-

Title

-

Mexican Criminalization

-

Description

-

By the early 1860s, Californios faced deteriorating economic, social, and political status, suffering “a second conquest” by the Americans. As historian Stephen Pitti notes, Anglo Americans racialized their views of Californios seeing the entire Mexican population as oversexed, criminal degenerates. Mexicans became the victims of racial violence as self-appointed Anglo vigilantes shot or hung any Mexicans they considered criminals.

Mexican Californios were called “greasers," a term originating from the Mexicans engaged in the hide and tallow trade who, while processing beef fat, became covered with grease. In 1855 the California Greaser Act was passed, an anti-vagrancy law targeting all ethnic Mexicans. Further, the California Act of 1855 ended the State Constitutional requirement that laws be translated into both Spanish and English. These laws institutionalized racism in Santa Clara County, encouraging harsher punishments for non-white residents. Historian Stephen PItti points out that between 1850-1864 “all but one of the accused criminals hung in the county were ethnic Mexicans.” Mexicans could not sit on a county grand jury until the 20th century, and between statehood in 1850 to 1900 Mexicans could not become a sheriff or police officer.

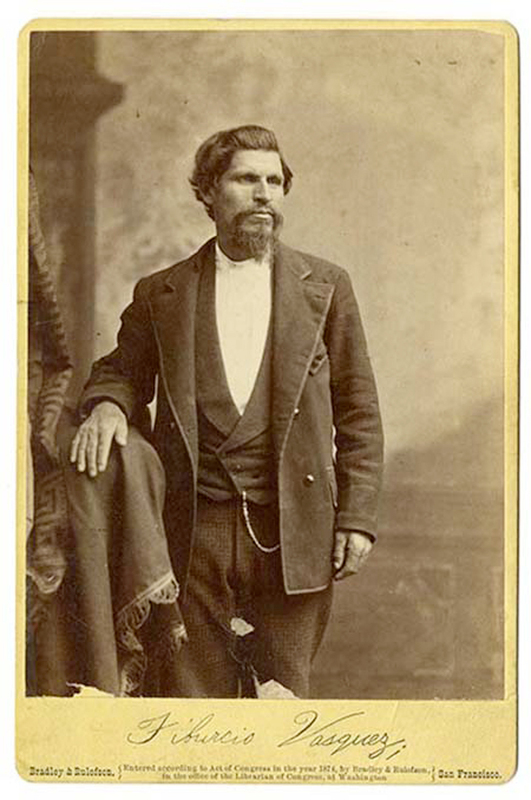

Without legal protection and with limited access to land or jobs, during the 1860s and 1870s a few Californios became bandits or highwaymen to avenge the harassment and racial discrimination Mexicans residents endured. Joaquín Murieta is the most famous of the “social bandits.” Tiburcio Vásquez, grandson of the first mayor of San José and an educated, bilingual member of an upper class Californio family, was another. Some Californios considered Vásquez a “Robin Hood,” fighting against Anglo atrocities and upholding Mexican civil rights. Anglo Americans considered him an outlaw. Accused of crimes committed from 1854 to 1874, he was tried and convicted for one murder and executed by hanging in 1875 in the jail yard behind Santa Clara County Court House across from St. James Park. While he admitted that he was an outlaw, Vásquez came to symbolize resistance due to legitimate grievances against Anglo American domination and Mexican lynchings that had become all too common.

-

Scholar Talk

-

https://vimeo.com/811441940/ffee9b6d70?share=copy

-

https://vimeo.com/811441845/09fa2c7102?share=copy

-

https://vimeo.com/811441775/d48ed757da?share=copy

-

https://vimeo.com/811441701/cd2acca19b?share=copy

-

Identifier

-

B4SV Exhibit Topic One: Slide 015

Tiburcio Vasquez

Tiburcio Vasquez