Topic Three Exhibit

The History of Cannery Development in Santa Clara County

- Title

- The History of Cannery Development in Santa Clara County

- Description

-

Following early experimentation with horticulture, the canning industry was established in 1872. Aided by an expanded railroad system and access to broader markets, Santa Clara County became the capital for fruit processing/canning. In 1920, the county produced 90% of California’s canned fruits and vegetables, a share that continued into the 1950s. Increased mechanization and more efficient processes gradually replaced most of the hand labor in the canneries. The construction of new packing houses and canneries west of the Guadalupe River, north of Jackson, and south of Keyes Street drew migrant ethnic Mexican laborers into those areas of San José.

Early promoters called San José “The Garden City.” To take advantage of bumper crop years, keep their product fresh after the season, and utilize distant markets, orchard ranchers preserved their fruit through canning and drying. In 1871 at his home on The Alameda, Dr. James Dawson, a local doctor/fruit grower, formed Dawson & Company, which In 1875 was renamed the San Jose Fruit Packing Company (SJFPCO), located at the corner of Fifth and Julian Streets. In 1893 the company, relocated to the west side of the Guadalupe River south of Auzerais Street, was the largest cannery in the world. By 1900 canned food production had become the second largest industry in California, with Santa Clara County in the lead. During the 1930s, 38 canneries hiring up to 30,000 people at peak season operated in the county, several run by huge corporations such as Libby’s, Hunt’s, Richmond-Chase, and Calpak.

Commercial sales of fruit increased with the construction of the San Jose Fruit Packing Company facility in 1875. Workers at the first canneries included local residents and seasonal migrants. Some employers offered company housing for skilled workers, though individually rented boarding house rooms and hotel rooms were more typical. Worker neighborhoods with small family homes soon appeared adjacent to packing houses and canneries. San José's Eastside grew after the Mayfair Fruit Packing Company was constructed in 1944, in the largely Mexican neighborhood known as the Mayfair district. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/812986670

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 001

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Formation of Producer Exchanges in Santa Clara County

- Title

- Formation of Producer Exchanges in Santa Clara County

- Description

-

Canners and growers formed producer exchanges or cooperatives in which groups of farmers producing the same type of crop collaborated to negotiate prices, hire labor, and access larger markets. In agriculture, these exchanges were characterized by ”horizontal integration,” in which companies of the same industry band together for harvesting, processing, and selling. Just as in Southern California citrus, Santa Clara County canners and growers formed a producer exchange in 1899. San José Fruit Packing Company (SJFPC) joined with seventeen other companies (including half of the canning establishments in California) to form the California Fruit Canners’ Association (CFCA), which eventually operated 28 fruit and vegetable canneries through the state and acquired operations in four other states. Within four years, CFCA was the world’s leader in fruit and vegetable canning and drying. By 1916 the CFCA had merged with five other canneries to form California Packing Corporation (CalPak), developing into the Del Monte Brand, the first national company in the United States, offering 50 products.

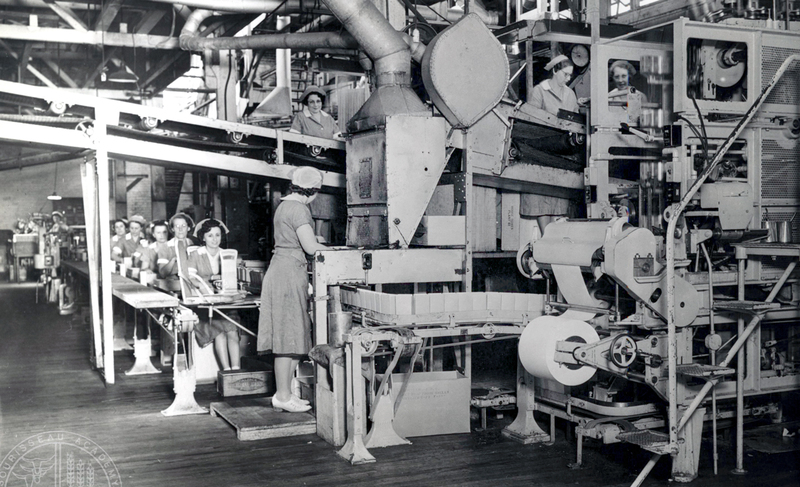

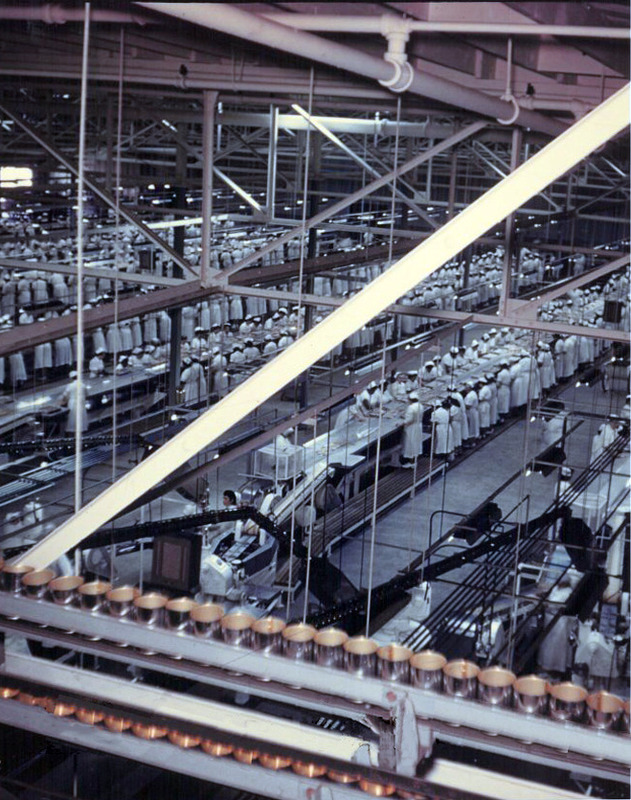

Cannery operations were large facilities, with warehouses, processing facilities, railyards, garages, shops, and offices, employing several hundred to several thousand people. As a regional hub for the food processing industry, local canneries received produce not only from the Bay area but from much of Northern and Central California. Historian Glenna Matthews states that by the 1930s Calpak was the largest canner in California and Santa Clara County had become the fruit processing capital of the world. This photo shows women packing prunes at Calpak Plant No. 51 on Bush Street, south of The Alameda. - Additional Online Information

- Del Monte Packing Plant History

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 002

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Women Dominate the Ethnic White Cannery Labor Force Pre-WWII

- Title

- Women Dominate the Ethnic White Cannery Labor Force Pre-WWII

- Description

-

Canneries are labor-intensive operations, and the labor force required to serve this expanding industry grew with the increase of orchards under production. Jobs were clearly divided along gender, ethnic, and racial lines. Chinese men, Mexican Californio women and men, and Anglo men and women filled the first cannery jobs when the canneries during the 1870s and 1880s. Following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish immigrants soon dominated the Santa Clara County cannery labor force into WWII.

By the 1930s, Santa Clara County’s 38 canneries were the largest employers of women in California. Historian Glenna Matthews divides these canneries into three categories: the large corporate canners of Libby’s, Hunt’s, or Calpak; the smaller joint firms such as Richmond-Chase (2,073 peak season workers); and the marginal single canneries, including Garden City Canning Company (197 peak season workers).

In the 1930s, white ethnic women had risen to supervisory positions as floor ladies, with full authority over subordinates. During WWII, many of these women moved to better paying positions in defense industries and jobs vacated by men. By the mid-1940s, the percentage of women in the American workforce had expanded from 25 to 36 percent. With the wartime labor shortages, more Mexican women were recruited to work in the canneries. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/812986246

- Additional Online Information

- Cannery Life: Del Monte in the Santa Clara Valley - History of San José

- Looking Back: Canning in the Valley of Heart's Delight | San Jose Public Library

- Cannery Tour | Campbell Museum

- Santa Clara Valley Women Cannery Workers

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 003

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Mexicans Move to Cannery Work During and After WWII

- Title

- Mexicans Move to Cannery Work During and After WWII

- Description

-

WWII was a profitable period for growers, packers, canners, and workers as destruction of farmland in Europe and the mobilization of the military worldwide generated a huge demand for canned goods. Over half of Santa Clara County canning production was allocated for the war effort. Meanwhile, canneries in San José suffered labor shortages because of the absence of men to the military and the shift of ethnic white women to higher-paying, year-round “Rosie the Riveter” manufacturing jobs, such as at Hendy Iron Works.

In response, Mexican women and braceros filled cannery jobs. During peak periods, canneries operated non-stop, and many provided transportation during the night shift or allowed women to work until 6:00 a.m., when public buses began to operate.

From 1948 to the 1970s, among cannery women workers, Mexicans comprised the largest ethnic group, with Mexican women working on the line under the supervision of older Italian and Portuguese women, while Mexican men worked in the higher-paying year-round warehouse jobs. Second-generation, English-speaking Mexican American women moved easily from the cannery line to higher- paying supervisory positions and front-office jobs. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/812986764

- Additional Online Information

- Del Monte Plant #3 Overview (1999)

- "Rainbow Harvest" - Dole Fruit Cocktail

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 005

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Seasonal Work and the Shape-Up

- Title

- Seasonal Work and the Shape-Up

- Description

-

Fruit and vegetable harvests are seasonal and must be processed immediately to ensure peak quality. Large canneries with access to produce from other regions might shift from one product to another, operating year-round. During harvest season, canneries operated around the clock, with three shifts of workers per day. While some workers returned annually, new employees were hired seasonally through “shape-ups,” an informal selection process in which workers gathered in front of the office hoping to be hired at the cannery. Due to the large number of canneries and packing houses in the county, workers usually had several opportunities to find work nearby. During labor shortages, canneries in Santa Clara County advertised in Bay Area newspapers to ensure at least a minimum number of applicants.

Having a connection in the cannery workforce–friends or family–often resulted in a hiring preference, and these ties were also helpful on the job as experienced workers provided support and instruction to newcomers. Because employment was seasonal, workers maximized income while jobs were available, working daily and often overtime. This might mean hiding a pregnancy (because pregnant women were not hired), working when sick, or staying on the job even after an injury. Workers wanted to make sure that they would be asked to return for the next season. - Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 007

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

- Media

Eastside Plant

Eastside Plant

Gender Division in Cannery Work

- Title

- Gender Division in Cannery Work

- Description

-

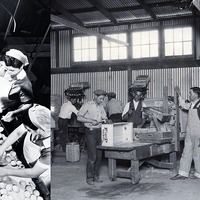

In the canneries up until the 1970s with the implementation of the 1960s Civil Rights legislation, men held year-round jobs in shipping and warehouses, with women assigned to “semi-skilled” seasonal assembly-line hand labor–peeling, cutting, and slicing–standing at work stations all day except for lunch and breaks. Most women were assigned to processing operations or “women’s department.” The monotony and boredom of assembly-line work was a strain, unlike men’s jobs, which allowed for more independence. Cook-room, labeling, stacking, and boxing machines were generally operated by men, who also managed the storage and shipping warehouses. Under the assumption that they were better suited for physical labor and were supporting families, men were assigned to the higher-paying work of supervising, heavy lifting, and equipment operation and maintenance. Full-time jobs provided higher wages and opportunities for advancement, along with a degree of autonomy.

Due to these gendered job categories, women also suffered from limited opportunities for advancement. Not until the 1970s, after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, would they move into higher-paying, year-round jobs traditionally reserved for men. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/812986452

- Additional Online Information

- Women's Work and Chicano Families: Cannery Workers of the Santa Clara Valley on JSTOR

- Women's Work and Chicano Families

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 009

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

- Media

Assembling Fruit Crates

Assembling Fruit Crates

Ethnic and Immigrant Division in Cannery Work

- Title

- Ethnic and Immigrant Division in Cannery Work

- Description

-

Not until the 1940s were Mexican women born in the United States, fluent in English, finally able to advance to office work or supervisorial jobs. Prior to that time, line supervisors were typically Italian or Portuguese, while crews were overwhelmingly Mexican. Supervisors held a degree of authority and could dismiss workers at will. Forewomen circulated the shop floor, enforcing rules, instructing workers, and pushing for faster, more accurate work. Most importantly, forewomen had complete discretion in assigning workers.

While ethnic white women might do the same jobs as Mexican women, they were often segregated by their supervisors, who sometimes helped members of their own group secure better jobs. Combined with the language barrier, Mexican women found little basis for solidarity with these co-workers and sometimes perceived comments from supervisors as racially biased. In addition, although they all might speak Spanish, relations between American-born Mexicans and Mexican immigrants could sometimes be strained. - Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 011

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

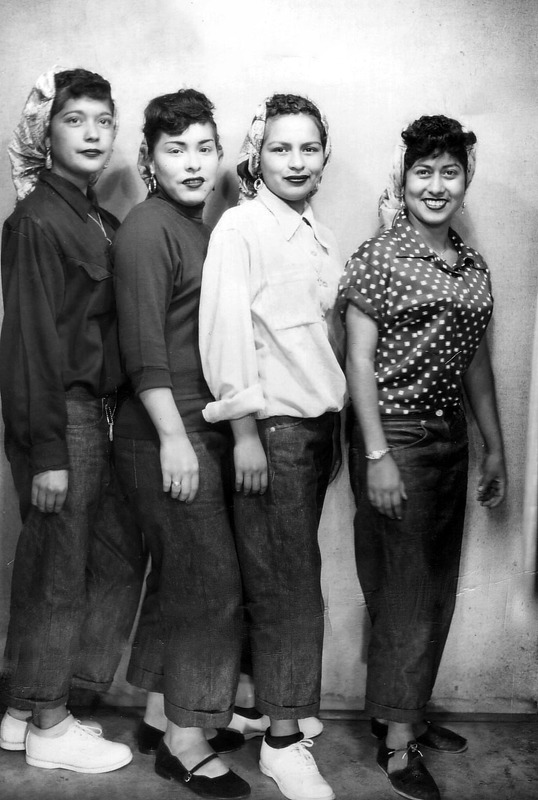

Women's Work Culture

- Title

- Women's Work Culture

- Description

-

Many women found jobs in the canneries through other family members who worked at the same plant. Since little job training was provided, family members could offer advice on the use of equipment as well as how to work with supervisors. Lunching together, sharing babysitting, or traveling to work with family members strengthened kinship networks, and new friendships developed with people they may not have met outside the cannery. Unlike the men who worked in shipping, warehousing, or as equipment operators, before 1970, women did not view cannery jobs as a permanent occupation because there were few opportunities for training and advancement.

Women workers, no matter their background, shared mutual concerns about wages, working conditions, and poor supervisors. There was no time to socialize while on the assembly line or during brief breaks, and the noise made it hard to converse. In the 1930s, shared concerns over workplace safety and low wages led some Mexican women to become involved in union organizing efforts, including strikes, and to rely on social networks for support. “Women’s cannery work culture” made the daily routine easier because women shared their experiences, helping each other adjust to the challenges of the workplace. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/812986385

- Additional Online Information

- Women's Work and Chicano Families: Cannery Workers of the Santa Clara Valley on JSTOR

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 013

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

- Media

Cannery Women Posing

Cannery Women Posing

A Day on the Cannery Assembly Line

- Title

- A Day on the Cannery Assembly Line

- Description

-

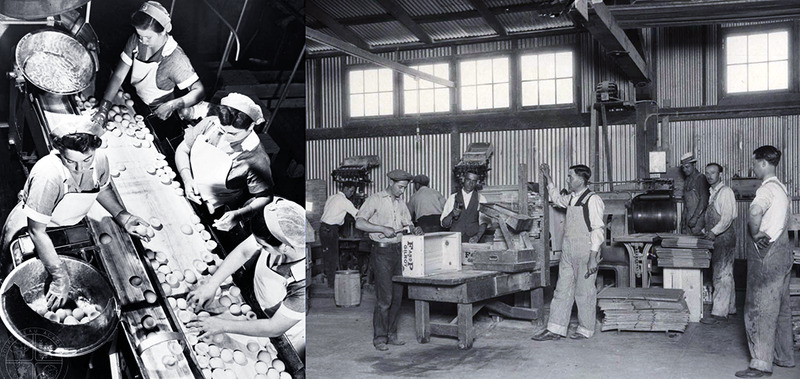

By the 1950s, many operations formerly done by hand were now at least partially performed by machines. Fruit arriving at the cannery, such as peaches, was dumped onto “shakers”; then onto the conveyor belt for cleaning, washing, pitting, and halving by machine; and finally sorted into grades by hand. A few women supervisors oversaw this female-dominated task.

On the floor, workers stood at their stations sorting fruit as it came down the conveyor. Cans on conveyors filed by the seam-inspectors, and women “checkers” sealed the cans before they were loaded into cookers. Women concentrated on doing their jobs quickly in order to meet required quotas. Processing areas were noisy, with the constant clamor of machinery and cans running along conveyor belts. Chemicals such as lye and chlorine were used to wash and clean the fruit. Some women who worked in steaming and canning spinach complained of their nails falling off due to prolonged submersion into the spinach vats. Fruit and vegetable processing required a great deal of handwork to sort, weigh, and fill cans with sometimes steaming hot produce. Once canned, some women looked for dented cans before they were boxed up. The work was demanding and exhausting, constantly proceeding at a pace set by the conveyor belt. When the women got home, their bodies smelled like the fruit or vegetable in which they worked all day, particularly tomatoes. It was difficult to get adequate rest. Many women cannery workers complained about hearing the clanking of the machines even in their sleep.

By the 1940s, shifts usually lasted eight hours but could be longer during peak harvest periods, when some canneries operated on a 24-hour schedule. Companies facing labor shortages encouraged regular employees to work overtime, and despite the demands of the job, many welcomed the opportunity to earn extra money. - Scholar Talk

- https://vimeo.com/812986320

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 015

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Cannery Injuries and Hazards

- Title

- Cannery Injuries and Hazards

- Description

-

Before the 1930s, workdays for women cannery workers could be up to 18 hours, or 96 hours a week. Historian Glenna Matthews notes that in 1913 the Industrial Welfare Commission was formed to protect laboring women and children but excluded workers in “perishable materials” such as cannery workers.

A high percentage of women working in canneries at that time were immigrants who spoke limited English, so receiving adequate training was difficult, and safety instructions were printed only in English. Assembly-line labor was repetitive, and women stood at their stations for hours working with their hands in acidic fruit. Many women reported severe damage to their hands and fingers from operating swiftly-running machinery. Many reported severe damage to their hands, not from traumatic injuries but from nicks and cuts received while cutting fruit by hand. As cans rattled along conveyors in buildings that were sometimes the size of four football fields, noise was also a constant problem. Industrial chemicals were hard on the skin and a hazard to eyes and lungs. At the peak of the season, workers might put in ten hours a day, six days a week, leaving them exhausted and dehydrated at the end of their shift.

Women continued to bring health and safety concerns to management and their unions. During and after WWII, some larger canneries, such as Del Monte, created an infirmary with a nurse near the processing line. While conditions generally improved over time, anthropologist Patricia Zavella, in her book Women’s Work and Chicano Families, noted that in 1978, canneries were still considered one of the most dangerous industries, second only to lumber manufacturing according to the U.S. Department of Labor. - Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 017

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Women's Double Work Day

- Title

- Women's Double Work Day

- Description

-

Cannery women were also faced with the double work day, often working full time or overtime at the cannery while still expected to care for the home and family. Still, most considered cannery work a better alternative than field or orchard jobs. Working seasonally enabled them to supplement the family income or serve as the breadwinner when husbands were unemployed, while maintaining their primary roles as wives and mothers.

A major challenge for cannery women was finding appropriate and affordable childcare. During the 1940s and 1950s, CalPak operated a nursery at the Del Monte Plant #3, providing childcare during the day and second shift. However, as childcare was unavailable at most canneries, mothers left their children with family members or neighbors, while others paid for babysitters or bartered for care with co-workers. Husbands and wives who worked at the same plant might arrange complicated shift schedules.

Working mothers believed that, in easing their husbands’ responsibility as providers, they could ask for more assistance with housework. However, men often found it difficult to participate in many of these domestic chores, so cooking and childcare were often handled by older children.

Women cannery workers knew that their paychecks enabled them to provide more assistance to their children, send their kids to college, allow their husbands to attend trade school, start their own business, or have a higher standard of living, and they wanted a say in how household money would be spent. Women made time to do the necessary household chores by extending their day, staying up late or waking early. - Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 019

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley

Cannery Decline

- Title

- Cannery Decline

- Description

-

At the height of the fruit season during WWII, canneries operated seven days a week with shifts as long as eleven or twelve hours per day. After World War II, demand for canned fruit rapidly declined, leaving owners holding large loans that had been taken out to expand productivity. Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, orchards and fields were being replaced by business and research parks and housing developments, creating the emerging Silicon Valley. Changes occurred also when the Teamsters Union took cannery representation away from the AFL, and when Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (1967) required that jobs could not be classified as “male” or “female” work. By 1976, because most cannery jobs were unionized, women were receiving wage, medical, holiday, and retirement benefits. Although their benefits were still lower than men’s, women found cannery work offered stability, allowing many to become homeowners.

When fruit processing operations began to decline in the 1970s, the growth of manufacturing in the electronics industry and new housing tracts provided opportunities for displaced workers in construction, railroads, warehouse, and assembly work. Unfortunately, these new jobs were not comparable to the higher-wage union jobs in the canning industry. For many workers, the cannery closures meant the end of secure jobs with benefits and the long-term working relationships they had created. By 1987, only eight canneries existed in the valley, the era ended when, in 1999, Del Monte closed its largest cannery, Plant #3, the site of the 1893 San Jose Fruit Packing Company. - Additional Online Information

- Del Monte Cannery Last Day

- Identifier

- B4SV Exhibit Topic Three: Slide 021

- Item sets

- Before Silicon Valley