-

Title

-

Mexican Farm Worker Unionization, 1930-1960

-

Description

-

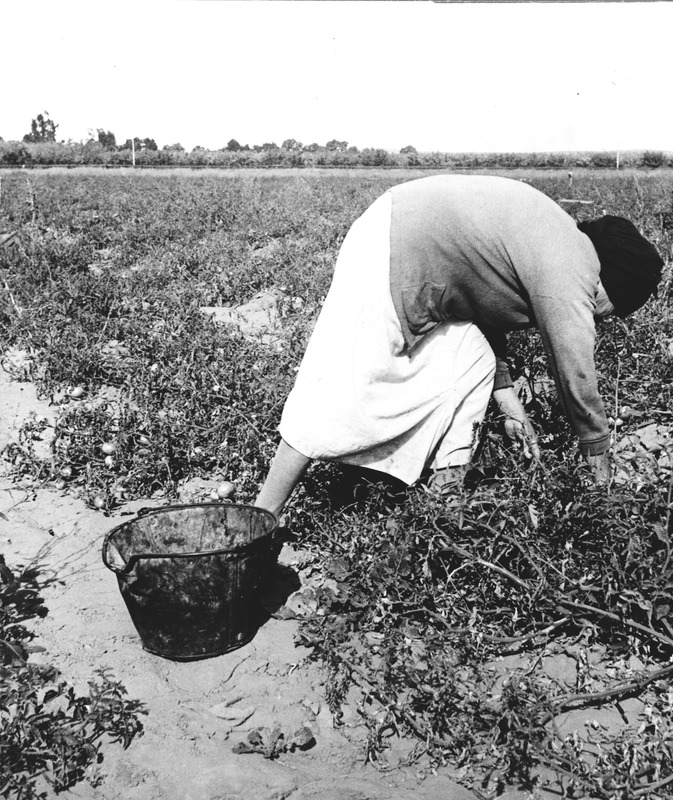

During the Great Depression, ethnic Mexicans viewed labor organizing campaigns as part of the promise of equality and civil rights. During this time, Santa Clara County saw some of the most significant agricultural strikes in the U.S., many involving Mexican workers. Before WWII, most Mexicans worked on farms in the fruit and nut orchards or tomato and pea field/row crops. The Depression of the 1930s saw a deterioration in working conditions and a dramatic decrease in pay for orchard and field workers, who were paid by piece work rather than hourly wages. Historian Glenna Matthews claims that weekly pay dropped from $16.33 in 1929 to $8.04 in 1933. Growers stopped working cooperatively in the fruit exchange and began selling their crops individually, competing with each other and lowering wages even further. During the New Deal, between 1933 to 1937, the federal government supported farmers by buying their crops, thus propping up prices.

In 1931 the new Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU) set up its state headquarters in San José at 81 Post Street, charging monthly dues of twenty-five cents for the employed and five cents for the unemployed. Dorothy Ray Healey, Elizabeth Nicholas, Pat Chambers, and Caroline Decker were among the CAWIU organizers working in the county. The CAWIU undertook thirty-seven agricultural strikes in California. Historian Glenna Matthews contends that Santa Clara County, as in the rest of the nation, saw more strikes and violence in 1933 than ever before, with three agricultural strikes and one brutal non-agricultural-related lynching.

In April of 1933, 2,000-3,000 pea pickers, composed of Mexicans and Dust Bowl migrants working near the Milpitas/De Coto County line, struck for higher wages and lost. In June 1,000 cherry pickers, mostly Spanish workers from the Mountain View area, struck for higher wages. That same year, the cherry picker strike was considered the most violent of the three strikes in Santa Clara County. Workers were successful and won a 50-percent raise, from twenty cents to thirty cents an hour. According to the La Follette Civil Liberties Committee Report (1936-1941), the cherry pickers were successful because the Spanish workers were homeowners and had invested in their communities, unlike the migrant Mexican and Dust Bowl pea pickers.

In August 1933 pear pickers staged a strike, CAWIU’s most successful strike in the County, largely due to organizer Caroline Decker, who gained the support of the Palo Alto Democratic Club. In turn the Democratic Club, state and federal government officials, and the California Bureau of Labor Statistics backed the union’s right to picket, opposing the growers who had obtained an injunction against picketing workers.

The Bracero Program made it difficult to organize farmworkers throughout the Southwest, as well as Santa Clara County, because braceros were used as strikebreakers until the program ended in 1964. Ernesto Galarza organized agricultural strikes (though not in Santa Clara County) using the National Farm Labor Union during the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1937, workers in thirteen dried fruit companies decided to unionize. They organized the Field Practice Group and initially contracted with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), considered a “company union” less concerned with non-white members, who represented 98% of the dried fruit workers of Santa Clara County. Unlike cannery workers, in 1941 dried fruit workers left the AFL and voted for representation from the more left-wing CIO, which promoted for the largely Mexican workforce higher wages, retirement benefits, and a hiring hall instead of a shape up.

-

Scholar Talk

-

https://vimeo.com/812976025?share=copy

-

https://vimeo.com/812975521?share=copy

-

Identifier

-

B4SV Exhibit Topic Five: Slide 001