-

Title

-

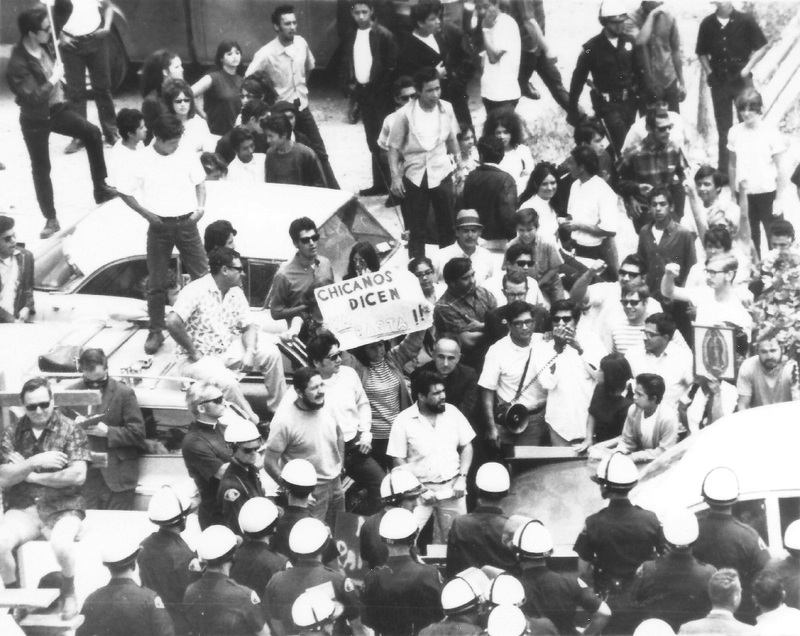

The Rise of Chicano Politics in the 1960s and 1970s

-

Description

-

U.S policy long encouraged immigrant assimilation, with new citizens expected to acquire English as their language and culture in order to become “American.” In the United States, the term “Mexican” is a large category that encompasses American-born people of Mexican descent, immigrants from Mexico who have become naturalized citizens and Mexican nationals who reside in the United States but are not American citizens.

While some immigrants chose not to become citizens, reasoning that it might not make a difference in how they were treated, some ethnic Mexican organizations supported naturalization. The first Mexican American organizations, during the pre-1960s period, advocated for citizenship and assimilation. During the 1960s and 1970s, a number of Mexican Americans questioned whether assimilation was possible or even desirable because of prevalent racism in the United States.

Equity in education remained a major issue, an obstacle to better jobs and a better life. A new generation of ethnic Mexican college students uncovered their history and critically analyzed what they had been taught in public schools. At the same time, with the rise and successes of César Chávez, a sense of ethnic consciousness and unity grew around the farm labor movement. The Black Civil Rights Movement had also inspired many ethnic Mexicans to consider whether more direct strategies, moving from the courts to the streets, would be more effective in obtaining their legal rights under the U.S. Constitution.

Although ethnic Mexicans suffered the same types of economic, social, and political discrimination that African Americans and other people of color endured, there are important differences. American policies on immigration and citizenship affected all Mexicans. American-born Mexicans who had been deported during the Depression were suspected of taking jobs that could be offered to citizens. Ethnic Mexican families made up of both citizens and undocumented immigrants faced the possibility of losing one or both parents to deportation. Mexican immigrants tended to live in neighborhoods with other native language speakers in order to survive with their limited English. Since bilingualism was not generally viewed as an asset, speaking Spanish could be an obstacle.

Some Chicanos viewed themselves as a colonized people, based on their belief that the United States government had failed to live up to the promise of full citizenship under the 1848 treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which had ended the war between the United States and Mexico. Mexican Americans were not accepted as fully American, but neither were they truly Mexican. Their closest identity was with Aztlán, the legendary original homeland in the Aztec migration stories, identified as the area of the Southwest conquered during the Mexican American War. In this case, the terms Chicano and Chicana began to be viewed as a positive identity to express self-determination and political solidarity.

-

Identifier

-

B4SV Exhibit Topic Six: Slide 002