching together, sharing babysitting, or traveling to work with family members strengthened kinship networks, and new friendships developed with people they may not have met outside the cannery. Unlike the men who worked in shipping, warehousing, or as equipment operators, before 1970, women did not view cannery jobs as a permanent occupation because there were few opportunities for training and advancement. Women workers, no matter their background, shared mutual concerns about wages, working conditions, and poor supervisors. There was no time to socialize while on the assembly line or during brief breaks, and the noise made it hard to converse. In the 1930s, shared concerns over workplace safety and low wages led some Mexican women to become involved in union organizing efforts, including strikes, and to rely on social networks for support. “Women’s cannery work culture” made the daily routine easier because women shared their experiences, helping each other adjust to the challenges of the workplace.

-

Ethnic and Immigrant Division in Cannery WorkNot until the 1940s were Mexican women born in the United States, fluent in English, finally able to advance to office work or supervisorial jobs. Prior to that time, line supervisors were typically Italian or Portuguese, while crews were overwhelmingly Mexican. Supervisors held a degree of authority and could dismiss workers at will. Forewomen circulated the shop floor, enforcing rules, instructing workers, and pushing for faster, more accurate work. Most importantly, forewomen had complete discretion in assigning workers. While ethnic white women might do the same jobs as Mexican women, they were often segregated by their supervisors, who sometimes helped members of their own group secure better jobs. Combined with the language barrier, Mexican women found little basis for solidarity with these co-workers and sometimes perceived comments from supervisors as racially biased. In addition, although they all might speak Spanish, relations between American-born Mexicans and Mexican immigrants could sometimes be strained.

-

Gender Division in Cannery WorkIn the canneries up until the 1970s with the implementation of the 1960s Civil Rights legislation, men held year-round jobs in shipping and warehouses, with women assigned to “semi-skilled” seasonal assembly-line hand labor–peeling, cutting, and slicing–standing at work stations all day except for lunch and breaks. Most women were assigned to processing operations or “women’s department.” The monotony and boredom of assembly-line work was a strain, unlike men’s jobs, which allowed for more independence. Cook-room, labeling, stacking, and boxing machines were generally operated by men, who also managed the storage and shipping warehouses. Under the assumption that they were better suited for physical labor and were supporting families, men were assigned to the higher-paying work of supervising, heavy lifting, and equipment operation and maintenance. Full-time jobs provided higher wages and opportunities for advancement, along with a degree of autonomy. Due to these gendered job categories, women also suffered from limited opportunities for advancement. Not until the 1970s, after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, would they move into higher-paying, year-round jobs traditionally reserved for men.

-

Seasonal Work and the Shape-UpFruit and vegetable harvests are seasonal and must be processed immediately to ensure peak quality. Large canneries with access to produce from other regions might shift from one product to another, operating year-round. During harvest season, canneries operated around the clock, with three shifts of workers per day. While some workers returned annually, new employees were hired seasonally through “shape-ups,” an informal selection process in which workers gathered in front of the office hoping to be hired at the cannery. Due to the large number of canneries and packing houses in the county, workers usually had several opportunities to find work nearby. During labor shortages, canneries in Santa Clara County advertised in Bay Area newspapers to ensure at least a minimum number of applicants. Having a connection in the cannery workforce–friends or family–often resulted in a hiring preference, and these ties were also helpful on the job as experienced workers provided support and instruction to newcomers. Because employment was seasonal, workers maximized income while jobs were available, working daily and often overtime. This might mean hiding a pregnancy (because pregnant women were not hired), working when sick, or staying on the job even after an injury. Workers wanted to make sure that they would be asked to return for the next season.

-

Mexicans Move to Cannery Work During and After WWIIWWII was a profitable period for growers, packers, canners, and workers as destruction of farmland in Europe and the mobilization of the military worldwide generated a huge demand for canned goods. Over half of Santa Clara County canning production was allocated for the war effort. Meanwhile, canneries in San José suffered labor shortages because of the absence of men to the military and the shift of ethnic white women to higher-paying, year-round “Rosie the Riveter” manufacturing jobs, such as at Hendy Iron Works. In response, Mexican women and braceros filled cannery jobs. During peak periods, canneries operated non-stop, and many provided transportation during the night shift or allowed women to work until 6:00 a.m., when public buses began to operate. From 1948 to the 1970s, among cannery women workers, Mexicans comprised the largest ethnic group, with Mexican women working on the line under the supervision of older Italian and Portuguese women, while Mexican men worked in the higher-paying year-round warehouse jobs. Second-generation, English-speaking Mexican American women moved easily from the cannery line to higher- paying supervisory positions and front-office jobs.

-

Women Dominate the Ethnic White Cannery Labor Force Pre-WWIICanneries are labor-intensive operations, and the labor force required to serve this expanding industry grew with the increase of orchards under production. Jobs were clearly divided along gender, ethnic, and racial lines. Chinese men, Mexican Californio women and men, and Anglo men and women filled the first cannery jobs when the canneries during the 1870s and 1880s. Following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish immigrants soon dominated the Santa Clara County cannery labor force into WWII. By the 1930s, Santa Clara County’s 38 canneries were the largest employers of women in California. Historian Glenna Matthews divides these canneries into three categories: the large corporate canners of Libby’s, Hunt’s, or Calpak; the smaller joint firms such as Richmond-Chase (2,073 peak season workers); and the marginal single canneries, including Garden City Canning Company (197 peak season workers). In the 1930s, white ethnic women had risen to supervisory positions as floor ladies, with full authority over subordinates. During WWII, many of these women moved to better paying positions in defense industries and jobs vacated by men. By the mid-1940s, the percentage of women in the American workforce had expanded from 25 to 36 percent. With the wartime labor shortages, more Mexican women were recruited to work in the canneries.

-

Formation of Producer Exchanges in Santa Clara CountyCanners and growers formed producer exchanges or cooperatives in which groups of farmers producing the same type of crop collaborated to negotiate prices, hire labor, and access larger markets. In agriculture, these exchanges were characterized by ”horizontal integration,” in which companies of the same industry band together for harvesting, processing, and selling. Just as in Southern California citrus, Santa Clara County canners and growers formed a producer exchange in 1899. San José Fruit Packing Company (SJFPC) joined with seventeen other companies (including half of the canning establishments in California) to form the California Fruit Canners’ Association (CFCA), which eventually operated 28 fruit and vegetable canneries through the state and acquired operations in four other states. Within four years, CFCA was the world’s leader in fruit and vegetable canning and drying. By 1916 the CFCA had merged with five other canneries to form California Packing Corporation (CalPak), developing into the Del Monte Brand, the first national company in the United States, offering 50 products. Cannery operations were large facilities, with warehouses, processing facilities, railyards, garages, shops, and offices, employing several hundred to several thousand people. As a regional hub for the food processing industry, local canneries received produce not only from the Bay area but from much of Northern and Central California. Historian Glenna Matthews states that by the 1930s Calpak was the largest canner in California and Santa Clara County had become the fruit processing capital of the world. This photo shows women packing prunes at Calpak Plant No. 51 on Bush Street, south of The Alameda.

-

The History of Cannery Development in Santa Clara CountyFollowing early experimentation with horticulture, the canning industry was established in 1872. Aided by an expanded railroad system and access to broader markets, Santa Clara County became the capital for fruit processing/canning. In 1920, the county produced 90% of California’s canned fruits and vegetables, a share that continued into the 1950s. Increased mechanization and more efficient processes gradually replaced most of the hand labor in the canneries. The construction of new packing houses and canneries west of the Guadalupe River, north of Jackson, and south of Keyes Street drew migrant ethnic Mexican laborers into those areas of San José. Early promoters called San José “The Garden City.” To take advantage of bumper crop years, keep their product fresh after the season, and utilize distant markets, orchard ranchers preserved their fruit through canning and drying. In 1871 at his home on The Alameda, Dr. James Dawson, a local doctor/fruit grower, formed Dawson & Company, which In 1875 was renamed the San Jose Fruit Packing Company (SJFPCO), located at the corner of Fifth and Julian Streets. In 1893 the company, relocated to the west side of the Guadalupe River south of Auzerais Street, was the largest cannery in the world. By 1900 canned food production had become the second largest industry in California, with Santa Clara County in the lead. During the 1930s, 38 canneries hiring up to 30,000 people at peak season operated in the county, several run by huge corporations such as Libby’s, Hunt’s, Richmond-Chase, and Calpak. Commercial sales of fruit increased with the construction of the San Jose Fruit Packing Company facility in 1875. Workers at the first canneries included local residents and seasonal migrants. Some employers offered company housing for skilled workers, though individually rented boarding house rooms and hotel rooms were more typical. Worker neighborhoods with small family homes soon appeared adjacent to packing houses and canneries. San José's Eastside grew after the Mayfair Fruit Packing Company was constructed in 1944, in the largely Mexican neighborhood known as the Mayfair district.

-

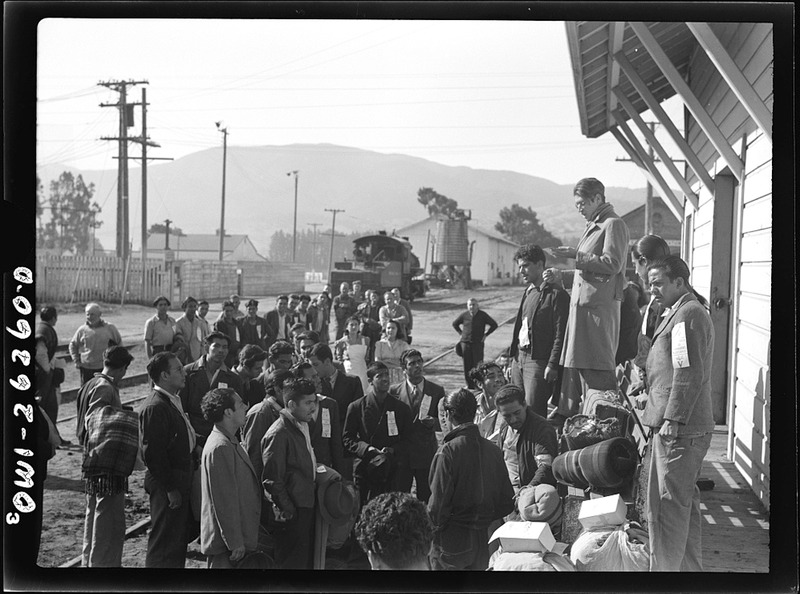

Bracero Farm Work and HousingWorld War II became known as California’s second gold rush. Growers turned to the federal government to help fill the labor gap created by military enlistment and government military contracts, which were not open to Mexican workers. The 1942 Emergency Farm Labor Agreement signed by Mexico and the U.S. sent thousands of braceros (men who work with their arms) across the border to fill lower-paid, seasonal agricultural jobs. The war-time emergency program lasted until 1964 and deterred any successful agricultural unionizing efforts undertaken by Mexican farmworkers during WWII and after. By July 1945 more than 58,000 braceros were working in agriculture (cannery and farm work), with almost 62,000 on railroad crews. At the peak harvest season of August 1954, there were 1,000 braceros employed in Santa Clara County. According to the transnational agreement, bracero workers were not to undercut local domestic labor and were to be provided with adequate housing. It was up to the Mexican consulate to inspect bracero living and working conditions. In California, with Mexican consular offices only in Los Angeles and San Francisco, it was difficult to monitor the program and enforce the terms of the agreement.

-

Orchard vs. Field/Row Crop Work QuotesMy mom was working at the camp. She had to keep track of the kids. There were probably a half dozen little kids there. [The rest of the kids worked] with my dad. If you can carry a bucket, and you can pick a prune, you were old enough. In the 1940s, there were no regulations.If you wanted to bring your five-year-old to pick prunes, you could take him. Nobody said anything. [We would start at] seven o’clock in the morning. My mother used to make tacos and send them to us ‘cuz we weren’t too far from the camp. [We’d] work until five o’clock at night. InSouthern California [citrus], they would shake the trees and [but in Santa Clara County you would pick prunes off the ground… You would put them in a bucket, then you fill the boxes. They [the prunes] would fall and get pieces of dirt in them and get a little damaged. So you had to be on your knees, or one knee, whichever way you could. If you had a child, he’d have a little bucket. The full buckets probably weighed thirty pounds. Some mothers picked prunes, whole families, men, women, and children. Everybody picks prunes. Here in San José ,you would pick apricots off the tree. If it falls off you don’t pick it because everything here went to the canneries. Here in San José, when you picked apricots, you had to carry your own ladder,[wooden ladder]. They didn’t have aluminum ladders like they do now. Fernando ChavezInterview by Dr. Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Peggy Wallace, Feb. 6, 2008, Cupertino, CA. In the summers, we went to the San Joaquin Valley from San José to work. I started at 6-7 years old picking cotton. Well, you had to get up at four in the morning ‘cause it’s too damn hot in the [San Joaquin] Valley. I mean by noon you’re already at 105, 110. So we’d get up early… So my mom would have her sack, and I’d have mine, and my younger brother Jim, would be with my mom’s sack, we’d pull him, and my other brother would be with me. He was more sickly than my other brother. He had asthma, he had eczema, and things of that nature. So we used to drag him ‘cause it was dark when we were out there picking. The only thing…they’re out picking cotton and you get the little things stuck in your fingernails and stuff. We tried to wear gloves, but it was hard because you couldn’t feel the cotton to pick. When we would go to Wasco, we would stay with my grandfather. He only had a one bedroom house, and so it was a house full of people [laughing]. Besides my grandparents, there were two other families. My aunt Alice and her kids, she had six, and then my brothers and I and my mom. We would take mattress outside and sleep out in the front yard. It was so hot, and there was no air conditioning. Their big thing was to get what they called “swamp coolers”. You used water to cool off. There was no air conditioner, that was the air conditioner in those days. I remember going and dumping all the cotton and weighing it, they weighed it before they dumped it. My mother would take the money we made. And I graduated from cotton to picking grapes in Del Rey with an uncle of mine. Coming back to San José, it was always prunes, mostly prunes, apricots, and then pears. It’s hot [laughs] and, well, the first thing you learn as a farmworker, you ask in terms of pay. Okay, how are you going to pay me? By the bucket, the box? What got me out of the farmwork was, I was probably about twelve, thirteen years old, we went, my mom and I, we had an aunt and uncle that were across from the old IBM building, across from where my grandfather had his ranch. My aunt and uncle were foremen on a ranch, and my parents left us there for the summer. So, when the owner came, I was asking, ‘How much are you paying us? Well how much would I get for picking a ton of prunes?” He looked at me [surprised]. “Yeah, you’re gonna pick a ton of prunes…” He gave me some number, and I said “Oh, okay.” Well I picked a ton of prunes. But when he put that money in my hands, I’m looking at it going, “Wait a minute. A ton of prunes. No, this doesn’t equate.” It was like seven dollars or something like that. But that’s what it was like… When you’re picking prunes, or you’re picking anything, you couldn’t wait to get closer to the road. Wherever you were working, to get closer, to see what people were driving. That there were people driving nice cars, or doing something you couldn’t do. I couldn’t be out there going on a luxury drive or whatever. But then you’d come back away from the road, because you’re working in rows, particularly with fruit or vegetables. Richard Vasquez Interviewed by Dr. Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Margarita Garcia Villa, Dec. 21, 2016, Watsonville, CA In the [San Joaquin] Valley…when I was nine, [my family] used to stop like in Mendota and chop cotton. Then we would do apricots and prunes [in San José}. And then after that they’d go back and pick cotton and they did grapes [in the San Joaquin Valley] and they went back and forth from Fresno [to San José]. I was born in 1934. In them days you had to work as soon as you started walking, you carried your sack for picking cotton. We thought it was fun. We had a potato sack. My dad used to buy…. one hundred pounds of beans, one hundred pound of potatoes, and that was for the winter to eat. We lived in Firebaugh, when I was five years old, and that’s when I remember I used to pick cotton….Because when that the cotton grows in a ball like this, and then when it starts opening up like that, it has like [sharp, pointy] stickers right there, and when you go get the cotton, that’s what gets your fingers right here [stabbing you]. My dad always had a car. In Fresno we used to live under trees all the time, in tents. My dad always had like three tents. I remember one year…that was in forty-one, in this one camp…it was raining all night…By then we had cots, army cots… One of my brothers and I used to sleep on the same little cot, and then when they said, “Time to get up!” We were going to get up and I looked down and there was like about a foot of water. When we came [to San José], my dad used to make four walls out of the apricot trays. [The growers would] dry the apricots on the trays. [My dad] used to tie them up with wire and make the walls. And then like on one side he would leave an opening like a door. And the boxes, the fruit boxes, those were the cabinets. The growers didn’t provide housing. We used to work up there in Evergreen [in San José]…The growers grew apricots and prunes. In apricots we used 8 foot wood ladders that weighed 35 or 40 lbs, you carried from tree to tree. You put your hand through one of the steps and you drop the ladder like this, and then you just carry it [to the tree you are picking]. You carried a metal bucket that weighed five or ten pounds… Now you climb up… and you pick [the apricots] with your hands… They’re real small, and they’re real soft. Say a branch is coming up like this, and you hang the bucket on the branch, and whatever is hanging around that branch you can just [put in the bucket]. And then when it gets too heavy you put [the bucket] on the ladder and then you start picking. [When full, the bucket weighed] I think forty-five, fifty pounds. They get pretty heavy. They wouldn’t let me pick them until I was twelve…thirteen. [In apricots, you dump in boxes, then women would cut them, take the pits out, and put them] on wooden trays to dry. The trays were about 8 feet long and 30 inches wide…First what they do, they stack them, …about five feet or six feet high. But five feet mostly. And they have little spurs, little rails [to put them on], and they have little cars that they used to push them into what they called a smoker, a dryer [or shed]. And then they put sulfur and then they burn the sulfur. And then they push the car, the little cart in there with the trays and everything. They’re all still stacked, and then they close the doors, and have them sealed so no smoke comes out. So that’s the way they cure them. And the next day they pull that out, and then they have men that spread [the trays] out…They leave them there for days until they are dried out. [With prunes], if you were three years old you could pick. Anybody could walk in, [and pick them] right off the ground. Most of the time apricots and prunes start in the last days and weeks of June. Walnut season goes through July, August, September. Like the last two weeks of August and then all through September. A lot of times we used to pick walnuts three times. Like we had to wait for whatever dropped by itself. And the second time a lot more fell down by itself. On the last one we have to shake the trees. They give you a long stick with a hook on it, and that’s what they call the shakers. You shake the tree. You knock everything down. In Fresno, in walnuts, we had to pick by hand and put into boxes. Before, they used to have small boxes, you know like…about ten inches high, and they’re about fourteen inches wide…and about thirty inches long… We used to fill them up. When we did it with my dad or with my brother, they used to put about six boxes together, and we just went and dumped [into] them. Because that way you wouldn’t be wasting time to wait for somebody else to dump it. We were pretty smart. You work with just the family… When I was older, like sixteen, fifteen or sixteen, I used to go with my brothers and my sisters. There was a lot of families, so you just took one row. You just went on that one row or you took two rows, and that belongs to the family. And everybody between the trees, you couldn’t go on [the other family’s] side, …that was your tree, your side. You couldn’t go on that side or else they’ll be throwing rocks [at you]. My dad always built a fire [at lunch time], yeah. No matter how hot it was. I remember sometimes [in the San Joaquin Valley] he was picking grapes in the summertime and it was real hot, like right there in Sanger. My mother always made, now we call them burritos, but in them days they were tacos. Tortilla tacos, and she used to make a big pot of them, and they were always wrapped in cloth, and they were still warm by twelve o’clock, the time we were going to go eat. They were filled with beans, rice or potatoes. Whatever there was. Most of the time there were just Mexicans [we worked with]. The only time I saw other people, white people and black people, I was already seventeen, was when I went over there in Los Banos. We were picking cotton, and they used to bring people from Oakland, a bus of white people and a bus of black people, in the 1950s. Where they worked different, it was when I was like six years old in the 1940s, we lived in a camp in Firebaugh, in a camp they called it Giffins, that must have been the name of the owner or something….They had a reservoir, and then the water used to come in from there, but there was a bridge. And only white people lived on one side, and all the Mexicans on the other side. That divided everybody. And you couldn’t go on that side, or you couldn’t go pick where they picked, they picked in different places. That was in cotton. Herminia and Leandro Villareal Interviewed by Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Joseph Rivera, Nov. 12, 2005, San José, California

-

Orchard vs. Row Crop/Field WorkDuring the 1920s and 1930s, Mexicans performed 80% of the harvest work in Santa Clara County. Racially and ethnically segregated workplaces were the norm in orchard and row crops, with each group working either a different crop or at a different skill level and getting paid different amounts. Anglo male farmworkers filled the skilled year-round work of pruning and irrigating, while Mexican immigrant workers were forced into seasonal harvest jobs. Mexican workers labored for at least ten hours a day, seven days a week during harvest season and were paid on a piece-work rather than hourly basis. With the introduction of specialty crops in the late 1800s, only male workers were hired; however, employers soon found they could attract and retain workers if they employed men with families. Between 1920-1940 first-generation Mexican immigrant men and children, who began work at five or six years of age, often worked as a group, with only the father paid for his entire family’s labor. Mexican immigrant mothers stayed at home to care for their babies and campsites; women did not enter cannery work in Santa Clara Valley until World War II. Child labor laws (covering minors under age 15) were not created until 1938 when Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which was not enforced until after WWII. The federal Fair Employment Practices Committee, established by the Roosevelt administration in 1941, found that more than one-third of all complaints came from Mexican agricultural workers.

-

Mexican Migrant Housing QuotesWell, they didn’t have houses. Most of the Mexicans had their own little tents that they brought along with them, living in their car. All the tents hanging off the cars, just like you see in THE GRAPES OF WRATH. They really had big cars because they really needed them—even though they were more expensive to keep up. There was very little eviction because they didn’t live in any place. They had their own things with them, just like a snail would; you carry your own shells with you. They could take the tents off the land, when people said you have to get off the land. Because if you came to pick peas, you generally camped on the land that the peas were on. Elizabeth Nicholas (1930s CAWIU Santa Clara Valley cannery union organizer) Interview by Margo McBane, 1970s, MountainView, CA. We went to Santa Maria, and my dad bought a tent and he made a great big bed. The whole family slept on that one big bed…. [We had our own stove] and my mother was good at [setting up the tent]. She would get the boxes that they used to pick tomatoes and prunes and she would just stack ‘em and make shelving. And she’d cook outside. Sid Duran Interview by Margo McBane, Oct. 3, 2011, San José Chapter GI Forum Headquarters We were 13 kids. And we used to go pick apricots in Saratoga. There’s a street, it’s called Cox Avenue. And we picked prunes for Ed Cox. So when he brought us, he would just tell us, “Okay, you can camp in that bare area there”. He had one outhouse and one faucet sticking up from the ground, and everybody got water from that one faucet. And some people brought tents. [My mom and my granddad] had a tent, and so we used it. At that time, on the beds there were no box springs and mattresses like we have now. They were the bare springs, and the mattresses were the cotton… that you would roll up. So, we would take our beds from the home and we would roll them up and tie it with a piece of rope. Tie each end and throw them up in the truck, four of those or as many as we needed. We didn’t bring food because when we got here we would ask Ed Cox to advance us some money so we could go to the grocery store and buy food. And so my mother would pack most of the stuff in about three old tin bathtubs that had holes in Them…that are small at the bottom, wide at the top… [When we got to the campsite] First of all, we would get some apricot [and prune] trays and stand them up and tie them with wire and… make two rooms. [Then we would take more trays] and make a platform upside down and unroll our mattress on that. And my mom and dad slept on one side,... [And the 13 of] us on the other side. My dad would make a mound of dirt and maybe two feet wide and eight inches high. He would [take one of the three old tin tubs] turn it upside down on that mound of dirt just to elevate it a Little bit. He would cut a hole on the side of the tub and that was my mother’s stove…. When we bought food, we always bought a hundred pound sack of flour and a hundred pound sack of beans…we couldn’t go to a store and get milk, my mother always bought canned milk in boxes… My mother would then make tortillas, probably at least twice a day from scratch. She would stand up a hundred-pound sack of flour and open it up. Then she would get a pan, maybe six or eight inches deep… She would make the dough by hand. She knew exactly how much water to put in it and a little salt and baking powder. She had done it millions of times. In five minutes she would have enough dough to make three or four dozen tortillas by hand. She would roll them out by hand and cook them on top of the bottom of that tin top. And she would make potatoes and eggs. She used to cook potatoes in a big frying pan and she would crack a half dozen eggs. That’s how we ate eggs and potatoes. Fernando Chavez Interview by Margo McBane and Peggy Chavez, Feb. 6, 2008, Cupertino, CA.

-

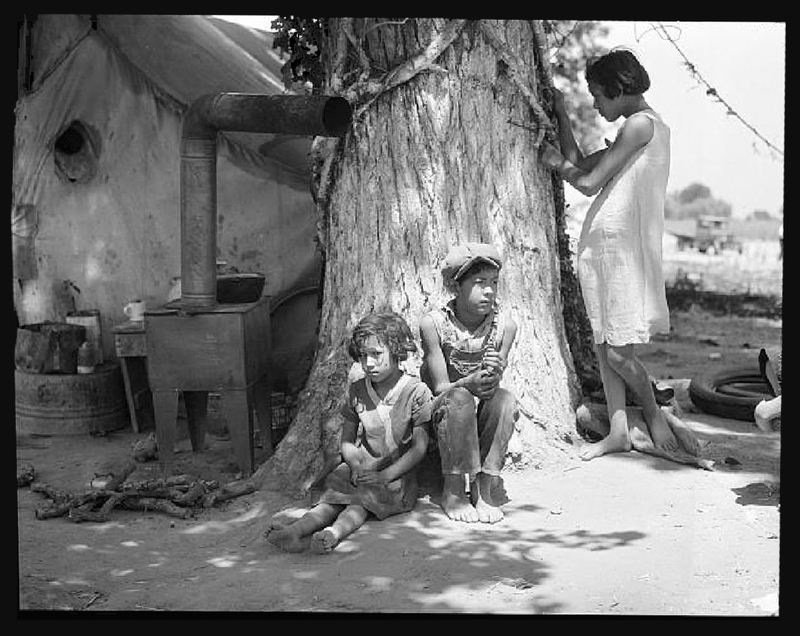

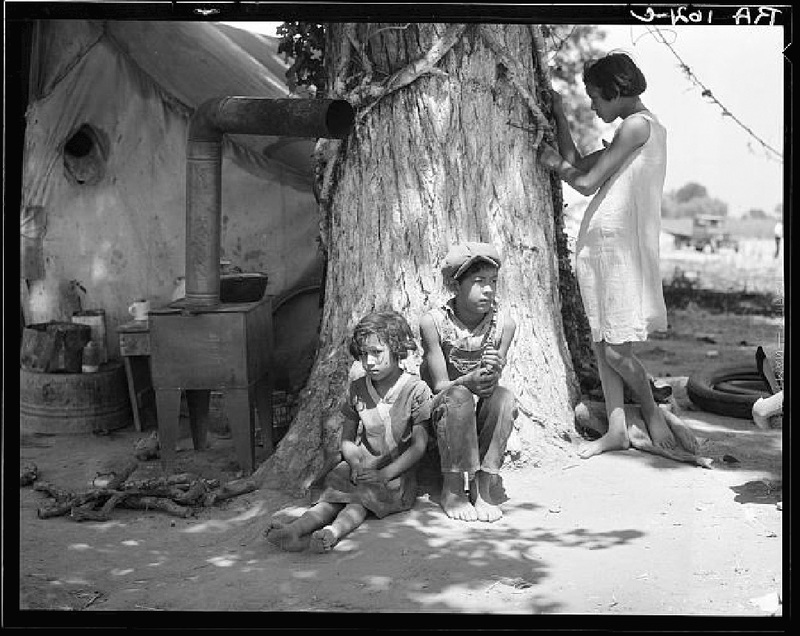

Migrant HousingMost Mexican immigrants arriving in the 1920s and 1930s could not afford to rent or buy permanent housing in Santa Clara County’s Mexican colonias. Early Mexican rail crews in Santa Clara County were housed in tents and work camps, bunkhouses, or in rooms near railyards. As adjacent communities and industries grew, boxcar housing in the railyards became the nucleus of the first Mexican worker neighborhoods. When they turned to migrant farm work, many Mexicans would camp on growers’ land. By the late 1920s and 1930s, migrant families acquired used cars and brought their own tents, mattresses, and cooking equipment on the road. Migrating in a car with a family of 12 or more was a challenge! During fruit season, workers found that most growers offered no housing or sanitary facilities, so they camped under bridges or in tents in the open fields or built temporary shelters with fruit boxes. Innovative families used wooden crates to create tables, chairs, cabinets, or bed platforms. Not until WWII did ethnic Mexicans come to settle more permanently in the segregated colonias of San José or Santa Clara County, called by Anglos “Mexicantown” or “Jimtown” in reference to Jim Crow laws of the South.

-

Ventura County 1941 Great Citrus Strike Refugees QuotesI lived in Santa Paula until I was 18. Then in February of 1943, I was drafted into the Army. My family was still living in Santa Paula. In [1941] the [Limoneira Company citrus] strike was lost, and my dad did not want to go back to picking lemons. They moved to San José… We knew San José best because we used to come and pick prunes [and apricots] here every year. The ranchers in San José would go and pick you up [in Santa Paula] because you couldn’t pack 13 kids and mom and dad in a car to come from Santa Paula…to San José with all your bedding and dishes and all the stuff you need because you were camping. The ranchers wanted to guarantee that they had enough workers to help pick their crops, so they would bring two extra families, three families, five families, six families. Whatever they needed. And then, after the apricots, then they would take you back. [In Santa Paula] we used to live in the Limoneira [Company] housing… In July, that is apricot season [in San Jose],.... In August, we used to pick prunes and then… we used to go back [to Santa Paula] and pick walnuts [and lemons]. So we knew there was a lot of work [in San José], you know, ranch work… irrigating, pruning, picking the crops and all that kind of stuff. [After WWII] [in San José] they worked year-round… -- cherries, pears… And then in the winter time you’d spray trees and prune the trees. There was always work. In San José, they had a lot of farm labor offices. All you had to do was call them up. The ranchers would call the farm labor office, and you would tell them, “I need three men, four men, to irrigate or prune or whatever, to pick or whatever”. Workers just call there and say, “I am looking for work.” And you didn’t have to go there. You could call up, and they would send you. That’s what my mother did. They knew her already. She’d call and say, “I have two men that want…work”. Then she’d tell my father and my brothers, where they needed help. And they’d just go there, and they had a job. [After WWII] I decided that I wanted to learn a trade, and, and the government was paying for it [through the GI Bill]. They would pay for you to go to school and learn something. That was part of the benefits you would get in the Army. And so I decided that I couldn’t go to college for four years because I already had two kids, and I worked to support them. I wanted something…that was better than working in ranches, and so, I picked barbering. And that’s what I have done for since 1950, 57 years. Fernando Chavez Interview by Dr. Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Peggy Wallace, Feb. 6, 2008, Cupertino, CA.

-

Ventura County 1941 Great Citrus Strike RefugeesOne group of Mexican migrants that came to Santa Clara County were from the citrus region of Ventura County, or the Southern Santa Clara Valley. (We use the term Santa Clara County here instead of Santa Clara Valley so as to clarify which region we are referring to.) In Ventura County citrus workers harvested the lemon crop during the winter months and were then available for other crops during the more traditional summer harvest season. Historian Margo McBane found that growers from the north sent trucks down to Ventura County (around the Santa Paula region) to pick up citrus worker families to live and work in Santa Clara County for the summer fruit harvest. After the Great Citrus Strike of 1941 in Ventura County, many of these workers, who had been evicted from company housing during the strike, as well as family and friends from the Santa Paula region, chose to come to work permanently in Santa Clara County.

-

Migration Routes Leading to Santa Clara County Quotes"My father was born in Sialo, Guanajuato and my mother was born in Big Springs, Texas. And my dad came across the border when he was two or three years old… Both my grandparents, my maternal and my paternal grandfather came from the same town, Iropato, Guanajuato. They came as farm workers. They worked on ranches in Mexico in Iropato, when they came [to the U.S.] they were farm workers. My father, and my mother’s father, my grandfather, worked on the railroad, the Union Pacific Railroad. And for that reason, I… have over 2,000 relatives in 46 states, the majority is in California, Texas, because of the railroad. They came prior to the Revolution, around 1910. That’s the reason my mother was born in Midland, Texas, because of the railroad. Midland is like the hub of the Union Pacific. What happened was when my grandfather’s family, mostly males, came up from Guanajuato, they came up to Texas, and that’s where they found the railroad. And so some of his brothers went to Illinois, some stayed in Big Springs, and the others, my grandfather and one brother came to California, and they landed in Wasco. They came for work. There was no family, they were the first of family there. That’s what drew everybody, you know, it was getting out of the fields, and doing something different, making money. My grandmother wasn’t happy, because when you’re working with the railroad you gotta move, and so my grandmother was always losing clothes, because she would wash and hang clothes out, and the train would leave! (laughs) They lived on the train. That was like luxury, if you could live on it. From Wasco, my mom had come to San José before, because her oldest sister, my Tia first came up to San José. She invited my mother to come to work in the canneries. My mom did, she came to work one summer, I think she was a senior in high school. And after school was over she moved back to San José. But in the ‘40s she went back home and met my dad in Delano at the dance. I don’t know their specific ages, but they were in their early 20s, and they got married at Sacred Heart church in San José in 1940, ‘cause I was born in ‘42." Richard Vasquez interviewed by Dr. Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Margarita Garcia Villa, Dec. 21, 2017, Watsonville, California "I was born in El Paso, Texas, June 30, 1936. So was my sister. [My parents] were from Mexico. They got married in 1930. They stayed in El Paso six years. My dad and grandfather worked on a dairy. Then we came from El Paso to LA in 1936, I was two months old. We had a lot of family living in LA, all our aunts. My dad's family was a family of 10. My aunts came in the 1930s, they were going to school in Downey because my aunt lived in Lakewood and the other aunt lived in Norwalk. They had a strawberry farm. I think they got married very young. Yeah. My aunt Tilly got married when she was about 14. Yeah. And then she got married. Neither aunt worked, only their husbands. I think we came to Santa Clara Valley in 1947. We ended up in Hollister and we didn't go back to LA again. I know when we came from L.A., there was an uncle of ours that said, with your kids, you could make a lot of money picking prunes. Oh, I didn't even know what prunes were. And ah we did for a little while, about 2 years. In Hollister we were cutting apricots because it was in June and then we came to Gilroy. And we were cutting grapes. But my dad had never picked. He worked in a dairy. So we ended up going back to the dairy. My dad got a job there and it was a milk vendor from Gilroy with Mr. Benny Gilroy." Julia Barrientos Interview by Dr. Margo McBane and Suzanne Guerra, April 23, 2012 at her home in San José, California "The camp was...Giffens Camp, and that was 1942…. In them days…every three months or every month...you could collect stamps, and that was the only way you could buy shoes for the family…because of the war. [We lived in a shed]. It was like 9x10 or 12. Well my dad used to put two of them together. And whenever we went to a camp, they could do that, put two cabins together. He'd get an extra one, you know, for the boys… We were all eight: five sisters, and three boys, and then my parents… My older brother used to make us kites. During the...the summer times, we'd spend it at the camp. All we did was just go swimming, they had little canals, irrigation ditches. And that's where we used to go jump in 'em and fool around. [This was in] Firebough, mostly cotton. Well that was when I was five years old. Then we lived in another camp, Briton Camp. that was in Firebough too. Nobody would stay home. My dad wanted everybody. “Let's go! Everybody is going.” [I would] make little bunches in the middle of the row. I would go in front of my mother or my dad and I would, you know, pick up the little bunches…[of cotton balls]... When it gets time for the cotton to start opening, the cotton falls to the sides. And that's when you pick… We used to go pick and cut those things…“Cabola.” Like the ball, we call it, “bola.” They always said, “Vamos a pescar la bola.” Let's go pick the bolas, the cotton balls. When you're picking cotton…when the thing opens up, the cabola opens, the ball opens up like that, they call that a “cabola.” It's all dry. And it has real sharp points on it. And when you go like that to get the cotton, you are hitting that with your fingers. A lot of people [wore gloves], but we couldn't afford em. A lot of people picked cotton, my sisters did. My father used to buy [my sisters gloves] so they wouldn't mess up their fingers. But they didn't care about us. When I was seventeen I still picked cotton. That's why I remember, that it messes up all your fingers. In that same camp, the Briton Camp. That was the only Christmas present I remember. [The camp owners] used to come around with a big truck and any kid that was outside, they would give you a little gift or something. And I got a little bus. It was a tiny bus. At that time they had a grader, that was leveling off the ground. So that when it rained, everything used to get all muddy and everything. So, they were gonna fix it. And I was playing with the truck out in the dirt. Then when I saw the grader coming, I got scared. So I took off running – that was in front of our cabin – and then when I went inside, I realized I forgot I left my bus outside. And when I was going to get the bus, that grader mashed it all up. That was the first toy I ever had. I said, “oh boy.” Workin' in the fields you can't make a life… The only way you could live, if is you had a big family. [The camp manager would ask], “How many are gonna pick?” And nobody could say no. They wanted most of the family to be pickers. They don't anybody staying home or anything. My aunt used to [stay home], like my uncle told them, “No, she can't pick, she can't work”, because she had..one or two little kids." Leandro Villareal Interview by Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Joseph Rivera, Aug. 28, 2008, at his home in San José, California

-

Migrant Routes Leading to Santa Clara CountyBefore WWII, Mexican immigrants joined the agricultural migrant routes that eventually led to the fields and orchards in what is now Santa Clara County. Due to the nature of their low-paid seasonal jobs, most ethnic Mexican migrants were unable to join permanent colonia settlements throughout the county. On the road, they might stay a week or a month working a crop in one location until the harvest ended and then moving onto the next. One route began in the lower part of California around San Diego or Imperial Valley, starting in February with row crops such as cantaloupe, tomatoes, or garlic. From there, migrants headed up to the Los Angeles area (primarily in the citrus orchards); then over the Tehachapi Mountains to the San Joaquin Valley working in row crops; then up through Bakersfield, Visalia, Fresno, Modesto and over Pacheco Pass to Hollister and Gilroy; then north to Santa Clara County; and finally back south again. A second route extended north from the Los Angeles citrus area up the Central Coast through Santa Barbara, Santa Maria and Nipomo, and the Salinas Valley working row crops. The route continued to Santa Clara County in June for orchard or row crops, then over to the Fresno area in August for grapes or other row crops, and then returning south to the Los Angeles area. Flood conditions in the Rio Grande Valley pushed a new group of Mexicans, particularly from Del Rio, Texas, onto the migrant path to Santa Clara County after WWII. These workers and their families joined California’s unskilled, low paid, seasonal migrant labor force, though many were eventually able to obtain cannery work and settle into permanent housing in Santa Clara County’s Mexican colonias.

-

Mexican Revolution Refugees QuotesThey had the Mexican Revolution, con (with) Francisco Villa, and all the trains, and the buggies. All the people [were leaving]. So my mother came in a buggy, and my dad just got with other people and they drove on horses to Texas. My mama was from San Luis Potosi and my dad was from Allende or Morelos, in the Chihuahua state. My mother came through…Piedras Negras! My dad was only nine, my mom was about five years old. They were children when they got here. My mama didn’t come with the rest of her family. She stayed with her godmother in San Luis City. And so later on one of her brothers went and got her from there, [and brought her to Poth, Texas]. So my mother was in Poth, in Poth City, and my dad he was in…Fall City. My mother was fourteen and my dad was twenty. My dad was working in the railroad in Fall City. They met in a ranch dance. Beatrice Sanchez interview by Dr. Margo McBane and Joseph Rivera, Sept. 9, 2006, San José, CA. My parents were born in Mexico. My father was born in 1900, and my mother was born in 1903. That was during the revolution of… Pancho Villa, because my father never liked him. He never wanted to hear his name...because he did a lot of damage to the people. Like he was in charge, he was a king… If he told a man, “I want your wife.” He could take her. And that’s what my grandfather didn't like. So they…and a lot of people, all came to L.A [from Durango] in 1906, I remember my father telling me. [They came to] San Bernadino mostly. There were all ranches, just ranches in Southern California and Duarte… So then they... all decided to spread out, all the families that came. Some of them stayed in Los Angeles, San Bernadino… My father and his father, and his mother and all, they decided to come to the crops, you know, grapes, and prunes, and all that around here. But [my mother] came with her family, and [my father] came with his family. My mother had...three sisters and two brothers… My uncle told us that he was nine-years-old, when their mother and father had an accident and they were both killed… Different people took [the kids] in. So one sister came to live in Lemoore and...the other one stayed in San Bernardino. My mother was already a teenager, she was the oldest...like fifteen and she married my father, he was about three years older.” Leandro Villareal Interview by Dr. Margo McBane, Ph.D. and Joseph Rivera, 8/28/2008, his home in San José, CA.

-

Mexican Revolution RefugeesWWI created a farm labor shortage in California as European immigration became restricted and Anglo American men were recruited into the military. During WWI the market for American crops expanded to meet Europe’s needs. After the war’s end in 1919, the 1924 Immigration Act ended all Asian immigration to the U.S. and created an even greater farm labor shortage in California, where many Japanese laborers were employed. Many Mexicans, pushed out of Mexico due to the ravages of the Mexican Revolution from 1910-1920, were now pulled into the U.S. to work in Southwest agribusiness. A wave of up to one million refugees sought employment throughout California while fleeing Mexico’s political instability, social turmoil, and poverty. By the 1920s, the California agricultural labor force became “Latinized,” with 82% of the jobs filled by ethnic Mexicans. Mexican immigrants soon filled the labor gap, traveling—and working along the way—by rail and later car. Most Mexican Revolution refugees traveled to the U.S. by train through El Paso. There was no rigid border between the U.S. and Mexico until the Labor Appropriation Act of 1924. Refugees joined Mexican traqueros or track workers, who had been working on U.S. railroads since the end of the 19th century. Not only did the Mexican Revolution refugees work on the railroads, but they also sought seasonal jobs in agriculture, working their way north to Chicago and west to New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The Mexican American path of agricultural migration throughout the U.S. had begun. According to historian Stephen Pitti, approximately 82% of all the ethnic Mexicans laboring in Santa Clara County in the 1920s and 1930s worked in unskilled and seasonal agricultural work.