Topic One Exhibit

Pre-Colonial Native Americans And Spanish Encounters

- Title

- Pre-Colonial Native Americans And Spanish Encounters

- Description

-

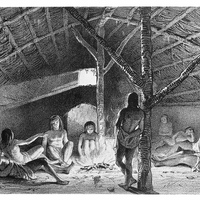

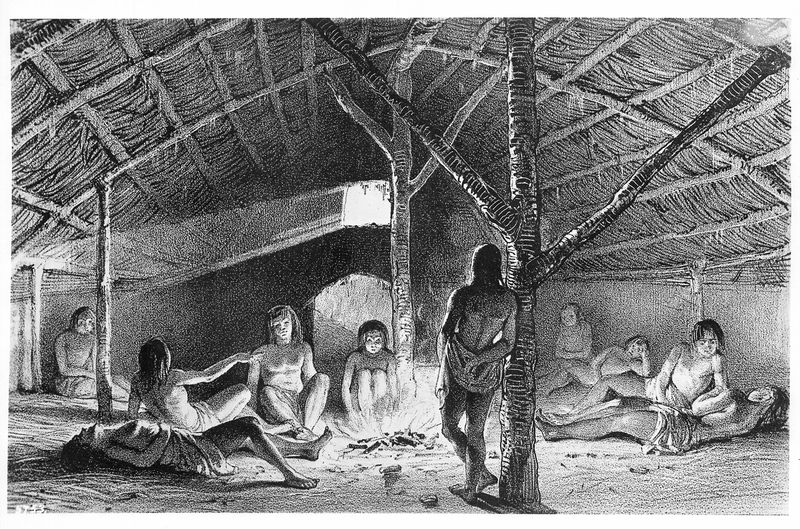

The original occupants of the Santa Clara County were the Ohlone tribelet of the Tamyen Coastanoan-speaking tribe. They thrived within a spiritual life grounded in animism and a lifestyle that balanced population to resources. Acorns were a staple of their diet. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber estimated that more than 75 percent of native Californians ate them on a daily basis. Tule bulrushes provided medicine, food, and fiber for housing, boats, clothing, and baskets.

At the time of Spanish settlement in the 1770s, the native California population was estimated to be approximately 300,000, or 13% of the native population of North America. - Additional Online Information

- The First Peoples of California | Library of Congress

- Native Americans: Pre-Columbian California to 18th Century — Calisphere

- Early California Exploration and Settlement — Calisphere

- Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (American Indians)

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 001

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Colonial Spanish Exploration, 1542-1768

- Title

- Colonial Spanish Exploration, 1542-1768

- Description

- With the arrival of Hernán Cortéz in Baja California, Spaniards explored the California Coast in the 1500s. In 1542, explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo ventured up to Santa Barbara looking for the mythical Strait of Anian, a supposed waterway linking the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. This imaginary shortcut would have allowed Spanish galleons easy access from the Port of Manilla in the Philippines to their trading partners in China.

- Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811383259/52599efcb0?share=copy

- https://vimeo.com/811383103/4fa47c5aaa

- Additional Online Information

- Early Exploration of California (Part 1 of 2)

- 1768-1820s: Exploration and Colonial California — Calisphere

- A History of American Indians in California: Pre-1769

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 002

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Spanish Settlement

- Title

- Spanish Settlement

- Description

-

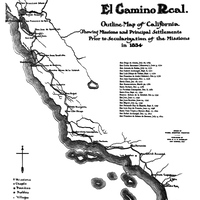

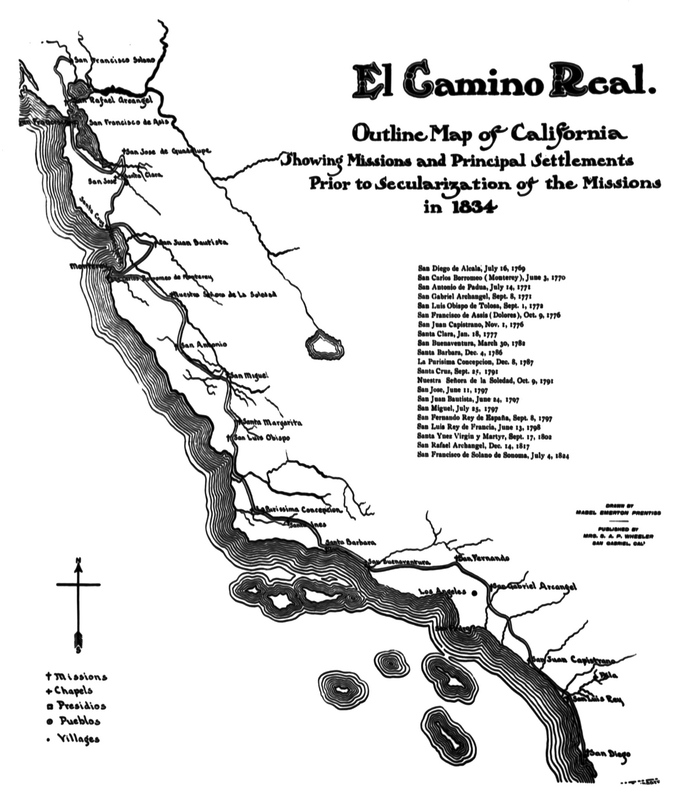

At the end of the Seven Years War (1756-1763), Spain established permanent colonies in Alta California (now known as California), which Cabrillo had claimed in 1542. Based on the Recopilación de las leyes de los reynos de las Indias (1680), the Law of the Indies, Spain aimed to transform native Californians into Catholics and productive Spanish citizens. The Spanish colonial system was based on three institutions–missions, pueblos, and presidios–established along the coast to protect and supply food for the Manila galleons, trading ships that transported goods from the Philippine colony back to Spain. The Alta California settlements were restricted to trading solely with the Spanish Galleons.

The Spanish built four presidios in Alta California–San Diego, Monterey, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara–to protect the missions and pueblos and control the enslaved Native American laborers. Three pueblos–San José de Guadalupe, Los Angeles, and Villa Branciforte–were established as civilian communities, occupied by retiring soldiers from the presidios, soldiers’ families, and settlers. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811383322/ee7b849dd1

- https://vimeo.com/811383418/8499406996

- Additional Online Information

- Spanish California | Library of Congress

- The Missions | Library of Congress

- Early California Exploration and Settlement — Calisphere

- Hispanic Americans: Spanish Colonization and Californios, 1769-1800s — Calisphere

- California Missions — Calisphere

- Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (American Indians)

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 003

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Spanish Settlements, 1769-1820, continued

- Title

- Spanish Settlements, 1769-1820, continued

- Description

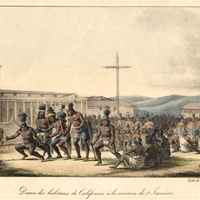

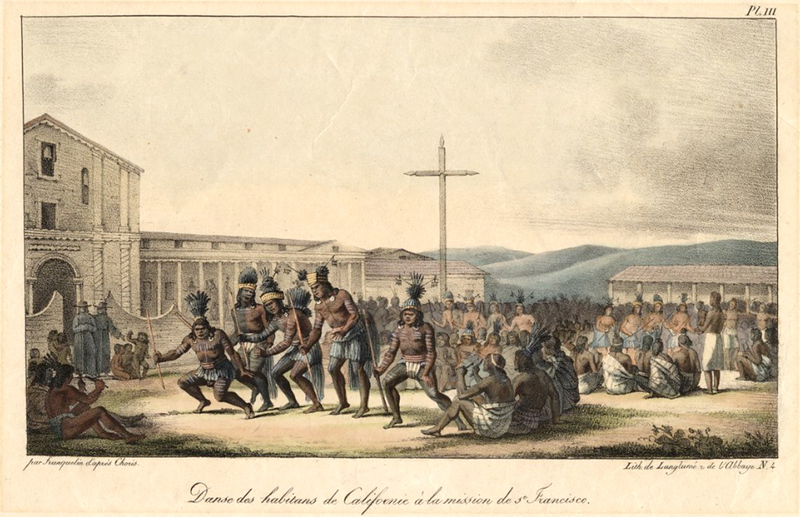

- Two out of the 21 missions were established in Santa Clara Valley: Mission Santa Clara de Asís (1777) and Mission San José (1797). Labor on these missions was performed by Natives from missions in Baja California brought to help acculturate local tribes, as well as native Californians from nine language groups. The majority came from the Tamyen Costanoan-speaking tribe of the South Bay and the Yokuts of the San Joaquin Valley. Before European contact, the Yokuts consisted of up to 60 tribes speaking several related languages. Spanish missionaries forced Natives to convert to Catholicism and work in the extensive mission fields, orchards, and workshops. To enforce church rules and prevent escape, two soldiers from a nearby presidio were placed at each mission, aided by Native converts (neophytes).

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 004

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, 1777-1848

- Title

- El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, 1777-1848

- Description

-

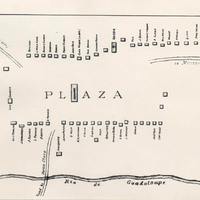

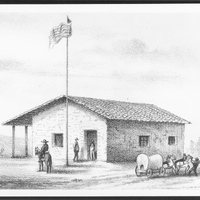

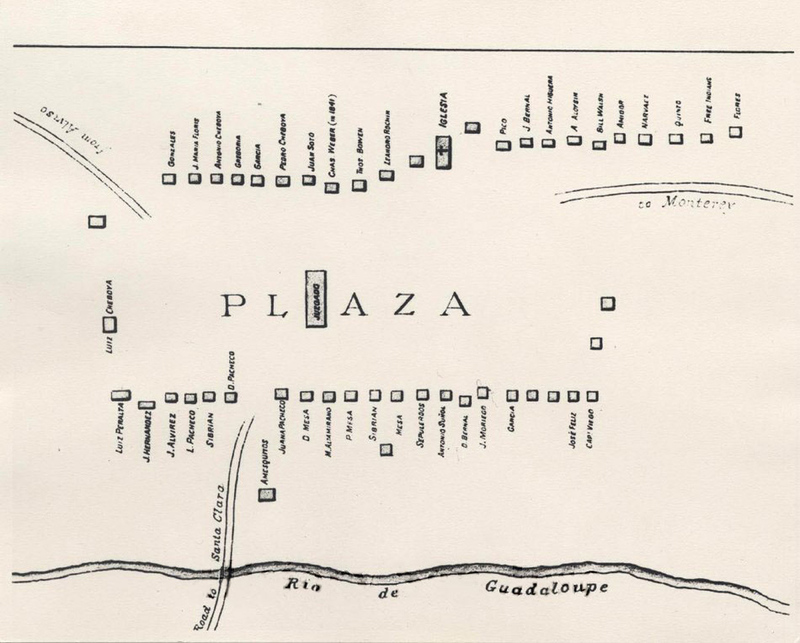

In 1776, the Spanish king sent Captain Juan Bautista de Anza on an expedition to lead settlers from New Spain to California. Stopping first in Monterey, De Anza continued north to establish the Presidio of San Francisco and Mission San Francisco de Asís. In 1777, Governor Felipe de Neve, the Presidio’s commandant, ordered 68 residents to establish Alta California’s first pueblo, Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, named after the Catholic Saint Joseph and the Guadalupe River, where it was originally located. In 1791 due to flooding the pueblo was moved to a plateau (now Market Street Plaza).

Each pueblo attracted pobladores (settlers) with small land grants of four square leagues (a league being about 4,228 acres) for housing, crop farming, and cattle grazing. Soldiers or settlers could also receive small lots or solares just outside the pueblo. The nearby presidio commander controlled the state-owned land used for livestock or farming. Each pueblo was governed by an alcalde (a combination of a judge and a mayor) assisted by the ayuntamiento (city council), whose offices were located in the juzgado (jail, town hall and courthouse). - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811441524/7d36224748

- https://vimeo.com/811441775/d48ed757da

- https://vimeo.com/811441845/09fa2c7102

- Additional Online Information

- Founding Families - Los Californianos

- A Year in the Life of a Spanish Colonial Pueblo: San José de Guadalupe in 1809 — Google Arts & Culture

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 005

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, 1777-1848, continued

- Title

- El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, 1777-1848, continued

- Description

- The Pueblo’s pobladores, most of whom came with Captain Juan Bautista de Anza’s expedition of 1775-1776, lived under a strict hierarchy or Sistema de Casta (caste system). One person of pure Spanish blood (pureza de sangre) occupied the top rung, with below them the mestizo (mixed Spanish and Indian), the mulatto (mixed African and Indian), then the indio (Native), and lastly the Africans. Initially Pueblo San José included five mulattos and twelve mestizos (one servant, nine soldiers, five pobladores, one male herdsman, and their wives and children).

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 006

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Mexican Rancho Period, 1821-1848

- Title

- Mexican Rancho Period, 1821-1848

- Description

-

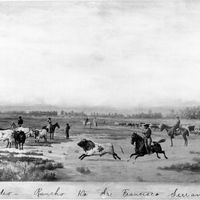

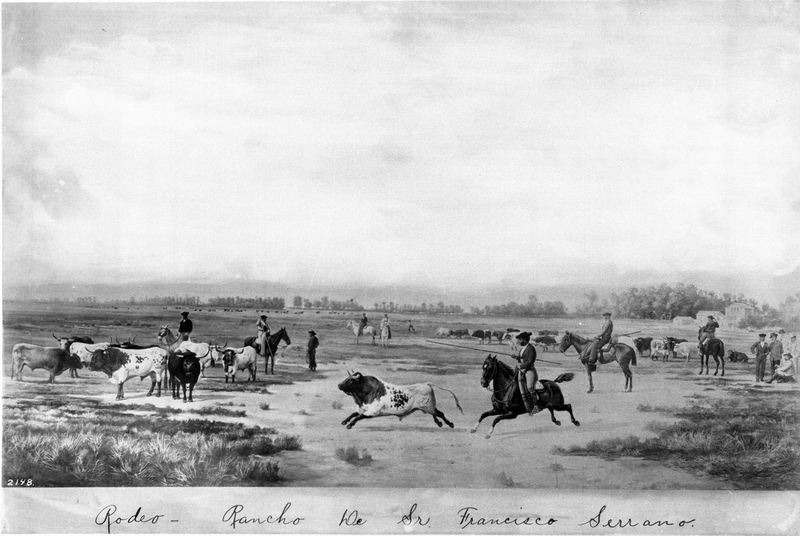

In the early 1800s, Mexicans revolted against Spanish colonial rule and gained independence in 1821. During the Mexican Period of 1821-1848, the Catholic Church lost most of its land holdings in Alta California except for property surrounding church buildings. After secularization in 1833, a wholesale transfer of land grants to the Californios (la gente de razon–the Christianized residents) took place. Ranchos employed between twenty and several hundred laborers. The original plan to grant the land to the converted Indians was never implemented. A social system of seigneurialism took hold in which Californio rancheros, the land owners, and their mestizo and Indio laborers lived in a world of mutual obligation. In this paternal system, rancheros provided housing, food, and clothing to workers in exchange for their labor.

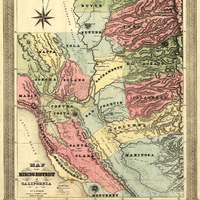

During the combined Spanish and Mexican rancho periods, 500 land grants were issued, with the majority (450) carved from mission land holdings after secularization. Mexico’s 1824 Law of Colonization specified that the maximum land grant could be 48,400 acres, with the average being 22,000 acres. No longer restricted to trading only with Spanish galleons, Mexicans began engaging in “the hide and tallow trade” internationally. Mexican hides, known as “California dollars,” were used to make shoes, leather belts, and other items, helping propel the United States’ early industrial revolution of the 1820s and 1830s. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811441701/cd2acca19b

- https://vimeo.com/811441775/d48ed757da

- https://vimeo.com/811441940/ffee9b6d70

- Additional Online Information

- Mexican California | Library of Congress

- Land Grants in Alta California

- Battle of Santa Clara - Clio

- Californio Society — Calisphere

- Witness to Empire: The Life of Antonio Maria Sunol

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 007

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Americans During the Mexican Period, 1810s-1840s

- Title

- Americans During the Mexican Period, 1810s-1840s

- Description

-

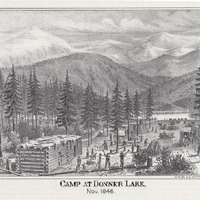

Anglo Americans first began settling in Alta California during the Mexican Period. in the 1830s-1840s, pioneers such as Johann Sutter (John Sutter) settled in the San Joaquín Valley, taking advantage of unprotected Mexican settlements that had little-to-no government oversight. Americans who wanted to live in Mexican California did have to follow Mexican law and convert to Catholicism if they wanted to become Mexican citizens. Many did, marrying into Mexican families, acquiring land grants, becoming rancheros, and joining the lucrative Mexican hide and tallow trade. Some of these settlers included English immigrant William Edward Petty Hartnell and Scottish immigrant John Cameron, who jumped ship in 1814 and was baptized and renamed Juan Bautista Gilroy at Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Rio Carmelo. He then married into the Ortega family.

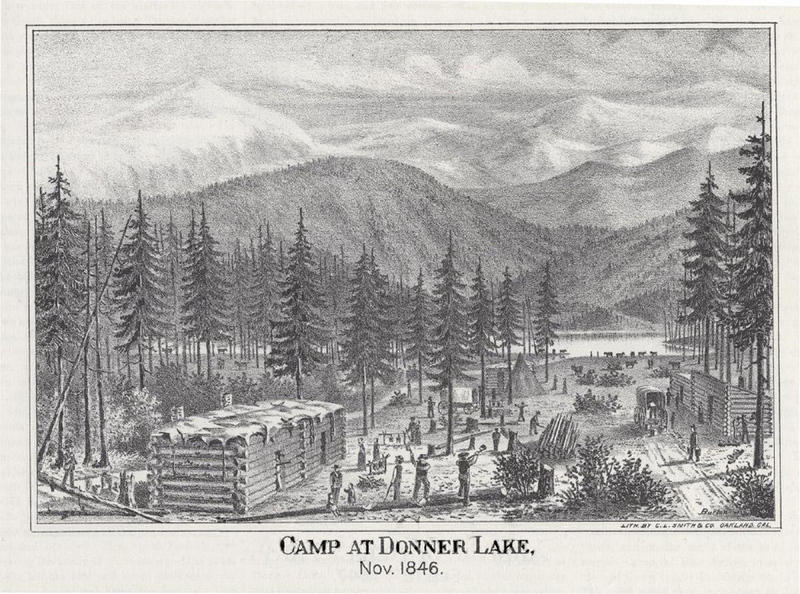

Some of the more famous American settlers of El Pueblo de San José were members of the Donner Party, including Eliza Poor Donner, Mary Donner, William McCutchen, and the Reed Family (who purchased a 500-acre ranch between First Street and Coyote Creek). As Irish Catholics, they immigrated to Catholic Mexican Alta California hoping to be spared the anti-Catholic prejudice they had experienced as residents of the United States. The City of San José named several streets after the Donner Party: Reed, Margaret, Virginia, Martha, Carrie, Patterson, Lewis, and Keyes. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811441967/b6b9786df1

- Additional Online Information

- Watch The Donner Party | American Experience | Official Site | PBS

- Endless Winter: A Fresh Look at the Donner Party Saga | KQED

- William Hartnell: The Hero and His Colleges, by Sean F. Roney

- The Story of a California Pioneer - The New York Times

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 008

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

The Mexican American War (1846-1848)

- Title

- The Mexican American War (1846-1848)

- Description

-

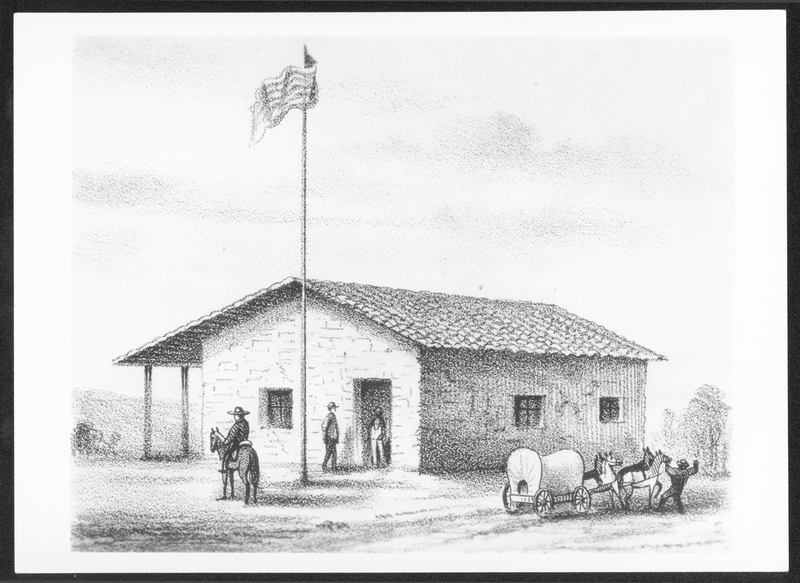

Many Anglo Americans who settled in Mexican California chose not to become Mexican citizens, siding with the movement to incorporate California into the United States under forces led by John C. Fremont. Canadian immigrant Thomas Fallon joined Fremont’s third expedition to California and settled in Villa Branciforte (Santa Cruz). He then declared himself “captain” and crossed the Santa Cruz Mountains with the purpose of taking Pueblo San José, rejoining Fremont’s forces and raising the American flag over the juzgado (the Mexican city hall and jail). He later became mayor of San José in 1859, during the American period.

The tensions that arose during the war served as an indicator of the future demise of the Mexican Californios under American rule. During the Mexican American War (1846-1848), the only battle fought in Northern California took place in Santa Clara County. “The Battle of Santa Clara” or “The Battle of the Mustard Stalks” took place in a mustard field near today's Triton Museum. American sailors, who came ashore to buy supplies from the Mexicans, were taken hostage. The battle lasted only two hours and resulted in the death of four Mexican soldiers. The battle, ironically, impacted James Reed of the ill-fated Donner party. Reed was in the area trying to recruit a rescue team for his trapped comrades in the Sierras but was unsuccessful during wartime. In 1846, the San José-based Berryessa family fell victim to Anglo-American hostilities. José de los Reyes Beryessa and his twin sons were murdered by the California Battalion, who stole their horses. The Mexican American War ended in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811460873/fb42898de0?share=copy

- Additional Online Information

- The United States and California| Library of Congress

- Battle of Santa Clara - Clio

- Mexican-American War: Causes & Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo - HISTORY

- Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (Mexican Americans)

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 009

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

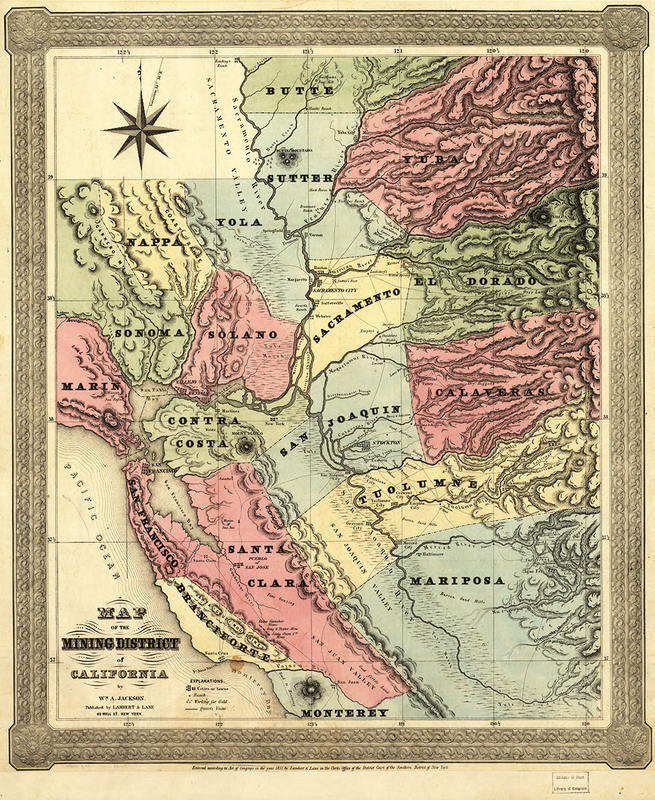

Mexicans and The Gold Rush, 1848-1855

- Title

- Mexicans and The Gold Rush, 1848-1855

- Description

- In 1848 gold was discovered in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and prospectors flooded in from around the world, including between 10,000-20,000 Hispanic miners from Mexico and Chile. The Californios who attempted mining were pushed out–some by violence and lynching. Others were forced to leave when selective taxes were imposed on them, such as the 1850 California Foreign Miners License Law ($20/month). This applied to all Mexican miners, even those who were citizens. Mexicans joined foreign miners in protesting the tax, but were subdued by white militias. Many of the immigrant Hispanic miners took refuge in San Jose. According to historian Stephen Pitti, between 1845-1860 the Spanish-surnamed population of San José increased by 150%.

- Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811383103/4fa47c5aaa

- https://vimeo.com/811383259/52599efcb0

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 010

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Mexicans and the Gold Rush, 1848-1855, continued

- Title

- Mexicans and the Gold Rush, 1848-1855, continued

- Description

-

Many Anglo and Mexican residents in and around Santa Clara Valley made their fortunes selling supplies to the gold miners. At the end of the Mexican American War, Thomas Fallon returned to San José and then to Santa Cruz, where he established a saddle business. At the beginning of the Gold Rush, Fallon took iron picks to the Sierras to sell to the miners. With his profits he bought a business/residence on the Santa Cruz Plaza and in 1849 married into a prominent Californio family that owned Rancho Soquel. Similarly, Don Antonio María Suñol, who owned a dry goods store in San José, supplied beef and dry goods to the miners. Other Californio rancheros, such as the Bernal brothers Juan Pablo and Agustin, joined Suñol and his family driving cattle to sell to hungry miners.

Businesses prospered as would-be miners passed through Santa Clara, Milpitas, Sunnyvale, Mountain View, and San José, needing supplies on their way to the goldfields. Often, miners waited out the winters in the warmer Santa Clara Valley. Discouraged miners also left the Sierras for good and settled in agricultural valleys like Santa Clara County in search of new livelihoods. This influx of settlers initiated a decline in Mexican culture and political influence, in contrast to Southern California, which retained its Mexican majority through the 1870s. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811383418/8499406996?share=copy

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 011

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Mexicans and the Gold Rush, 1848-1855, continued

- Title

- Mexicans and the Gold Rush, 1848-1855, continued

- Description

-

Many Anglo and Mexican residents in and around Santa Clara Valley made their fortunes selling supplies to the gold miners. At the end of the Mexican American War, Thomas Fallon returned to San José and then to Santa Cruz, where he established a saddle business. At the beginning of the Gold Rush, Fallon took iron picks to the Sierras to sell to the miners. With his profits he bought a business/residence on the Santa Cruz Plaza and in 1849 married into a prominent Californio family that owned Rancho Soquel. Similarly, Don Antonio María Suñol, who owned a dry goods store in San José, supplied beef and dry goods to the miners. Other Californio rancheros, such as the Bernal brothers Juan Pablo and Agustin, joined Suñol and his family driving cattle to sell to hungry miners.

Businesses prospered as would-be miners passed through Santa Clara, Milpitas, Sunnyvale, Mountain View, and San José, needing supplies on their way to the goldfields. Often, miners waited out the winters in the warmer Santa Clara Valley. Discouraged miners also left the Sierras for good and settled in agricultural valleys like Santa Clara County in search of new livelihoods. This influx of settlers initiated a decline in Mexican culture and political influence, in contrast to Southern California, which retained its Mexican majority through the 1870s. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811383418/8499406996?share=copy

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 011

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

The Early American Period: The Mexican Colonia and Anglo San José, 1848-1919

- Title

- The Early American Period: The Mexican Colonia and Anglo San José, 1848-1919

- Description

-

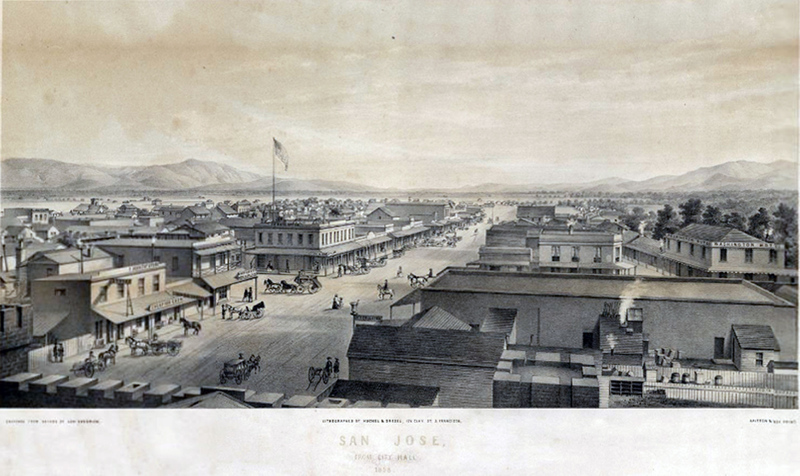

In 1848 after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican American War, California became part of the United States. Anglo Americans now controlled the levers of power, and Mexicans struggled to retain their political, economic, and social status. In 1850 California entered the U.S. as a free state, and San José (initially called St. Joseph by the Americans) was the first incorporated city, growing rapidly from approximately 900 in 1845 to approximately 3,400 in 1860. San José also served as California’s first state capital between 1851-1853. Americans moved the central commercial district of St. Joseph away from the Mexican pueblo (known as the colonia) located on Market Street between the Guadalupe River and Santa Clara Avenue to a new area, First Street between St. John and San Fernando streets.

St. Joseph became a segregated town as the Anglo ex-miners who settled in the area attempted to subjugate the original Mexican residents, preventing them from participating in American culture, economic opportunities, and politics. Out of the 48 delegates to the 1849 California Constitutional Convention in Monterey, at least eight were prominent Mexican Californio families from San José. Yet Mexican Californio political power in Santa Clara County had declined dramatically by the 1870s. As a result, displaced Mexican landowners began to settle in the downtown colonia, alongside the pueblo’s Mexican tradesmen, craftsmen, shopkeepers, professionals, and their families. Mexican residents, now restricted to living in the footprint of the old Pueblo, were marginalized in the new Anglo community. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811460752/d6366be72a

- https://vimeo.com/812203586/c439025dcd

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 012

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

- Media

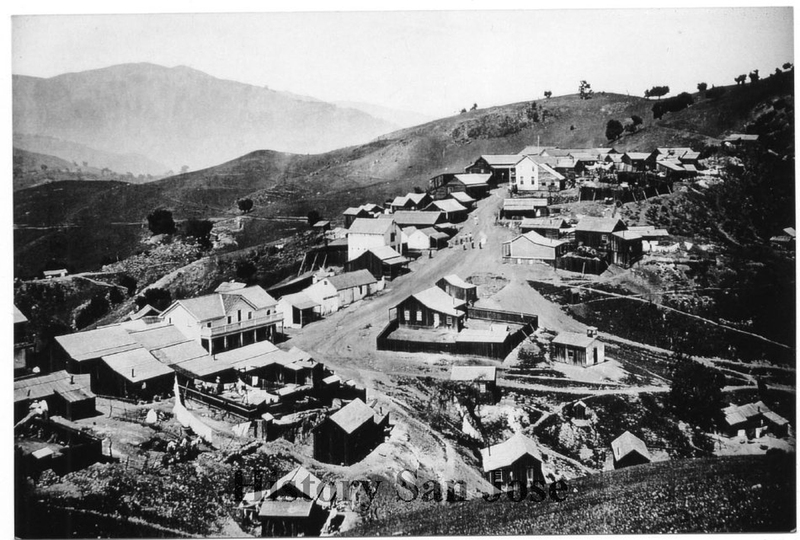

1858 San José

1858 San José

Mexican Loss of Land, 1850-1880

- Title

- Mexican Loss of Land, 1850-1880

- Description

-

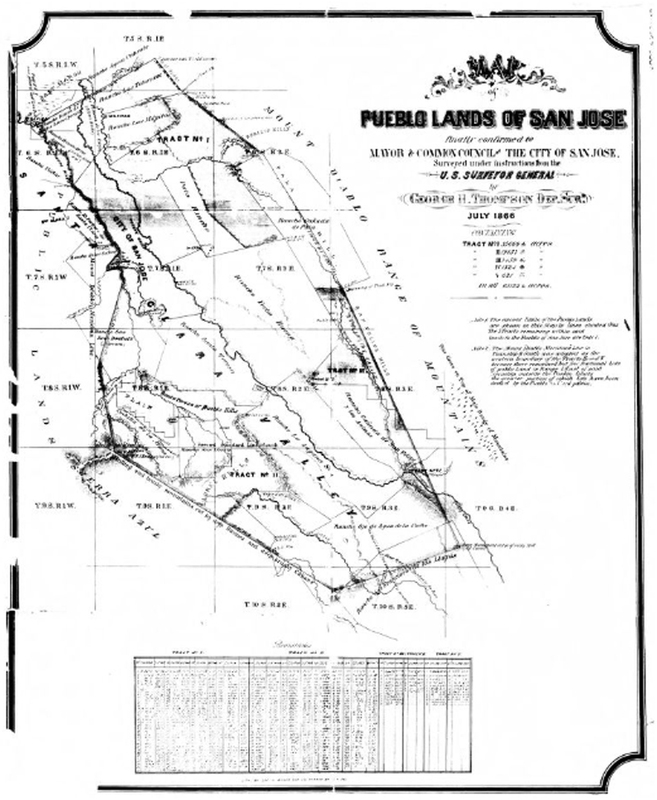

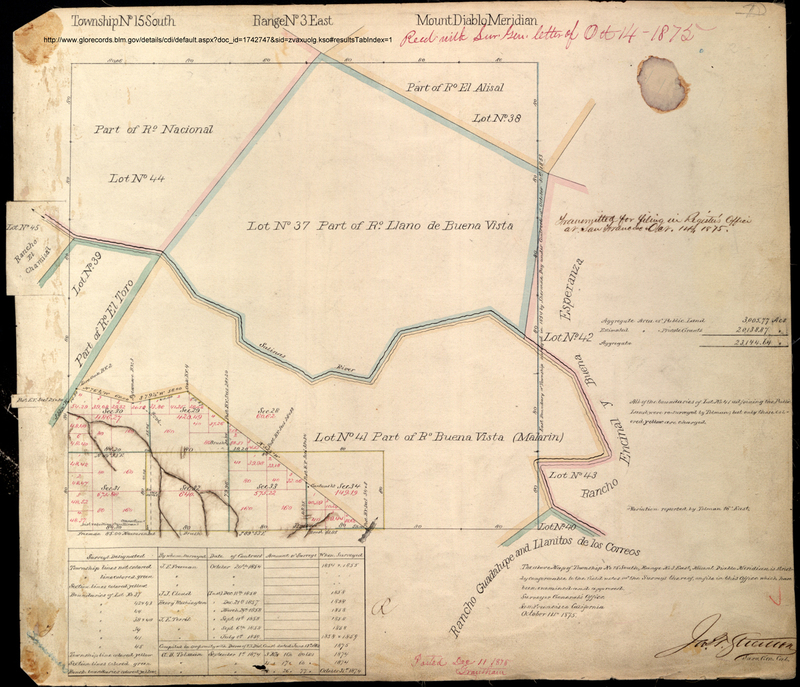

At the end of the Mexican American War in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted Mexican Californios full U.S. citizenship. At that time, only white males were granted U.S. citizenship, thereby implying Mexican Californios were considered “white.” The Treaty also promised Californios that “their property would be inviolably respected.” However, American political leaders held racist attitudes towards Native Americans and Mexicans, considering them lazy and unproductive in terms of their land use.

Race-based laws, enacted by the state legislature in the 1850s and 1860s, institutionalized discrimination and segregation against Mexicans, Blacks, Asians, and Native Americans. Significantly, the informal nature of land grants belonging to Mexicans, with vaguely drawn diseño maps, made it difficult to prove their claims, and many Mexican Californios lost their lands. Even if Mexican Californios won initially, the U.S. Congress created the Board of Land Commissioners (a result of the Land Act of 1851) in San Francisco. Mexicans gradually sold most of their land during the average 17 years it took to go through the legal process of proving their claims, and resulting funds went to English-speaking lawyers or to pay land taxes.

Mexicans also lost their land to Anglo American squatters. In some cases, such as with the Suñol and Berryessa families, Anglo squatters lynched the Mexican landowners and remained on the land, exercising their “squatters’ rights.” The Peralta family of San José and the East Bay lost all but 700 of their 49,000 acres. With the loss of land holdings during the late 1800s, Californio families worked wage labor jobs, such as in agriculture or in the Almaden mines. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811442262/af0c6facf9

- https://vimeo.com/811460819/4239257d1d

- https://vimeo.com/811442487/d4ed81f0ea

- https://vimeo.com/811441524/7d36224748?share=copy

- Additional Online Information

- Other Californians | Library of Congress

- Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (Mexican Americans)

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 013

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

- Media

1871 Pueblo San José

1871 Pueblo San José

Mexican Loss of Land, 1850-1880, continued

- Title

- Mexican Loss of Land, 1850-1880, continued

- Description

-

In Santa Clara County, the experience of Marie de Los Angeles Castro’s family is an example of the corrupt legal process during that time. Prominent as a founder of Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe and part of the De Anza Expedition in the 18th century, Joaquín Ysidro Castro served at the San Francisco Presidio. His family moved into Mission Santa Clara and was given one the few Spanish land grants: Rancho Buena Vista. During the Mexican period, Joaquín’s son José Mariana Castro acquired Rancho Las Animas and Rancho La Brea, near Gilroy, which was inherited by María Dolores del Carmen Castro and later María de Los Angeles Castro. In Castro’s words:

“Today I am old and poor. The young men who were my friends who made the papers for me to sign are all very rich. They have hundreds of acres of land and much money while I sit here like an old owl in the dark corner and tell the few who ask that these men have robbed me of all that was mine by their crooked talk and their crooked laws. They smile and tap their heads and say “dreaming.” And maybe it is so that I am dreaming. Maybe old age and sickness and sorrow have climbed into my eyes and brain just as ivy climbed into the broken window of my old Casa Adobe and shut out the light of reason. But this! If this is dreaming, tell me why these men once so poor are now so rich and I am now so poor? Hold my hands Señor, look into my old eyes and tell me, if you can, why it is that out of my vast inheritance I have nothing but poverty.” From Peter Ostroske Family Archive - Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 014

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Mexican Criminalization

- Title

- Mexican Criminalization

- Description

-

By the early 1860s, Californios faced deteriorating economic, social, and political status, suffering “a second conquest” by the Americans. As historian Stephen Pitti notes, Anglo Americans racialized their views of Californios seeing the entire Mexican population as oversexed, criminal degenerates. Mexicans became the victims of racial violence as self-appointed Anglo vigilantes shot or hung any Mexicans they considered criminals.

Mexican Californios were called “greasers," a term originating from the Mexicans engaged in the hide and tallow trade who, while processing beef fat, became covered with grease. In 1855 the California Greaser Act was passed, an anti-vagrancy law targeting all ethnic Mexicans. Further, the California Act of 1855 ended the State Constitutional requirement that laws be translated into both Spanish and English. These laws institutionalized racism in Santa Clara County, encouraging harsher punishments for non-white residents. Historian Stephen PItti points out that between 1850-1864 “all but one of the accused criminals hung in the county were ethnic Mexicans.” Mexicans could not sit on a county grand jury until the 20th century, and between statehood in 1850 to 1900 Mexicans could not become a sheriff or police officer.

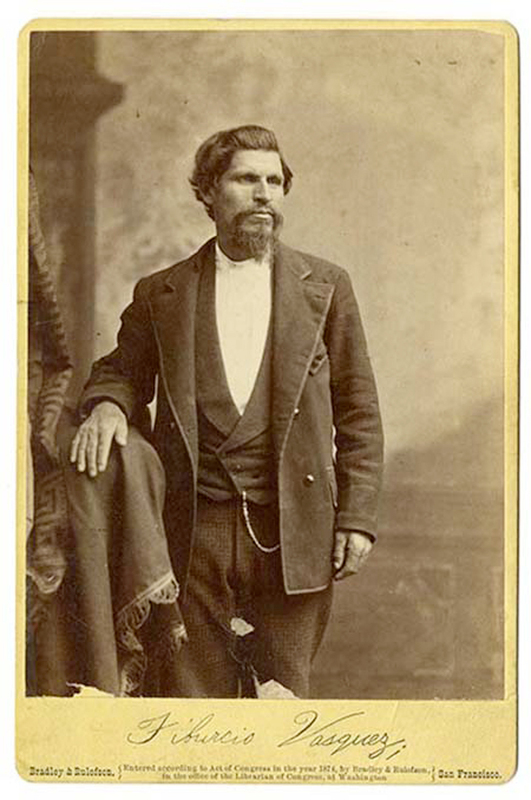

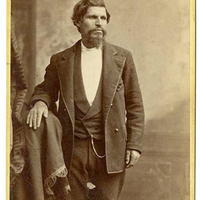

Without legal protection and with limited access to land or jobs, during the 1860s and 1870s a few Californios became bandits or highwaymen to avenge the harassment and racial discrimination Mexicans residents endured. Joaquín Murieta is the most famous of the “social bandits.” Tiburcio Vásquez, grandson of the first mayor of San José and an educated, bilingual member of an upper class Californio family, was another. Some Californios considered Vásquez a “Robin Hood,” fighting against Anglo atrocities and upholding Mexican civil rights. Anglo Americans considered him an outlaw. Accused of crimes committed from 1854 to 1874, he was tried and convicted for one murder and executed by hanging in 1875 in the jail yard behind Santa Clara County Court House across from St. James Park. While he admitted that he was an outlaw, Vásquez came to symbolize resistance due to legitimate grievances against Anglo American domination and Mexican lynchings that had become all too common. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811441940/ffee9b6d70?share=copy

- https://vimeo.com/811441845/09fa2c7102?share=copy

- https://vimeo.com/811441775/d48ed757da?share=copy

- https://vimeo.com/811441701/cd2acca19b?share=copy

- Additional Online Information

- The Lynching of Persons of Mexican Origin or Descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928

- From the Community | America’s History of Lynching Mexicans

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 015

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

- Media

Tiburcio Vasquez

Tiburcio Vasquez

Mexican Criminalization continued

- Title

- Mexican Criminalization continued

- Description

-

ANTI-VAGRANCY ACT (THE "GREASER" ACT)

CHAPTER CLXXV

AN ACT

To Punish Vagrants, Vagabonds, and Dangerous and Suspicious Persons

(Approved April 30, I856)

The People of the State of California, represented in Senate and Assembly, do enact as follows

Section 1. All persons except Digger Indians, who have no visible means of living, who in ten days do not seek employment, nor labor when employment is offered to them, all healthy beggars, who travel with written statements of their misfortunes, all persons who roam about from place to place without any lawful business, all lewd and dissolute persons who live in and about houses of Ill-Fame; all common prostitutes and common drunkards may be committed to jail and sentenced to hard labor for such time as the Court, before whom they are convicted, shall think proper, not exceeding ninety days.

Section 2. All persons who are commonly known as "Greasers" or the issue of Spanish and Indian blood, who may come within the explained that his aim was to return California to Mexican rule and avenge the loss of the rights of Mexican Americans. An outlaw to some, and a folkhero to others, much like the mythic Zorro, provisions of the first section of this Act, and who go armed and are not known to be peaceable and quiet persons, and who can give no good account of themselves, may be disarmed by any lawful officer, and punished otherwise as provided in the foregoing section.

Section 3. It shall be the duty of any Justice of the Peace, on knowledge or on written complaint from any creditable person of the State, to issue his warrant to apprehend such person or persons, and upon due conviction to send such person or persons to jail, as prescribed in section first of this Act; and on a second conviction for second the same offense any offenders may be sentenced to the County Jail for such additional time as the Court may deem proper, not exceeding one hundred and twenty days…” - Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 016

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Mexican Labor in the Almaden Mines

- Title

- Mexican Labor in the Almaden Mines

- Description

-

Facing ongoing social, political, and economic marginalization in Anglo American San José in the 1850s and 1860s, many Mexicans sought jobs in the thriving Almadén Mining Company, which became the second largest producer of mercury in the world. According to historian Stephen Pitti, The New Almadén Mine became the first industrial site in the West to employ Mexicans. Members of the Berryessa, Alviso, and Suñol families joined other Mexican and Chilean immigrants to work at the company. As Pitti notes, the low-paid Mexican mine workers formed the largest community of Spanish speakers anywhere in California.

Gaining the expertise of miners from northern Mexico was a boon to the company. Almadén became very successful and in turn provided job security, of a sort, for Mexican workers. Workers often had to compete at Almaden: wages were kept low by workers underbidding each other to continue employment. Working conditions were also extremely hard, and Mexicans were restricted to heavy manual labor, often working in teams of six to eight men in ten-hour shifts. Laborers climbed ladders, carrying heavy sacks of ore (some up to 300 pounds) on their backs “with a strap over their forehead.” The work continued day and night, six days a week. Work and living environments were segregated. Cornish or Irish worker families lived in “Englishtown” located down the hill from the mines, while Mexican miners’ families lived at the desolate top of the hill in “Spanishtown,” near the mine’s smokestacks that spewed mercury fumes. The toxic environment destroyed families’ attempts to raise poultry or vegetables; the company compounded the problem by dumping tailings from the mines next to and between the worker’s homes. Unable to produce their own food, Mexican miners grew more dependent on the mine owners for food, buying expensive groceries from the nearby company store. The closest water was located a mile away at the Hacienda, the offices of company management.

Pitti notes that these harsh working and living conditions drove the Mexican miners “to make new political demands and hone a sense of Latino identity for the first time in U.S. history.” - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/811460873/fb42898de0

- https://vimeo.com/811442085/e321eb3e5a?share=copy

- https://vimeo.com/811442033/a2ab5eadc9?share=copy

- Additional Online Information

- New Almaden - U.S. National Park Service

- New Almaden Quicksilver County Park Association

- “New Almaden and The Mexican” SJSU thesis (1977)

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 017

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley