Items

-

The Founding Members of the CSO San José Chapter, Excluding Cesar ChavezThe following are some of the founding members of the CSO San José Chapter: Herman Gallegos became the first president of the San José Chapter as well as president of the national CSO in 1960. Gallegos grew up in a poor coal-mining family who lived in a mud hut built by his father near the mines in Ludlow, Colorado, where he observed the infamous “Ludlow Massacre” of striking workers. After the massacre, the family moved to San Francisco. Gallegos first attended San Francisco State University, where two of his professors, Dr. John Beecher and Dr. Herbert Bisno, refused to sign a loyalty oath required under the Levering Act affirming that the signer was an American and not a Communist or risk being fired. When a state police officer came into the classroom and handed Dr. Beecher a letter requiring him to leave, Gallegos and two Jewish students walked out of class and went to the administration office demanding the professor be reinstated. Because the protesting students did not have a permit, the police broke up the protest, and Gallegos decided to transfer to the Social Work Program at San José State College. When he joined the CSO, he was attending college, living on the Eastside, and working as a gas station attendant. At that time he and Hernández were the only two members of the organization with a college education. In 1960 Gallegos became national CSO president, with César Chávez serving as executive director. Alicia Hernández, a public health nurse who worked with families on the Eastside, became a founding member after attending Fred Ross’ first talk at San José State College (with Herman Gallegos, Juan Marcoida, and Leonard Ramierez). She became the first temporary chair or interim president of the CSO San José chapter. A friend of Chávez’ wife Helen, Hernández arranged the first meeting between Ross and César Chávez, who was 25 years old. Hernández and Chávez walked door to door in the Eastside registering voters. Juan Marcoida, another student who heard Ross’s initial talk at San José State, was an engineer who worked by day and went to college at night. He became a founding member of the CSO San José Chapter while working at the General Electric Plant, where he’d been employed since its opening in 1947. A resident of Sal Sí Puedes in the Eastside, Marcoida served two terms as president of the CSO San José Chapter. He also hosted a radio program called CSO INFORME that aired for ten years on KLOK and KSJO radio stations, highlighting jobs, legal issues, police brutality, domestic abuse, immigration, deportation, scams, and voter registration assistance. He was named “1956 Man of the Year” in El Excentrico magazine. Rita Chávez Medina, the eldest of the Chávez siblings, had quit school at age 12 to help support the family after they lost their farm. She continued to work in the fields, transitioning into cannery work when she married and her family moved to San José. There she became active in local efforts to obtain a Catholic church to serve the Mexican community in the Eastside, enlisting the help of her brothers César and Richard, a union carpenter. She had already demonstrated her organizing skills in the church campaign when César asked her to work on the CSO voter registration drive, and he increasingly delegated local organizing tasks to her. Rita rose to become CSO San José Chapter President. Leonard Ramirez, who also heard Ross’ speech, and his wife Erma became founding members of the CSO San José Chapter, fighting for paved streets and street lighting as well as promoting voter registration. Ramirez led the CSO drive to abolish citizenship requirements to receive Social Security benefits for old age. The law was revised in 1960 taking out Social Securities citizenship requirement. Ramirez was born in Watts, California, in 1926. After high school, he joined the army during WWII. Through the help of the GI Bill, he graduated from San José State College in 1953, one of only five Mexican students attending the university.

-

The Formation of the San José Chapter of the CSOIn 1951 San José State College sociology professor and American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) member Claude Settles brought Fred Ross, Sr., to campus to give a lecture. Herman Gallegos, a student, and Leonard Ramirez and public health nurse Alicia Hernández, two community members, attended that lecture and encouraged Ross to organize a new CSO chapter in the barrio known as “Sal Sí Puedes“ (meaning “Get Out if You Can,” a name that can be traced back to a Mexican land grant) in the Mayfair district of East San José. Assigned to a project in Kansas City, Ross reached out to his contacts in Santa Clara to provide local assistance and support. One of these was Quaker philanthropist and AFSC member Josephine Duveneck of Los Altos Hills. Duveneck initially provided housing for Fred Ross, Sr., a place to hold meetings, and financial support. In 1952 Ross was assigned by Saul Alinsky to work in San José, and shortly upon arrival, he sought out Father McDonnell to help identify potential organizers, such as Guadalupe-parish member César Chávez. Ross’s community organizing techniques were based on door-to-door canvassing and house meetings. Volunteers such as Rita Chávez Medina (César’s sister), Herman Gallegos, and César Chávez went door-to-door in the Eastside’s crowded neighborhoods, over unpaved streets, registering voters and talking to residents about how to form a CSO Chapter. The community was ready, and the formational meeting took place at Mayfair Elementary School in 1952. Meetings were later moved to the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, where the CSO established its first offices, local campaigns were planned and organized, and volunteers were trained.

-

The CSO and Fred RossAccording to historian Gabriel Thompson, Fred Ross, Sr., was born to an affluent and politically conservative family from Los Angeles. He attended the University of Southern California, where he was exposed to politically liberal ideas. Ross wanted to be a teacher, but after his graduation in 1936, due to the Depression, he took a three-year term as a relief worker. He then became manager of the federally-funded Farm Security Administration (FSA) Arvin Migratory Camp for Dust Bowl migrants located near Bakersfield. He replaced the previous corrupt manager and tried to regain the workers’ confidence by forming a workers’ council and supporting a cotton strike. During his time at Arvin Camp, he met folk singer Woody Guthrie and listened to his songs of political protest. During WWII Ross worked for the War Relocation Authority in Cleveland, finding jobs and housing for Japanese Americans not placed in internment camps. After WWII, he returned to Los Angeles to work for the American Council on Race Relations, organizing “multi-racial unity leagues.” He led voter registration drives to force out racist local politicians and desegregate schools. His work contributed to the successful 1948 California State Supreme Court decision in Mendez v. Westminster. Ross also worked for Saul Alinsky’s Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF). In 1947 he was hired to promote Latino political power in Los Angeles. That same year, in Boyle Heights, a Los Angeles neighborhood with a large Mexican population, Ross formed the first chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which was established to protect the civil rights of Mexican Americans and foster political and civic engagement. Fred Ross approached social worker Edward Roybal and Antonio Rios, a union organizer with the United Steelworkers of America, with the idea of forming a community-based organization. In the IAF model, an outside organizer works with local leaders to create a democratic organization where people can identify their concerns and address them through direct action. Edward Roybal became the first president and main spokesman of the CSO’s LA Chapter. Building on the earlier work of mutualistas, church groups, and community associations, the CSO stressed voter registration and held citizenship classes to promote political involvement. They also addressed ongoing problems such as poor community services and discrimination in housing, education, and employment. After WWII, Mexican American and African American civil rights groups occasionally worked together, though they sometimes differed in their aims and goals. For example, education was an important issue for both groups, but bilingual education was extremely important to Mexican Americans, while busing was a higher priority for African Americans. Fair housing and employment legislation were key issues for both, but Mexicans prioritized pensions for resident non-citizens, who were often not eligible for social services. CSO members learned the importance of becoming activists in their own communities. By 1963, the CSO had 34 chapters across the Southwest, registering 500,000 new voters and helping over 50,000 Mexican immigrants obtain citizenship in California. In 1949, utilizing the community organizing skills of Fred Ross, Sr., and CSO volunteers, Edward Roybal was elected to the Los Angeles City Council. The first Mexican to win a seat since 1881, Roybal was later elected to Congress, serving from 1963 to 1993.

-

Fr “Mac” McDonnell and Guadalupe ChurchFather Donald McDonnell was a member of a group of Catholic priests, the “Spanish Mission Band,” who worked with Mexican farmworker communities. Initially Fr. McDonald served at St. Joseph Church in the Mountain View colonia (1947-1951), encouraging the formation of Club Estrella as well as a community credit union. In 1952 he moved to Eastside San José and introduced parishioners to non-violent community organizing strategies, urging them to address racial discrimination through action. Known as “Father Mac,” he was familiar with Ernesto Galarza’s writings and agricultural union organizing, and instructed parishioners on labor law, focusing on abuses of the Bracero Program. The Eastside had no Catholic church to serve the growing Mexican population, and Father Mac helped parishioners to establish the Guadalupe Chapel. In 1953, the Catholic Church purchased an old church building, disassembled it, and moved it to the Mayfair district. It was reconstructed by parish volunteers, including siblings César and Richard Chávez and their sister Rita Chávez Medina. The building housed the growing Our Lady of Guadalupe congregation until it was replaced in 1968. The chapel also served as the first headquarters of the San José chapter of the Community Service Organization (CSO), which trained community organizers and conducted campaigns for social justice and labor rights. Because of this history, Fr. McDonnell Hall, originally the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places (2016) and became a National Historic Landmark in 2017.

-

The American G.I. ForumWWII brought a new awareness of racial issues as the military began to integrate under Executive Orders in 1941 and 1948, though full integration would not come until 1960 for some branches. Anglo American GIs shared bunkrooms, meals, and social time with their Mexican counterparts and understood that they had to rely on one another in combat. Although Mexican Americans did not face the same level of segregation in the military as African Americans and lighter skinned Mexicans were sometimes classified as white, they understood that racial prejudice still remained. As Mexican veterans returned home, they continued the fight for the “Double V for Victory”–victory against racism abroad and at home. When Mexican American veterans were banned from participating in local veterans’ groups and denied services at veterans’ hospitals or military cemeteries, in 1948 they formed the American G.I. Forum, which welcomed all veterans of color. The GI Forum was founded in Texas by Dr. Hector P. García to fight discrimination against Mexican Americans in employment, education, and access to veterans’ benefits. The organization gained national attention when it took up the Felix Longoria case in 1949. Longoria, an ethnic Mexican veteran from Texas killed in the Philippines, was refused burial in his hometown, Three Rivers, Texas. The GI Forum appealed to then-Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had seen discrimination first hand in Texas after teaching in a segregated school for Mexican Americans. In the Longoria case, Johnson intervened, arranging for him to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors at no cost to his family. The San José chapter of the Forum was formed in 1949, focusing on youth issues and offering scholarships. In 1960, the Forum collaborated with other groups, such as the Community Service Organization (CSO), on voter registration campaigns and advocating for ethnic, minority and disenfranchised communities.

-

Legal Challenges to SegregationSchool segregation was a major issue for Mexicans in California and Texas. Groups of parents filed numerous lawsuits to push local governments to integrate local schools. These struggles united parent groups and LULAC (The League of United Latin American Citizens), and together they fought landmark cases such as Del Rio ISD v. Salvatierra in Texas (1930) and Roberto Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District, often referred to as “The Lemon Grove Incident,” in San Diego, California (1931). LULAC, the first national Mexican American Civil Rights organization, was established in 1929 by American citizens of Mexican descent in Corpus Christi, Texas. Until WWII, LULAC undertook several school desegregation court cases in Texas and California using the argument that Mexicans were white. Accordingly, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) gave American citizenship to Mexicans living in the U.S. territory at the end of the Mexican American War while the U.S.Constitution had stipulated that only white males were eligible for U.S. citizenship. This legal argument was not successful. After WWII, LULAC worked with the Mexican consulate and the NAACP to strategize for Mendez v. Westminster (1947). This California Supreme Court case repealed all segregation in California schools, arguing that the 14th Amendment provided for “equal protection” under the law, and influenced the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education Topeka, Kansas. In 1954, lawyers from the American G.I. Forum and LULAC argued in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Hernandez v. Texas that the Mexican American defendant was denied “equal protection” under the 14th Amendment. The court granted that Mexican Americans were “a class apart,” not easily fitting into a legal structure that only recognized blacks and whites. Direct action on segregation, including strikes, walkouts, and boycotts, would come much later.

-

Ernesto Galarza NFLU and The Bracero ProgramThrough his research, Galarza came to understand that one of the major obstacles to unionizing Mexican farmworkers was the 1942 Mexican Farm Labor Program Agreement, better known as the Bracero Program. He left the Pan-American Union outraged by their acceptance of U.S. corporations’ exploitation of Mexican labor. In 1947 he became the director of research and education in California for the AFL-CIO’s National Farm Labor Union (NFLU) previously known as the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, which included black and white tenant farmers and agricultural laborers who organized for better wages, working conditions, and favorable legislation for small-scale farmworkers. In 1948 Galarza became vice president of the NFLU and was deeply involved in over a dozen unsuccessful strikes between 1947-1954, including tomato pickers in Tracy, cantaloupe pickers in Imperial County, and at the DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation. Outside of California, he organized sugar cane workers and strawberry pickers in Louisiana. In 1952 NFLU became the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), and Galarza became its secretary from 1954-1963. Strikes were impossible to win because braceros would replace strikers as strikebreakers, and Galarza left labor organizing determined to use his writing skills as a weapon to help end the Bracero Program. Galarza had visited bracero camps and saw firsthand how employers used braceros to break strikes and avoid union organizing. Bracero labor also depressed wages for American workers. Galarza exposed abuses within the Bracero Program in his best-known work, Merchants of Labor (1964), which helped to end the program and laid the groundwork for César Chávez to begin the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA) in 1965. Galarza became a labor organizer because he believed that to achieve civil rights, Mexican Americans and labor unions needed to work together to address workplace and community problems. Between 1963-1964, Galarza served as advisor to the U.S. House Committee on Education and Labor. In 1979, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature for his writing on braceros.

-

Ernesto Galarza’s BackgroundDr. Ernesto Galarza was born in 1905 in the village of Jalcocotán near Tepic, Nayarit, México. In 1911, he came to the U.S. with his mother and uncles to escape the Mexican Revolution. After losing his mother and uncle to influenza, Galarza lived in the Sacramento barrio working as a farm laborer. His surviving uncle made it possible for him to continue his education. At age eight, he knew more English than the adults in the labor camp and became a spokesman for them, highlighting their poor living conditions. Galarza understood that education was essential and to finance his schooling, took jobs as a messenger, clerk, court interpreter, and field and cannery worker. He would later chronicle his childhood in the autobiographical novel Barrio Boy, published in 1971. Encouraged by his teachers, Galarza entered Occidental College in Los Angeles on a scholarship in 1923. After completing his B.A., he obtained an M.A. in history from Stanford University and then in 1944 a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University. While at Columbia, Galarza worked for the Pan-American Union (1936-1947), serving as chief of the Division of Labor and Social Information. Although he left this job to become a labor organizer, Galarza was viewed as an intellectual and scholar whose weapons were words. Recognized as a poet, author, and educator in his later life, he taught at every level from elementary school to university and was a lifelong advocate for bilingual education.

-

Mexican Cannery Worker Unionization, 1917-1960The first Santa Clara County cannery strikes took place in 1917 with the AFL’s Toilers of the World. According to historian Glenna Matthews, the Toilers signed a two-year contract that only benefitted male workers. Not until the 1930s did women cannery workers find a union voice. Initially, cannery and field/orchard work were seen as components of the larger agriculture industry and excluded from government-sponsored protections afforded to industrial workers under the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) or The Wagner Act. By the 1930s, as more mechanization was introduced, cannery and packinghouse labor gained protections offered to industrial workers. According to historian Glenna Matthews, canners strengthened their efforts to fight unionization during the 1930s with the formation of the Canners’ League. The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act stipulated that competing companies within an industry should cooperate, which the fractured growers resisted. During the Great Depression, Santa Clara County canners faced a harsh economic future. Profit margins were dropping, executives took pay cuts, and small canners went out of business. According to historian Glenna Matthews, during that decade CalPak reduced production by one third. Processors tried to reduce expenses by lowering workers’ pay. With the first dramatic decrease in wages, in 1931 cannery workers fought back with their first strike under the Cannery Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU). Dorothy Ray Healey and Elizabeth Nicholas were among the organizers, with Dorothy taking the lead with cannery workers. A few months prior to this strike, Italian and Spanish cannery workers formed the American Labor Union and revealed the harsh conditions cannery workers faced. In 1931 the CAWIU set up picket lines at several canneries. Workers were arrested, and in July 2,000 workers held a rally in St. James Park, demanding that police release jailed picketers and triggering the worst riot in San José history. In response Richmond-Chase cannery set up machine guns at its gate, and CalPak threatened to ship its fruit to distant canneries. The strike was lost, and the CAWIU shifted its focus to unionizing agricultural workers. The 1931 cannery strike developed future cannery union leaders who joined the struggle for worker representation led by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The AFL was seen as a “company union,” not taking the grievances of cannery workers seriously, particularly those of Mexican women. At the end of the 1930s, the AFL battled the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) for cannery worker representation and won the struggle. By the end of the 1930s, all San José canneries were unionized and remained so until the last one, Del Monte Plant #3, closed in the 1990s, with union representation shifting back and forth. In 1945 the AFL relinquished its control of Santa Clara County cannery workers to the Teamsters, who neglected the rights of non-white cannery workers. Union representation returned to the AFL, which merged with the more left-wing CIO in 1955. By the 1950s many Mexican cannery workers had gained unemployment insurance, a livable wage, and benefits for the first time. In 1967 under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, jobs could no longer be classified as “male” or “female,” so women could enter the more lucrative warehouse jobs previously controlled by men. Through the unions, Mexicans were able to earn the salaries needed to settle permanently in the colonias and become homeowners.

-

Mexican Farm Worker Unionization, 1930-1960During the Great Depression, ethnic Mexicans viewed labor organizing campaigns as part of the promise of equality and civil rights. During this time, Santa Clara County saw some of the most significant agricultural strikes in the U.S., many involving Mexican workers. Before WWII, most Mexicans worked on farms in the fruit and nut orchards or tomato and pea field/row crops. The Depression of the 1930s saw a deterioration in working conditions and a dramatic decrease in pay for orchard and field workers, who were paid by piece work rather than hourly wages. Historian Glenna Matthews claims that weekly pay dropped from $16.33 in 1929 to $8.04 in 1933. Growers stopped working cooperatively in the fruit exchange and began selling their crops individually, competing with each other and lowering wages even further. During the New Deal, between 1933 to 1937, the federal government supported farmers by buying their crops, thus propping up prices. In 1931 the new Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) set up its state headquarters in San José at 81 Post Street, charging monthly dues of twenty-five cents for the employed and five cents for the unemployed. Dorothy Ray Healey, Elizabeth Nicholas, Pat Chambers, and Caroline Decker were among the CAWIU organizers working in the county. The CAWIU undertook thirty-seven agricultural strikes in California. Historian Glenna Matthews contends that Santa Clara County, as in the rest of the nation, saw more strikes and violence in 1933 than ever before, with three agricultural strikes and one brutal non-agricultural-related lynching. In April of 1933, 2,000-3,000 pea pickers, composed of Mexicans and Dust Bowl migrants working near the Milpitas/De Coto County line, struck for higher wages and lost. In June 1,000 cherry pickers, mostly Spanish workers from the Mountain View area, struck for higher wages. That same year, the cherry picker strike was considered the most violent of the three strikes in Santa Clara County. Workers were successful and won a 50-percent raise, from twenty cents to thirty cents an hour. According to the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee Report (1936-1941), the cherry pickers were successful because the Spanish workers were homeowners and had invested in their communities, unlike the migrant Mexican and Dust Bowl pea pickers. In August 1933 pear pickers staged a strike, CAWIU’s most successful strike in the County, largely due to organizer Caroline Decker, who gained the support of the Palo Alto Democratic Club. In turn the Democratic Club, state and federal government officials, and the California Bureau of Labor Statistics backed the union’s right to picket, opposing the growers who had obtained an injunction against picketing workers. The Bracero Program made it difficult to organize farmworkers throughout the Southwest, as well as Santa Clara County, because braceros were used as strikebreakers until the program ended in 1964. Ernesto Galarza organized agricultural strikes (though not in Santa Clara County) using the National Farm Labor Union during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1937, workers in thirteen dried fruit companies decided to unionize. They organized the Field Practice Group and initially contracted with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), considered a “company union” less concerned with non-white members, who represented 98% of the dried fruit workers of Santa Clara County. Unlike cannery workers, in 1941 dried fruit workers left the AFL and voted for representation from the more left-wing CIO, which promoted for the largely Mexican workforce higher wages, retirement benefits, and a hiring hall instead of a shape up.

-

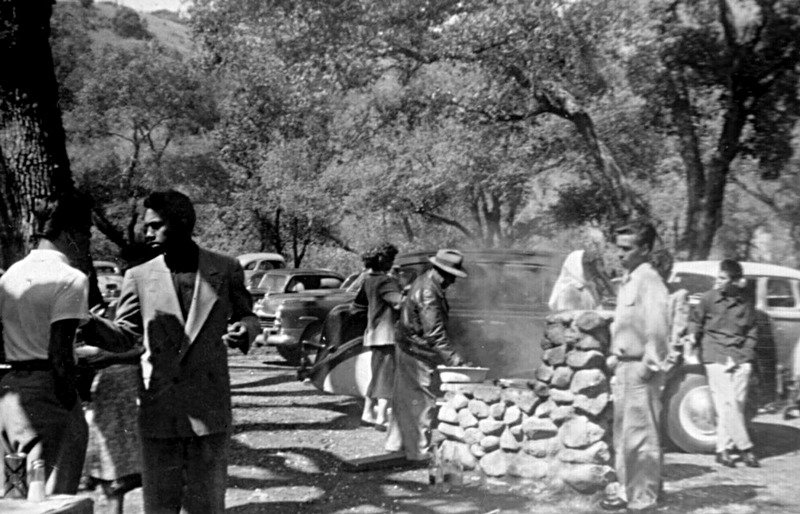

Recreation at Parks, Churches, Beaches, Mountains and BeyondLocal parks were popular sites for large family gatherings and youth activities. During the post-WWII period, there were few parks or recreation centers in Mexican neighborhoods. Families might host small groups at home but had to travel to parks like Alum Rock to host larger groups. With the lack of neighborhood parks, the Catholic church often filled the gap by providing a place for recreational activities and community events. Catholic churches became important public spaces, with social halls used for family or community events, art programs, English classes, and neighborhood meetings. Leaders in these Catholic churches often moved on into positions of influence in labor movements and political organizations. While the majority of ethnic Mexicans in Santa Clara County identified as Catholics, there were also Mexican Baptists, as well as Presbyterians, Methodists, and various evangelical denominations. While Mexican cultural traditions were acknowledged, many churches sponsored youth baseball and basketball teams in order to engage immigrant families in American culture and recreation. Neighborhood schools also offered organized sports. During the post-war years, automobiles became more affordable, and families began to travel longer distances to the beach and Boardwalk in Santa Cruz, to camp or hike in the redwoods or Mt. Hamilton, tour San Francisco, or even vacation in México.

-

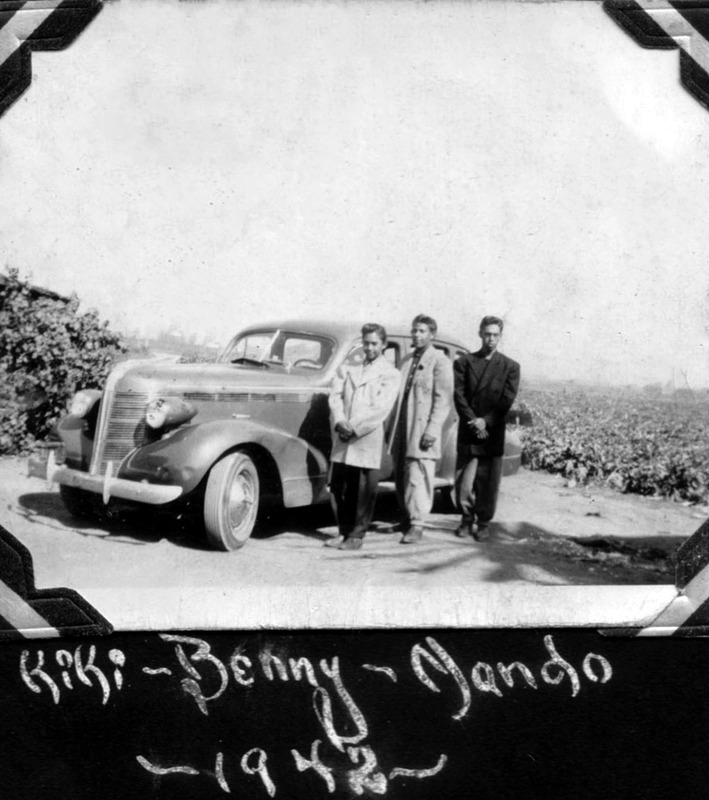

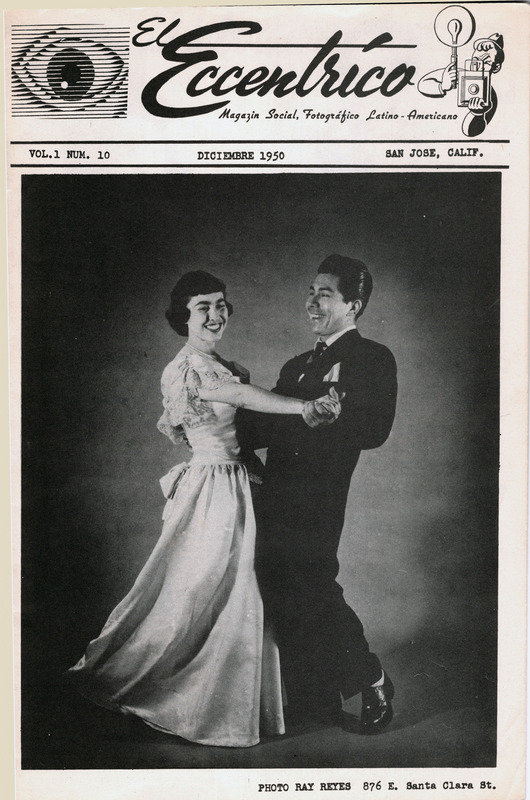

Leisure Time with Social and Car ClubsWith non-agricultural jobs increasingly becoming available to ethnic Mexicans after WWII, more Mexican American youth began to attend high school and college. In the 1950s, a proliferation of social clubs, like Club Cuauhtémoc, provided a place for young ethnic Mexican urban professionals to gather. Some social clubs functioned similarly to town clubs, like The Del Rio Club, bringing together people from the same town or region. Some social clubs focused on public service, holding fundraisers for charitable causes or organizing around community issues such as voter registration and Latino candidates. Social clubs sponsored dances, such as the traditional formal Black and White Ball, organized outings such as picnics, or group activities, including bowling teams. In the 1950s and later, lowriders in San José were mostly Latino, converting older cars for cruising, car shows, and design competition at events, adorning their cars with Mexican American imagery and vibrant colors. As small groups organized into regional clubs, lowriding became a multigenerational cultural activity, with the embellished car club jacket created to identify the local group. These “jacket clubs” were popular in San José, though local police banned them from 1986 to 2022 on the basis of preventing gang violence and related crime. The intersection of Story and King in the Eastside is now recognized as the meeting ground for generations of Lowriders and San José as a center of Lowrider culture. As the Mexican American community became more established, new organizations were formed, such as the Mexican American Chamber of Commerce and the Mexican Masonic Lodge. The number of social clubs, ethnic organizations and fraternal associations increased among the post-WWII growing Mexican middle class and young professionals, who announced their activities regularly in the bilingual, regional entertainment magazine El Excentrico (FKA El Eccentríco). Church groups, clubs, and organizations were also involved in charitable activities and community projects. Social clubs, sporting events, baseball and basketball clubs, and car clubs promoted ethnic consciousness, built solidarity, and sharpened organizing and leadership skills. They offered young Mexican Americans opportunities to compete on an equal basis outside the immigrant community. Such cultural activities generated networks, created bonds of solidarity, and provided a strong foundation for the Mexican civil rights movement to emerge within a flourishing community of musicians, artists, sportsmen, and club members.

-

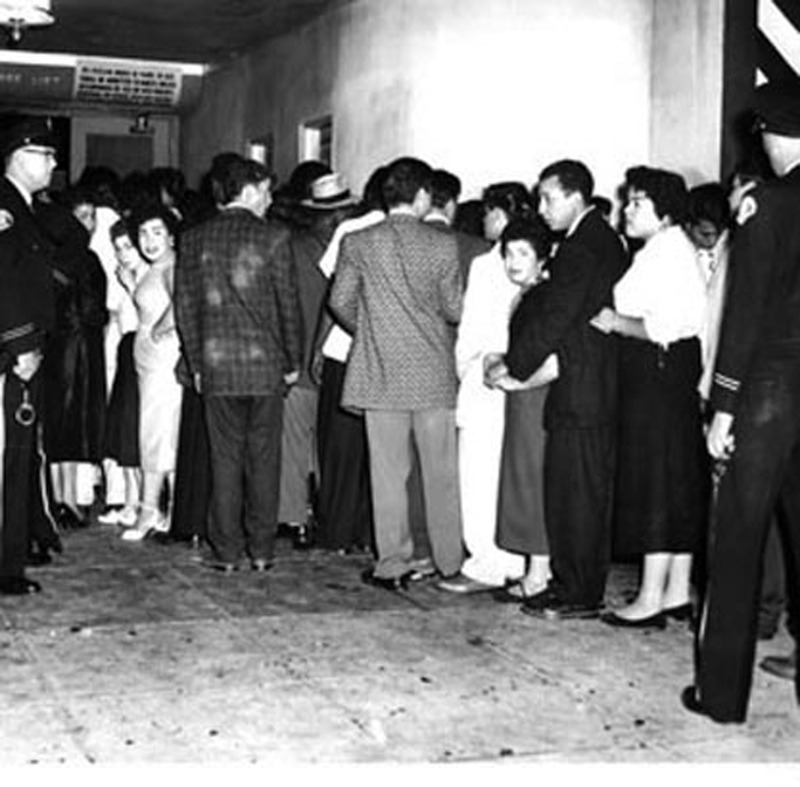

Rock and Roll Riot of 1956Few people have heard about what became known as the first Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot at The Palomar Ballroom on the night of July 7, 1956. Opened in 1947, the Palomar was the first integrated ballroom in San José, where big bands, vocalists, and jazz artists from across the country, México, Latin America, and the Caribbean performed in front of an integrated audience. In 1956, Rock 'n' Roll was still new, and the big attraction that night was the now legendary Fats Domino, who arrived very late to a large crowd inside the ballroom and hundreds waiting outside. By the time the band started, some patrons were already drunk and unruly. During the intermission, beer bottles were thrown; then a brawl began as lights were smashed, chairs and tables destroyed, and many were injured. Nearly a dozen people were arrested. Accounts of the brawl appeared in every major newspaper in the country, and the San Francisco Chronicle termed the affair a “Rock ‘n’ Roll Riot,” linking the music with the breakdown of public order. One week later the San José City Council considered a resolution to ban rock and roll at city-owned venues, eventually establishing a new ordinance requiring all drinks at concerts to be dispensed in paper cups. Just as the zoot suit had been used to criminalize youth of color in the 1940s, Rock ‘n’ Roll music was used to vilify another generation of ethnic young people.

-

San Jose’s Zoot Suit RiotsThe Zoot Suit Riots in 1943 were a series of violent clashes in Los Angeles between U.S. servicemen, off-duty police officers, and civilians who confronted young Latinos and other minorities. The riots took their name from the baggy zoot suits that accentuated their movements worn by many young men in the 1930s in dance halls in the East. The zoot suit became a popular trend among young men in African American, Mexican American, and other minority communities in California. Anglo Americans knew very little about the Mexican American community, who were generally portrayed by local police and newspapers as problematic lawbreakers, drunks, or criminals. Young Mexican Americans were portrayed as pachucos (juvenile delinquents) or gang members who posed a danger to society. Conflicts between police and Mexican youths spread from L.A. to the Bay Area during the summer of 1943. In San José police carried out a similar harassment of Mexicans in the name of “keeping the peace.” In one instance, “intent on starting their own ‘zoot suit’ war,” a group of sailors hunted down Mexican youths as they spilled out of the downtown dance halls and ballrooms on Market Street in the late hours of the night. Local Judge William James stated, that "we certainly don’t want to see anything happen here like it is in Los Angeles,” handing down probation if the arrestee would join the military. Large groups of assembled Mexican young men were often considered suspect. One night, two San José police officers tried to arrest two Mexicans having a fist fight in St. James Park. The two escaped but were caught in front of a dance hall where a group of Mexican cannery workers and zoot suiters were just leaving. The group attacked others, who followed the officers and the youths back to the police station. When the youths fell and appeared injured, a large group of military and local police arrived to disperse the crowd. At a local Santa Cruz beach, Marines drove visiting Mexicans away. Five Mexican young men were held in the San José Jail “because of their large size.” In 1944, 25 zoot suitors were arrested for “frequenting streets and public places in the late night,” and three of what the San José police considered “bad boys” were deported to México. That same year, Gilroy police arrested thirty Mexican youth “for violating curfew laws.” Toward the end of the War, another clash occurred between zoot suiters and sailors in St. James Park, the same location as the lynching of Tiburcio Vásquez in the late 1800s, ending with the arrest of the Mexican youths and release of the sailors.

-

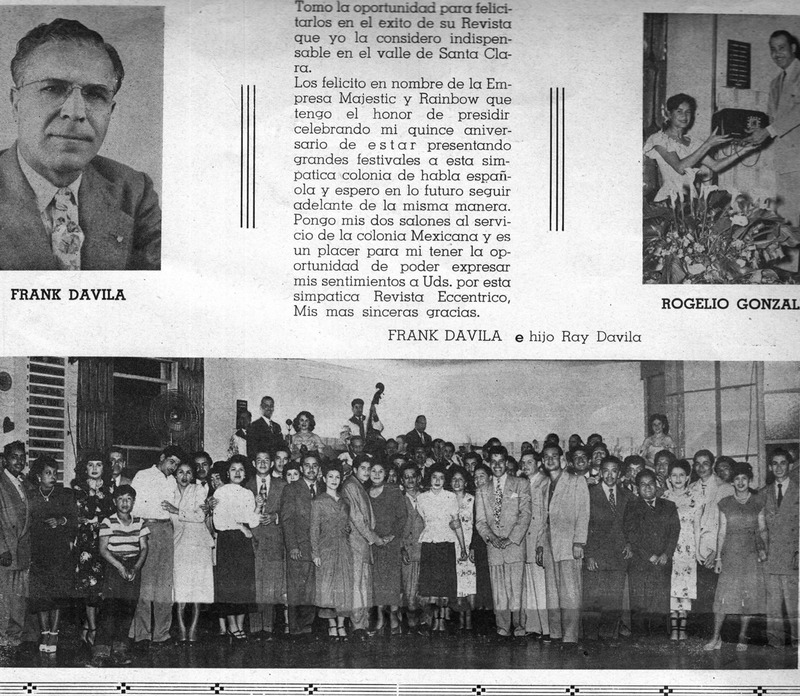

Mexican Dancehalls, Lounges and BallroomsPublic dance halls in the U.S. first appeared in urban areas around 1845, often as dance halls associated with the working classes, selling liquor or operating as saloons. In polite society, public dances were charity events, club or lodge dances, and held at dance palaces or pavilions associated with amusement parks. Providing a new social setting where people could make new acquaintances and socialize with those of diverse backgrounds, while observing the latest trends and fashions, ballroom dancing altered social patterns between the sexes, different social classes, and different racial and ethnic groups at the turn of the 20th century. With the growth of popular music and dancing came new neighborhood dance halls or private clubs. Public dance halls and pavilions, often offering dancing lessons, did not appear in local city directories until 1927. From 1927 to 1945, four main ballrooms were located in downtown San José: The Balconades on Santa Clara Street, The Rainbow Ballroom on San Antonio Street, The Majestic on Third Street, and The Palomar Gardens on Notre Dame Street. These offered music by varied racial/ethnic bands in front of an integrated audience, although a majority came from the same racial/ethnic group as the band playing. In 1946, two other local venues were added: The Italia Hall, operated by Prospero G. López, and The Townsend Hall, owned by Frank and Angelo Boitano. These informal settings often catered to the non-Anglo working class and ethnic communities who could not afford, and often were not welcome, in the major ballrooms. In the late 1950s, John Zamora, a local Mexican businessman who had grown up as a farmworker and then went on to college, opened several restaurants with lounges where his musician brother Bobby Zamora and his band performed. Music producers, such as Frank Davila, understood that the availability of both radios and record players to a wider audience helped to popularize new artists and sell records. While lounges and nightclubs offered an audience of 300-500 each night, large ballrooms might attract 3000-5000 potential record buyers. These large venues were ideal for aspiring performers and big-name attractions with new albums. During the 1930s, large public dances and concerts were held at The San José Municipal Auditorium, offering traditional Mexican and “Spanish-American” music. According to public historian Suzanne Guerra, who did an historical context on the last surviving ballroom from the Big Band Era, The Palomar, constructed in 1946, was the only venue where an integrated audience could attend social dances and musical concerts in an elegant setting. San José provided numerous performing venues. Although not as large a market as Los Angeles, the proximity to the Bay Area and the many small venues in Santa Clara County enabled musicians to supplement jobs in the canneries with weekend performances at dance halls and clubs. This was the experience of Francis Pacheco Wells, vocalist for Dan's Combo, performing on the weekends at Maria'a Cocktail Lounge (728 N. 13th St. San José). Family celebrations and community fundraising events were often held at ballrooms and public halls. Musical parties like the multigenerational tardeada reinforced family and community ties, with both traditional musical styles and contemporary music, food and entertainment for largely Spanish-speaking audiences. In this way, the mix of musical styles in San José was continually renewed with each wave of immigrants and their distinct musical traditions.

-

San José Sabor: Local Mexican Musicians, Singers, Bands and Radio Stations in San José, WWII to 1960San José gave rise to several nationally recognized musicians and singers, such as the Montoya Sisters from the Eastside. From the 1940s through the 1960s, Agustin De La Grande was an important performer who, through his Academia de Musica, mentored many aspiring local musicians and young people in his marching band and orchestra. Agustin taught his daughter Trinidad De La Grande Martínez as well. She learned to play several instruments and filled in positions in her father’s band when needed. Some of De La Grande’s students went on to form their own groups, like the Bernie Fuentes Band, the house band at the Palomar. Low pay for performances forced many musicians to work during the day, many in the canneries, and perform in the evenings after work. This was the experience of musician Coronado Barrientes, drummer Rudy Coronado, and singer Francis Pacheco Wells. By the 1950s, young Mexican Americans, like their peers, were attracted to the new musical styles of rhythm and blues and rock-n-roll. During this time, radio was becoming the prime source of Spanish-language entertainment and information for the expanding Mexican colonias. Many ethnic Mexicans could not afford to buy records or attend concerts, but they loved listening to music in public spaces that had jukeboxes or on the radio. Several local radio stations developed Spanish programs, some of which were broadcast by Jesus Reyes Valenzuela, born in Shafter, Texas, and the first Spanish language broadcaster to operate in Santa Clara County. In the late 1940, his "Hora Artistica" was aired on KSJO Monday through Saturday. Mornings and afternoons featured the beloved singers of Mexican rancheros--Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Luis Pérez Meza, Luis Aguilar, and Lola Beltran. Radio Station KAZA in Gilroy started in the 1950s or 1960s. It was Portuguese owned and had 80% Spanish language programming, 7% Portuguese language programming and the remainder was English programming. In the 1960s, radio stations began to feature live remote broadcasts from community events featuring local singers and musicians.

-

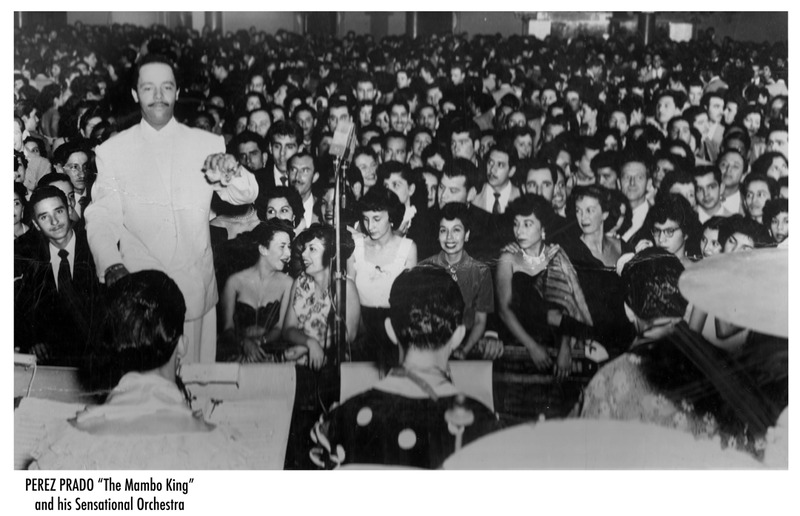

The Influence of Mexican Music on San José, WWII to 1960In 1942, the U.S. government instituted the Emergency Farm Labor Program, known as The Bracero Program, bringing in a new group of immigrants from the border regions along with a new style of music called Norteño or Tejano. The musical traditions of the Tejanos of South Texas and Norteños of Northern Mexico have been influenced not only by the mother country, México, but also by their Anglo American, African American, and immigrant neighbors like the Czechs, Bohemians, and Moravians as well as the Germans and Italians. From these influences came the polkas and accordion music that are so closely associated with this style. Many of these Mexican immigrants were from rural areas, and more familiar with the Mexican orquesta tipica, or string band, and regional music from their homelands, such as the conjunto. The conjunto mixed the folksy storytelling corrido, the dance form huapangos, and the traditional ranchera with European instruments such as the accordion. In the borderlands of the American Southwest, the orquesta Tejana was patterned after the big bands of this period and appealed to an acculturated Mexican American audience. A fusion of these styles with mariachi and rock-n-roll in the late 1950s would result in a new style referred to as Tejano or Tex-Mex. Mexican corridos, a popular music genre of the late 1920s to the mid 1940s, provided a way for ethnic Mexicans to document their immigration, migration, work and day-to-day living experiences. Frontera music curator Juan Antonio Cuellar notes that corridos were a form of oral history documentation adapted to music. News headlines became corridos stories. Cuellar describes corridos as “the newspapers of the Mexican working class”. During the 1920s, Latin American music and performers became popular among elites of all continents, who often preferred simplified romantic ballads and Latinized American pop music. Both this “society rumba” and Afro-Cuban influenced Latin American music such as mambos, were popular with local Latino audiences for the next several decades. Out of the big band era arising in the mid 1930s through the 1940s, Mexican musicians added a Mexican twist and created Pachuco Boogie. The largest events in San José were often held at the Municipal Auditorium, with performers such as Tito Puente, Desi Arnaz, and Lalo Guerrero playing for dances. Other ballrooms included The Balconades and The Palomar/Starlight ballrooms. During the war years, big bands–such as Benny Goodman, Glen Miller, Xavier Cugat, Jimmy Dorsey, and Artie Shaw–all featured Latin songs. In the early 1950s, American bands playing the Latin rumba, including nightclub performers such as Xavier Cugat, Desi Arnaz, and Carmen Miranda, were often featured in movies and television.

-

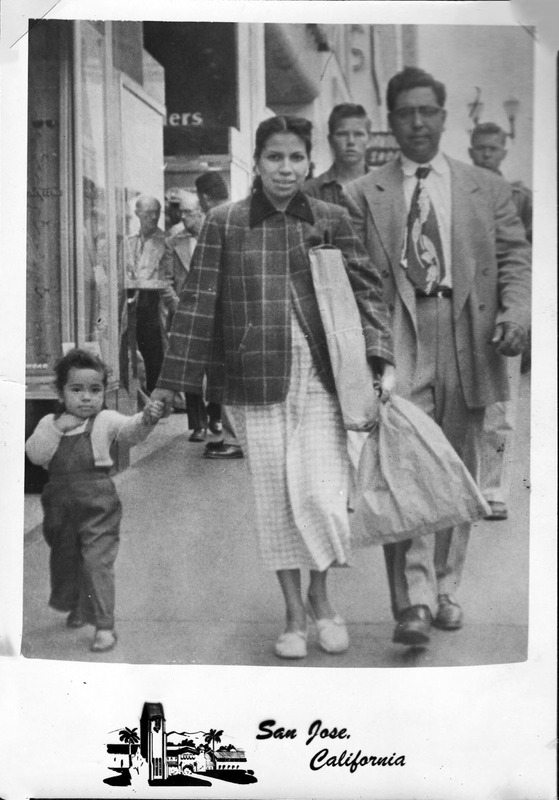

Mexican Entertainment in Downtown San José, WWII-1960Downtown San José was the regional social hub for Mexican residents. On weekends, locals were joined by farm workers from nearby rural regions of the San Joaquin Valley to eat at a Mexican restaurant, watch a Spanish-language movie, meet friends for a drink, or go dancing. On Market Street a strip of restaurants and stores catered to a Mexican clientele. After WWII, the Liberty Theater, the Victory, the Lyric, and the José offered first-run movies from México and staged personal appearances from singers and performers. Local ballrooms (see ballroom section) also enlivened the downtown social scene. The proximity of nightclubs, many Mexican restaurants and shops that encouraged their patronage, was a major draw to those who had only limited services in their small communities or the work camps scattered throughout the region. After WWII El Eccentrico, the local Spanish-language entertainment magazine, established in 1948 (running until 1980), carried ads for shops, grocers, restaurants, and real estate and insurance agents catering to a Mexican clientele. Alongside the ads were announcements of clubs, concerts, and community events.

-

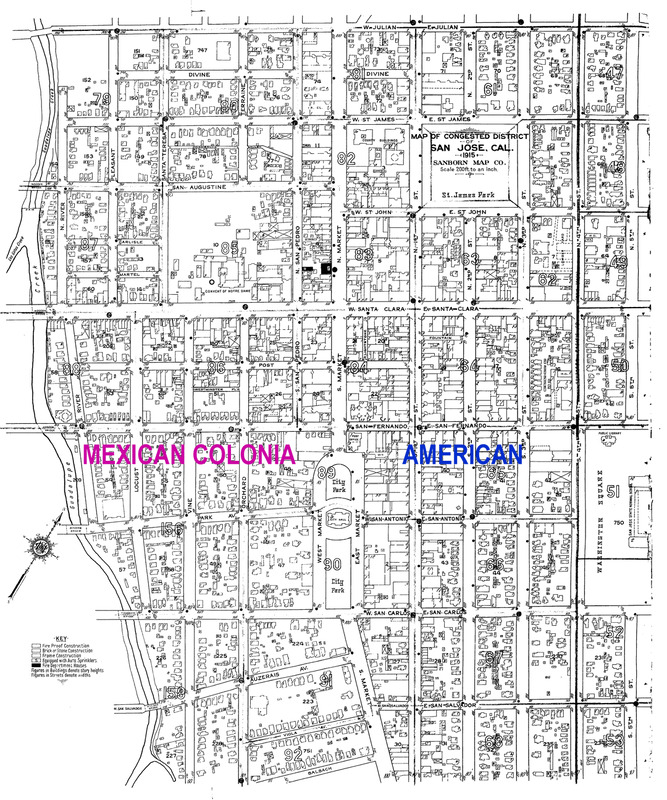

Mexican Businesses in Downtown San José, WWII to 1960Historically, American settlement was concentrated east of the old Pueblo, with new businesses on 1st, 2nd and 3rd Streets. The ethnic Mexican residents of Santa Clara County considered Market Street the line between the American area and the Mexican Downtown Colonia. Restrictive housing policies had created segregated neighborhoods, and it was commonly understood that public accommodations were racially restricted until the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Stores, restaurants, bars, and shops that served Mexican customers were located on Market Street or the portions of 1st, 2nd, or 3rd Streets south of Santa Clara Street. On weekends, Mexican workers from across the County congregated to do their weekly shopping, see a movie, or get a haircut. By 1960, Mexican Americans and Mexican nationals comprised one-fourth of Santa Clara County’s population and were a major factor in the regional economy. Urban redevelopment and freeway construction would displace a large number of residents of the Downtown Colonia, contributing to the closure of many Mexican businesses in the area.

-

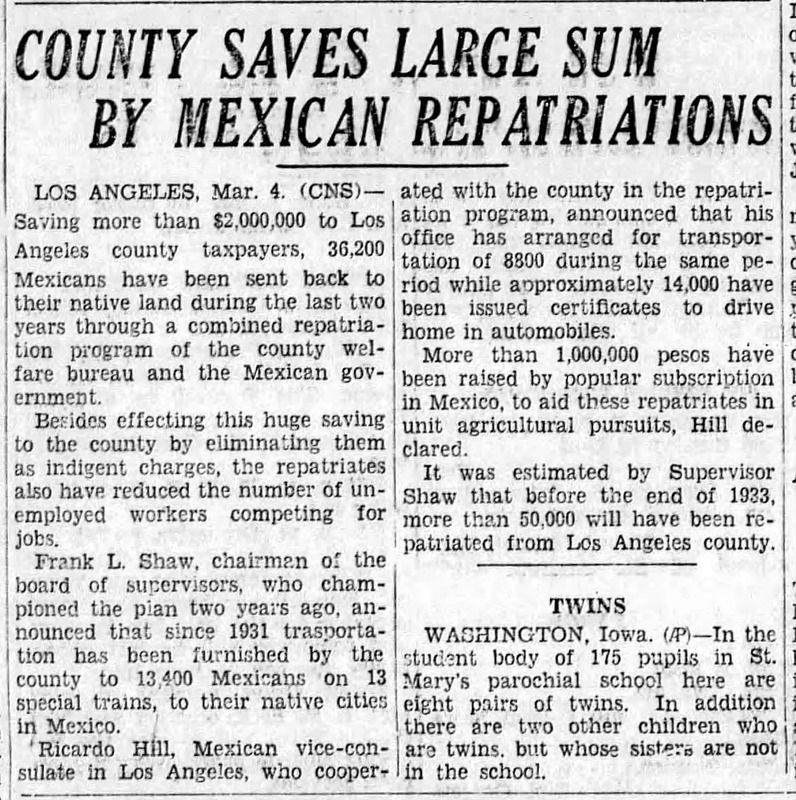

The 1930s Deportation/Repatriation Campaign in San JoséIn Santa Clara County, Mexicans did not endure the same threats from the Klu Klux Klan that their compatriots in Southern California experienced in the 1920s. However, with the 1924 Immigration Act, pressure was put on the U.S. federal government to establish the first Mexican border patrol. In Southern California, the Mexican Deportation Campaigns from 1929-1934 further limited immigration. Santa Clara County, however, did not conduct extensive deportation campaigns, although Anglo trade unions tried to do so during the Great Depression. Instead, the Mexican consulate promoted the idea of repatriation to México to help those Mexican nationals who were suffering from the economic fallout from the Depression. As non-citizens, this population was ineligible for state or federal aid. During the 1930s, according to History Unfolded, 400,000-1 million of the nearly two million Mexicans living in the U.S., including American citizens, were either deported or repatriated to México. In San José, one third of the 4,000 Mexican residents chose to return to México in the Mexican government sponsored repatriation campaign.

-

Mexican Mutualistas, Home Clubs and La Comisión Honorifica in Santa Clara CountyIn Santa Clara County, immigrants formed associations with others from their original home in México or other regions of the Southwest. In San José, historian Stephen Pitti describes the rise of “town clubs” as the fraternal twin of the Mexican American mutualistas, or mutual aid societies. One important difference was that both men and women joined the town clubs while mutualistas were for men only. In the late 1920s, town clubs and mutualistas both helped with life insurance and funeral expenses for those without funds, fostering “a sense of local identity” while maintaining cultural and nationalist connections to México. Town clubs linked transplanted Mexican residents from similar hometowns that were now living in Santa Clara County. These community organizations assisted families, developed community and promoted cultural events. They held social activities in local parks and residences to raise money to aid members and celebrate cultural ties, such as Fiestas Patrias. Most importantly, they advised newcomers in their native language on local laws, customs, and practices to help them integrate into American society. While Americanization programs were designed to replace immigrants’ native tongue and cultural traditions, town clubs and mutualistas aided immigrants in their transition to the new country. Mutualistas and town clubs strengthened links to the Mexican consulate and to México as well. Using these connections, the consulate encouraged repatriation to México for San José immigrants struggling in the U.S. during the Great Depression. The Mexican consulate in San Francisco worked with the mutualistas to promote Mexican national celebrations of the Fiestas Patrias and to aid Mexican citizens. During the Great Depression, the town clubs grew because it was impossible to afford annual visits to México as had been common in the 1920s. The California deportation campaign against ethnic Mexicans between 1929-1934 reinforced Northern California Mexicans’ reliance on their town clubs. Prior to WWII and after, non-citizens were usually ineligible for social services. Mutualistas played an important role in redressing these inequities, advocating for their members with police and immigration authorities and granting small loans, as well as sponsoring local sporting events and cultural celebrations. The Mexican Consulate established the Comisión Honorifica Mexicana, an organization to promote cultural connections and aid Mexican citizens in the United States. The Comisión admitted all men of Mexican descent, regardless of citizenship.

-

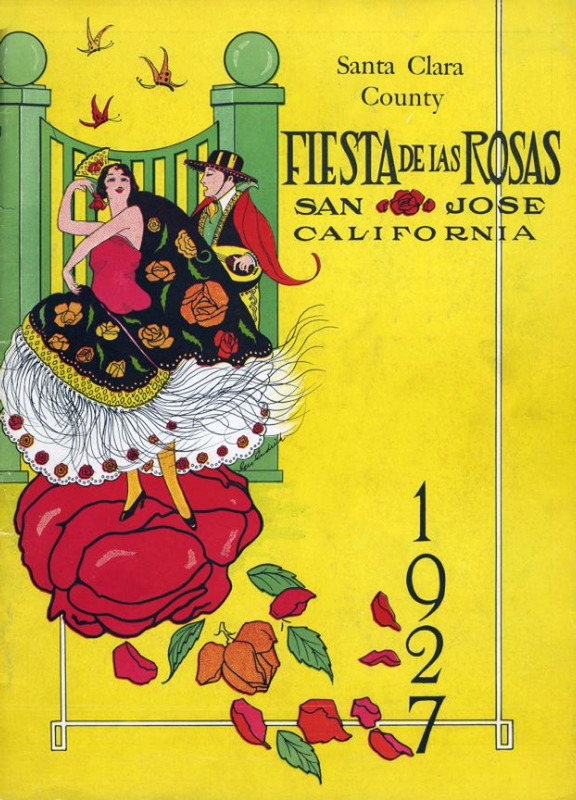

Mythologizing the Past While Discriminating in the PresentIronically, in the 1920s and 1930s, at a time when Mexicans were being pushed to the economic and geographic periphery of San José, Anglo city boosters promoted a parade, Fiesta de las Rosas, celebrating the region’s so-called Spanish (European) or “civilized” history. The event started as The Rose Carnival in 1896 and became the Fiesta de las Rosas in 1926 and lasted until 1933. In this instance, as historian Stephen Pitti notes, Anglo citizens connected their shared European white heritage with an imaginary Spanish-European California, an explicitly non-Mexican past. A few of the region’s remaining Californios were considered worthy of celebration, such as Santa Clara’s Encarnación Pinedo. Historian/journalist Carey McWilliams observed that the Anglo population considered these particular Californios to be the living embodiment of the “Spanish fantasy heritage.” During the 1910s and 1920s, fiesta parades took place throughout California and were wildly popular, particularly in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara; some continue on today. Celebrations and theatrical performances using the themes of California’s mythical past were held throughout California in plays like “The Mission,'' by John S. McGroarty. Santa Clara County hosted its first performance of “The Mission'' in 1915 at Santa Clara University. As PItti states, concerns over racial miscegenation and inter-racial romance were followed by two Fiesta plays that celebrated European White (Spanish or English) conquest over Mestizos and Indians, “La Rosa del Rancho, a Love Story of Early San José” (1927) and “The Madonna of Monterey” (1930). Anglos and ethnic whites played all the Spanish roles. For the audience, these celebrations affirmed the dominance of white European culture over the darker skinned Mexican “peons,” who were securely marginalized.

-

Community Segregation PoliciesSimilar to Southern California, ethnic Mexicans were subjected to social, residential and educational segregation throughout Santa Clara County. According to a 1950 SJSU student study and a 1978 study done by the Garden City Women’s Club, ethnic Mexicans, African Americans and Asians experienced de facto segregation in policies regarding public pools, bowling alleys, and ballrooms and dancehalls. Santa Clara County followed California’s segregationist housing policies, which also aligned with school segregation patterns. According to California law, segregated schools were built if a community had more than ten students of Native American, Chinese, Japanese or Mongolian ancestry and if these minority students’ parents petitioned a district to build one. If the community had less than ten non-white students, these students would only be allowed to attend the community school if white parents approved. If not, then these non-white students could not attend school. Students of Mexican ancestry were not included in California’s school segregation laws until their numbers increased by 1910 due to the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) pushing people out of México and the need for agricultural labor pulled Mexicans to the U.S. Since many ethnic Mexican families migrated to new jobs every two to three months following the crops, their children’s school attendance could be sporadic. At that time, schools were divided between elementary (K-8) and high school (9-12). Since few employment opportunities existed outside of agriculture before WWII Mexican children were encouraged to work in order to supplement the family income or drop out of school after the 8th grade. After WWII, educational opportunities changed for ethnic Mexicans. Young people began attending high school and college, and skilled, higher paying jobs opened up to them. In post-war California, attitudes toward ethnic Mexicans slowly changed. Ethnic Mexican soldiers had become “brothers in arms” during the war as they fought in Anglo units, not segregated as African American soldiers had been. (See Civil Rights section for court cases and the ending of California school segregation.)

-

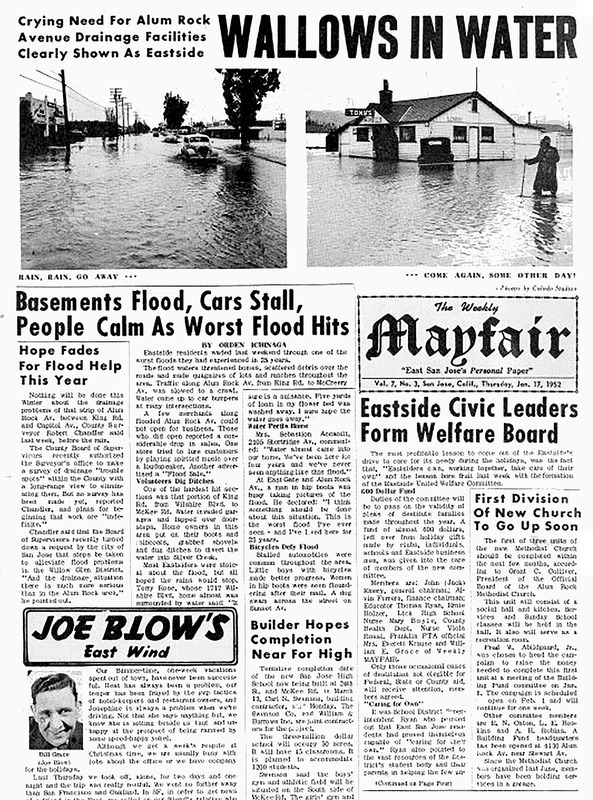

Eastside San JoséThe area known as the Eastside San José was first settled by Puerto Ricans, who left low-paying Hawaiian canefield jobs during WWI for higher paid agricultural work in Santa Clara County. Prior to WWII, concerned that Mexicans might move into their neighborhoods, Santa Clara County civic leaders imposed racial/ethnic restrictive covenants and endorsed redlining policies towards Mexicans. This would concentrate the Mexican populations into the Downtown Colonia or the unincorporated Eastside. Mexican migrants and exiles from the Almaden Mine joined the Eastside Puerto Rican settlement in the early 1920s. These mineworkers wanted to be near other Spanish speakers as well as cannery and farm jobs. In 1931 the Mayfair Packing Company, for which the Mayfair District is named, was built on the Eastside and became one of eleven canneries and packing plants in San José. During WWII, ethnic whites left for higher paying munitions industry work and Mexican workers filled cannery jobs and settled there in large numbers. In 1955 the Mayfair District, nicknamed "Sal Sí Puedes" (Get Out If You Can-a name taken from an original Mexican landgrant), was home to 4,500 residents, of whom 3,000 were of Mexican descent. The segregated Eastside provided empty lots for group camping, mobile rail housing, or long-term housing in apartments, boarding houses, and rental units. Families would often pool their money to purchase an unimproved lot where they could build their own homes. In this way, worker neighborhoods were created with a variety of owner-built housing. For decades the segregated Eastside area remained unimproved with no paved streets or street lights.

-

The San José Mexican Downtown Colonia Before and After WWIIAs more seasonal Mexican immigrant workers arrived in the Valley, civic leaders worried that a year-round Mexican settlement would lower Anglo property values. Between 1920 and 1945, racially/ethnically restrictive covenants (land deed restrictions) and racial/ethnic redlining (lender refusal to offer loans in certain areas) on housing in cities and towns were enacted. These reinforced the segregation of Mexican colonias like San José’s old Pueblo neighborhood, located next to the less desirable industrial area filled with canneries, packing houses and railroads. As more seasonal Mexican immigrant workers arrived in the Valley, civic leaders worried that a In 1900, Mexican and ethnically white Portuguese, Spanish and Italians resided in the Downtown Colonia. When the number of Italians moving to the old Pueblo, between the 1880s to the 1920s, expanded beyond the housing capacity, they moved into the northern, western and southern adjacent neighborhood. The southern neighborhood became known as “Goosetown”. Throughout California, Mexican colonias were pejoratively called "Mexicantowns" or "Jimtowns" (thus racially equating Mexicans to southern African Americans, who were subjected to Jim Crow laws). Historian Suzanne Guerra notes, in the 1920s, the old Pueblo, referred to by Anglo Americans as “Mexicantown”, was hemmed in by urban development and adjacent orchards resulting in fewer places to live in San José. Historian Gregorio Mora-Torres observes that by WWII, the Italian residents of the Downtown Colonia and “Goosetown” moved to other neighborhoods throughout the city. WWII also enabled ethnic Mexicans to move up to higher paying, more stable jobs in the unionized canneries, so they bought the vacated Italian homes in the Downtown Colonia. During the 1940s, the Downtown Colonia expanded north to St. Augustine, south to San Carlos Street, and west beyond the Guadalupe River. By the late 1950s, it had reached all the way to Home/Virginia Streets. Mexicans also lived in the community north of Santa Clara Street and between Second Street and the Coyote River. This spurred the development of Mexican owned businesses downtown to serve Spanish speaking residents in the region.

![Women Strikers at CalPak Plant #9 [California Packing Corporation Pickle Plant. became Del Monte, located at Jackson and N. Seventh Streets, San José]](https://exhibits.sjsu.edu/files/large/95962c6511a2df52f90cf7999808644b2a7b44a3.jpg)