Items

-

The California Lowriders: A Merging of Chicano Civil Rights and CultureCruising originally began in downtown San José until police diverted riders into the unincorporated Eastside, particularly near the intersection of Story and King Roads. According to Jesus Flores, a car club historian, low-riding crowds grew on the Eastside. Similarly, in Los Angeles low-riders had been pushed off of Whittier Boulevard by new restrictions. Many ethnic Mexican Angelenos faced similar obstacles to those in Santa Clara County. Lowriders cruised up to Eastside San José in numbers that resulted in the creation of “No Cruising” zones. Low riding culture went underground until the City of San José lifted the City’s low-riding restriction in 2022. According to Smithsonian curator Steve Velasquez, during the Chicano Movement in the 1960s and 1970s, car clubs took on a politically empowered perspective, inviting family involvement and undertaking community events such as fundraising for the United Farm Workers labor union and hosting health initiatives. The car-culture aspect of low-riding was 10 percent, while the social aspect was 90 percent. Mexican veterans had utilized mechanical skills learned in the military to modify older models and lowered the rears of the cars with weights in order to stylishly cruise the roads. So it was no surprise when San José introduced the use of hydraulics in the low-riding scene. In 1977, San José State University students Larry Gonzalez, Sonny Madrid, and David Nunez pooled their money and published the first Low Rider Magazine in a small store front on Willow Street in San José. Just as the Chicano Movement utilized mythical Aztec artistic designs reminiscent of Diego Rivera murals, so did low-rider car artists. Velasquez noted that car artistic expression became a tool of resistance, calling the cars “mobile canvases.” As noted in Smithsonian Magazine, low-riding became “the nexus between art and activism.

-

The California Chicano Cultural Movement: The Chicano Music and Literary MovementsThe Chicano Music Movement San José-based Flor del Pueblo was one of the most influential musical ensembles of the Chicana/o Movement, and inspired activism for social justice with local roots and an international perspective. Formed in the 1970s, they performed with various South Bay Teatro Chicano groups — including El Teatro Campesino — and were on stage at the Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 1970, when police violence broke up a peaceful demonstration. Their 1977 album, Música de Nuestra América, incorporated Latin American protest music influences on Chicana/o Movement musical style. Chicano Literary Movement The Chicano community was rediscovering the power of literature to communicate philosophies and experiences and inspire change. The poem “I am Joaquin,” written in 1967 by Chicano Nationalist leader Corky Gonzalez, was significant as an anthem for the Chicano Civil Rights Movement and was soon adapted into a short film directed by Luís Váldez. The poem reflects on the complicated relationship of Chicanos to America, with a heritage that incorporates Spanish, Aztec, American Indian, and European American sources. While fighting for integrated schools and equal access to education, the Chicano Civil Rights Movement strongly supported bilingual education, which was illegal in many states at the time. A long history of colonization had created a rich oral tradition of storytelling, plays, and narrative songs called corridos. Indigenous oral traditions provided a way to express discontent with racial discrimination and envision an alternative future. A powerful voice among Chicana writers is poet and publisher Lorna Dee Cervantes. Born in San Francisco and raised in downtown San José, she started writing poetry as a teenager and was determined that her words would be accessible to readers like herself. In 1976, Cervantes founded MANGO Publications, the first to publish many famous Chicano writers, including Sandra Cisneros, Jimmy Santiago Baca, and Alberto Rios. Numerous Chicano newspapers, activist organization newsletters, and scholarly and arts publications arose during this period. These included papers such as El Manchete, Bronce and La Palabra, and Que Tal, a student newspaper. While some were short lived, they documented the concerns of diverse ethnic Mexican communities and interpreted the goals of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement for their audiences. The Chicano Press Association, established in 1969, had twenty two members at its height, mostly in California. Quinto Sol of Berkeley, the first fully independent publishing house, was founded in 1967 at UC Berkeley by Octavio I. Romano. They published the interdisciplinary El Grito: A Journal of Contemporary Mexican-American Thought, the first national academic and literary journal ever published in the United States.

-

The California Chicano Cultural Movement: The Chicano Arts and Mural MovementsChicano Arts Movement Oakland would emerge as the birthplace of Chicano art groups during the Chicano movement. In 1969 the Mexican American Liberation Art Front (MALAF), a Chicano artists’ collective in the Fruitvale District of Oakland, was one of the first Chicano art collectives in the United States. Founded by Chicano artists Malaquias Montoya, Manuel Hernandez, Rene Yanez, and art professor Esteban Villa, it was one of the main poster producers for various protest events and movements in the 1960s and soon created a circle of artists and activists interested in political and cultural work. In I970 the Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) was founded as the Rebel Chicano Arts Front at Sacramento State. This was an artist’s collective run by Jose Montoya, Esteban Villa, and Richard Favela to support the arts in the Chicano community and to educate young people in arts, history, and culture. Their mission also included promoting political awareness, and support for César Chávez and the United Farm Workers. In 1972, the RCAF created the Centro De Artistas Chicanos, a hub for community programs including La Nueva Raza Bookstore and Galeria Posada, RCAF Danzantes, RCAF Graphics and Design Center, and the Barrio Art Program for children. Many of the artists involved were educators, writers, poets, and musicians who contributed Chicano civil rights activism and to the promotion of Chicano art history, literature, and culture. As artists and activists, the silkscreen posters they created were highly political, expressing community concerns and viewed as instruments of social change. The Chicano Mural Movement The Chicano Mural Movement began in the 1960s when murals appeared extensively in the Southwest as part of the national Chicano Movement. While famous Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera had created monumental public art, Chicano muralists used their work to increase the visibility of the Mexican American experience and to advance the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. Murals were painted on buildings, schools, churches, and other public areas in Mexican American barrios, or neighborhoods. Murals continued in their traditional role as a visual narrative, while recording significant social and political events. Traditional cultural icons and symbols were infused with new meaning when they depicted contemporary struggles. In the 1960s and 1970s, many artists were Vietnam veterans and their murals incorporated images of war and loss, along with Mexican revolutionary figures, the struggles of immigrants, and social justice issues relevant to Mexican and Latino-Americans. Although women artists were still in the minority as muralists, the Mujeres Muralistas (MM) in San Francisco was an all-women art collective founded in the 1970s by Patricia Rodriguez, Graciela Carillo, Consuela Mendez, and Irene Perez. Their intention was to celebrate the culture and contributions of Mexican American and Latina women and to recognize the talent of Latina artists. Their images celebrated Latina women artists and historical figures as well as everyday women in the community in their various roles as wives, mothers, and workers. Some in the Mexican community questioned their ability to handle the physically strenuous work, while others questioned their focus on the lives of women and images of beauty. Public acceptance of their art influenced a shift from the stark images of war and loss typically produced by male muralists to a broader range of themes and color palettes. The Women’s Movement had often overlooked the perspectives of non-Anglo American women, and The Mujeres Muralistas’ art recognized Latina women’s experiences as integral to representations of Mexican American culture and socio-political issues.

-

The California Chicano Cultural Movement: Chicano Theater MovementContinued from 18

-

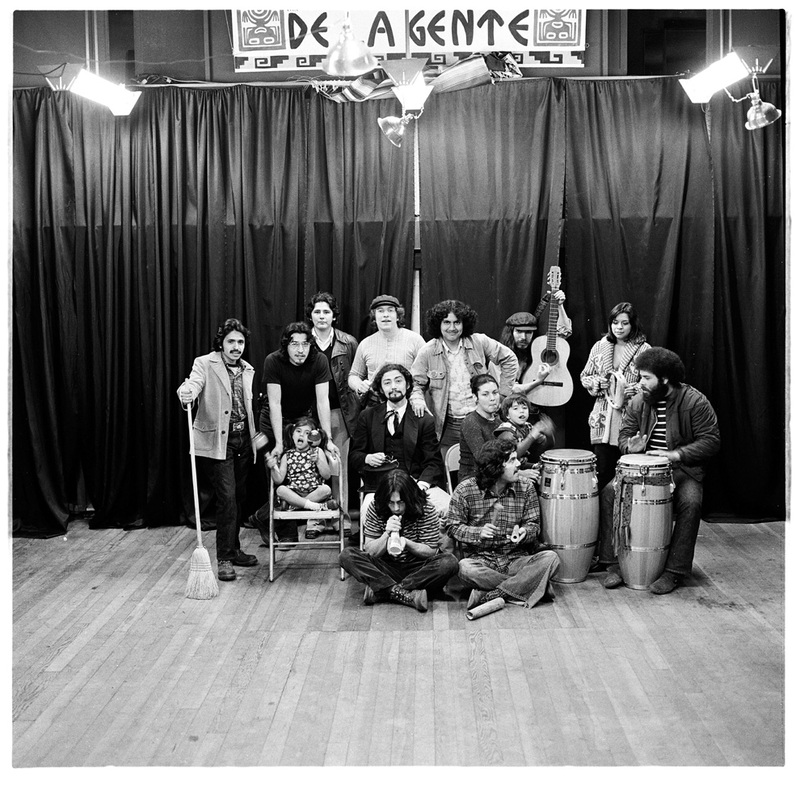

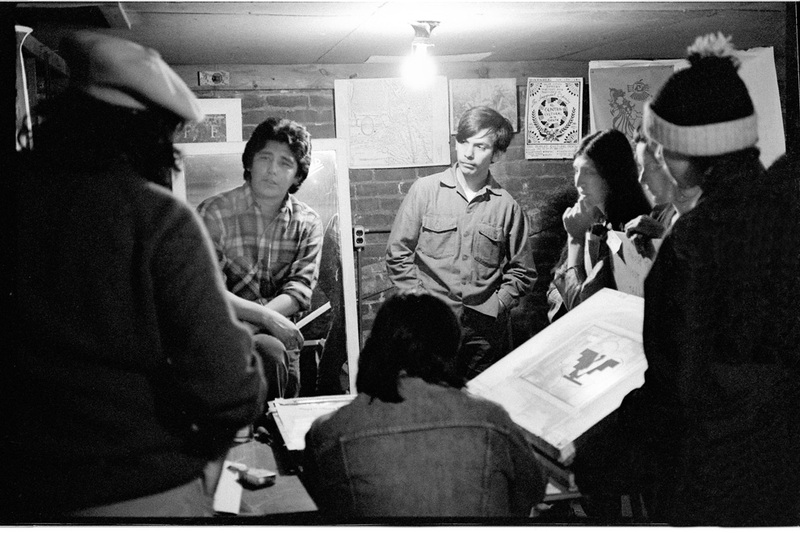

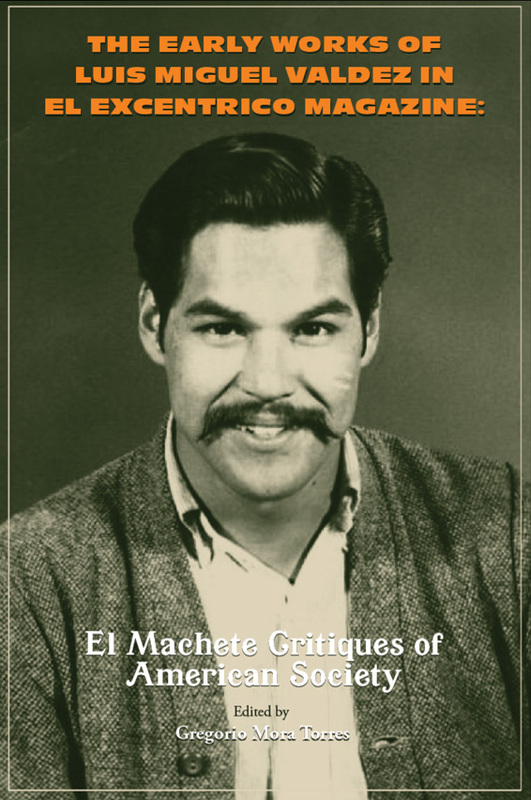

The California Chicano Cultural Movement: Chicano Theater MovementEl Teatro Campesino El Teatro Campesino (The Farmworkers’ Theater), one of the most influential elements of the Chicano Arts Movement, has its roots in San José. San José State College students Luís Váldez and Roberto Rubalcava joined the Marxist Progressive Labor Party (PLP) and traveled to Cuba in 1964 as part of a PLP delegation. Váldez joined the anti-establishment radical theater group the San Francisco Mime Troupe upon graduation. He was introduced to guerilla theater and Italian Commedia dell'arte, forms which would influence the development of the Chicano Teatro and the one act play “acto.” In 1965, Váldez joined César Chávez and the United Farmworkers Union in drafting the El Plan de Delano, which proclaimed the principle of a movement for social justice. Váldez brought together farm workers and students to form El Teatro Campesino in 1965 and toured union halls, the fields, and migrant camps. This idea of performing events of the day back to the workers was similar to the Living Newspaper of the WPA during the 1930s. El Teatro aimed to educate and inform the farm workers and the general public with social and political commentary intertwined with humor. Their performances took the form of a one act play — “acto” — incorporating myth and history to document farm workers’ lives and aspirations. The “actos” dramatized political and social concerns, while “mitos” (myths) explored myths, legends, and spirituality. Originally based on the experiences of farm workers, their subject matter soon expanded to include other aspects of Chicano culture, history, and social issues. El Teatro set up headquarters in San Juan Bautista, located in San Benito County, just south of Santa Clara County. A few years later, in 1974, Teatro de La Gente was created in the Bay Area as a theater of the people, involving people with no theater background, whether cannery workers, immigrants, or refugees. As one of the few Chicano Theater groups in the Bay Area, Teatro de la Gente performed for political rallies, social rallies, fundraisers, cultural events, and programs at other colleges. Performing in the farm labor camps, they marched with the people, playing music and singing along, then performed on stage. Working with people with little or no theater background but a lot of life experience, they conducted workshops and classes for the community. Teatro de La Gente toured throughout the southwest, performing works that related to the daily experiences of Chicanos. El Teatro strengthened the spirit of people struggling to deal with complex social and economic issues and reinforced the connection with cultural expressions for others. The Teatro Festival, organized in 1973 by Teatro de la Gente, brought Chicano theater groups together from all over the United States, Mexico, and other parts of Latin America. The music that came out of the Farmworkers Movement chronicled the struggle of the farm worker in song and verse. El Teatro also incorporated indigenous music from Mexico and popular music from Latin America. The 1970s soon saw an explosion of Chicano theater on college campuses and in communities throughout the United States, with several annual Chicano theater festivals organized by El Teatro Campesino. El Teatro Nacional de Aztlán (The National Theater of Aztlán) was created by the Teatro Campesino and other Chicano Teatro groups in 1971. El Teatro Urbano was started in 1968 in South El Monte by Rene and Rosemary Rodriguez. Inspired by Teatro Campesino and named by Luís Váldez, this led to the creation of a regional network of Teatro groups in Southern California. El Centro Cultural de la Gente El Centro Cultural de la Gente (Peoples' Cultural Center) was created in 1973 in San José, California. El Centro was a collaboration between El Teatro de la Gente and other San José artists, actors, writers, poets, and visual artists. Teatro and non-Teatro musicians were also developing contemporary Chicano-Latino music. There was an explosion of cultural works produced during that time, including posters, drawings, paintings, musical arrangements, and compositions. Artists of all types shared gallery and theater space and were encouraged to collaborate. The Centro became the center for a multitude of San José Chicano artists presenting everything from visual arts exhibits to city-wide cultural events, and were influential in the development of San José City Arts and Events Programs.

-

The National Chicano Cultural Movement of the 1960s and 1970sDuring the 1960s and 1970s, artists and activists who identified as Chicanos developed a new cultural identity apart from Mexican nationals and the previous generation of Mexican Americans. The mix of cultural influences that were considered inferior to White Americans was a central concept for the Chicano Movement. These beliefs reflected the forging of a unique identity, one that crossed borders and cultures. The 1960s were marked by cultural nationalist struggles in the Third World and an international student movement. The US also reflected this generational change with the emergence of multiple social and political movements, including domestic Black Power, hippie counterculture, and massive mobilization against the war in Vietnam. The national flowering of the Chicano Arts Movement in the US found expression in a variety of mediums, including Theater, Painting/Murals, Music, and Literature. Artists composed slogans of solidarity and envisioned art and culture as crucial aspects of social transformation. Chicano arts would reinforce a positive identity and fortify the community. The Chicano Civil Rights Movement reaffirmed a centuries-long struggle for human and cultural rights

-

Local Community Advocacy: Brown Berets and Black Berets in San JoséIn 1967, David Sanchez dissolved Young Citizens for Community Action to form the Brown Berets (BB), a self-defense group based in East Los Angeles. The BB was known as a militant youth group that protested educational neglect and police brutality, and had strong links to the community and to East LA high school. Together, BB members and students began a series of pickets in front of sheriffs’ offices and police stations. San José’s Brown Berets were organized in the same year and based on the East LA group and Oakland’s Black Panther Party. The Panthers were a Marxist–Leninist and black power political group founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966. San José’s Brown Berets described their mission as protecting the Chicano community from police brutality, promoting equal employment, housing, education, and voting rights, as well as protecting the right to bear arms, and as advocates for bilingual education. They often provided security for protest marches and community events, buffering these groups from potential police harassment. Other organizations took up a black beret and called themselves the Black Berets, in honor of Che Guevara. Their perspective was anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, and internationalist. They created and assisted in many community programs such as food distribution, community patrols, and other activities. While most active in other areas of the Southwest, the Black Berets in San José also made alliances with other groups, and provided security for the Roosevelt Junior High School walkout in 1967.

-

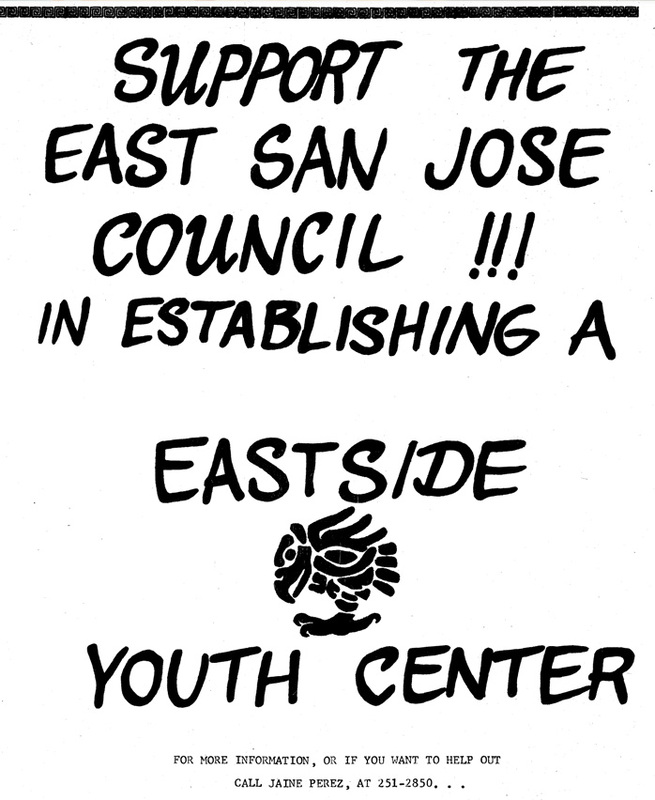

Expanding Community Advocacy in Santa Clara County With CIC, CAP, CPL And UPAThe Mexican American Community Services Agency, Inc. (MACSA) was organized in 1964 by Santa Clara County ethnic Mexican activists to identify ways to respond to the discrimination, racism, poverty, police brutality, educational inequity, and inadequate access to public services that existed in Silicon Valley. Their methods emphasized self-help, coalition building, and neighborhood organizing based on the model established by the Community Services Organization (CSO) of the 1950s. Young people were of particular concern to MACSA because many students were afraid to complain to their parents about the harassment and discriminatory treatment they experienced in schools. Compounding the problem were prevailing attitudes held by many ethnic Mexican parents who saw teachers as authority figures who were not to be questioned. MACSA, however, was broadly successful in focusing its efforts on youth, families, and senior outreach with targeted educational cultural activities and programs. In addition, MACSA developed nutrition programs as well as employment and training programs at youth centers, schools, libraries, and community sites.

-

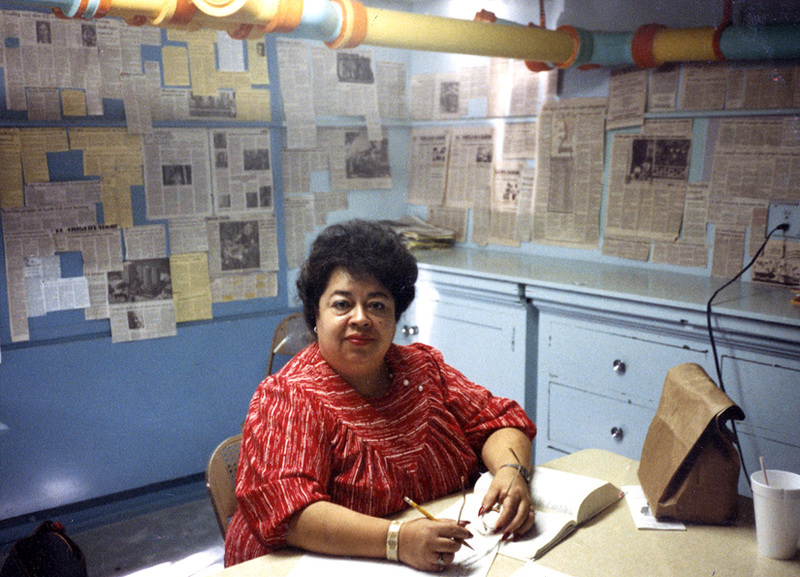

Expanding Community Advocacy in Santa Clara County With CIC, CAP, CPL And UPACommunity Improvement Center (CIC) & Community Alert Patrol (CAP) The creation of the organization Community Alert Patrol (CAP) is a good example of the transition from small community groups focused on single issues to the establishment of formal organizations capable of addressing more complex long-term issues. In 1963 the Community Improvement Center (CIC) began as a self-help program. Sofia Mendoza started working with the CIC in 1963 and was a founding member of Community Alert Patrol (CAP). She remembered, “We just had it. We had reached our limit. The police had guns, mace and billy clubs. They were always ready to attack us. It seemed as if nobody could stop what the police were doing” (Roots of Social Justice Organizing in Silicon Valley). CAP was created to deal with complaints of police harassment and brutality, similar to the Black Panthers in Oakland. Close to a thousand local residents were trained to observe and record police interactions with the public, the most active participants being San José State University students involved in organizing for ethnic studies classes. Community Progress League (CPL) The CIC evolved into the Community Progress League (CPL) by 1965, with Sofia Mendoza leading the campaign to work with parents at Theodore Roosevelt Junior High in the ethnic Mexican Mayfair neighborhood. As discussed in section 6.4, several ethnic Mexican children told their parents that other students and even some teachers had used racial epithets against them. These children had been reluctant to talk and Mendoza encouraged other parents to become involved. Eventually several teachers and the principal were replaced. Despite the new staff, ethnic Mexican parents and some teachers felt other changes were needed in the curriculum and support system for their children. They organized a student blowout/walkout in 1967 at Roosevelt Junior High, which was an inspiration for the LA “Blowouts” (walkouts) and the Chicano Moratorium March the following year. United People Arriba (UPA – United People Upward) The success of the walkout encouraged the group to create United People Arriba (Upward) (UPA) in 1967, which broadened the scope of membership and concerns to include multiple groups and issues. Mendoza and co-organizer Fred Hirsch lead the group. Mendoza recalled, “We wanted an organization that was not limited to one ethnic group, that would organize our entire community, so we called ourselves United People Arriba—United People Upward. We liked the term ‘United People’ because it got the idea across that people from different ethnic backgrounds were coming together in San Jose to work for social change—Blacks, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and whites working together in one organization” (Roots of Social Justice Organizing in Silicon Valley). One hundred thirty people attended their first meeting, many of whom had been involved with the school walkout. They developed a committee system to deal with multiple issues: improving local health services, challenging discriminatory education, expanding welfare rights, monitoring policing tactics, and increasing employment and better housing.

-

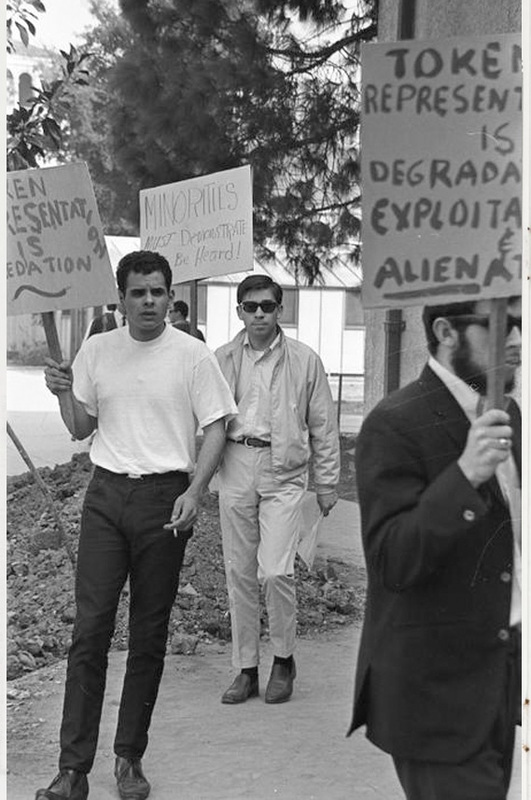

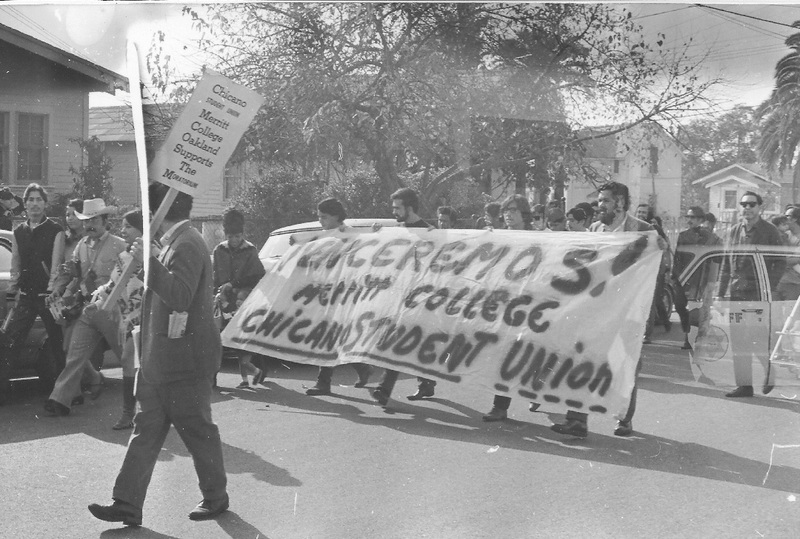

San José Local Groups Fight Discrimination in College EducationAfter WWII and during the 1950s, ethnic Mexican civil rights organizations focused on providing scholarships, reducing high school dropout rates, and promoting college recruitment to help Mexican Americans professionalize, with the aim that educated workers would then give back to their communities. Returning veterans attended college on the GI Bill, and some applied their degrees to education and social services. During the 1960s and 1970s, Mexican American students pursued a new direction, calling themselves “Chicanos” and creating new ethnic Mexican civil rights organizations emphasizing cultural nationalism. Most ethnic Mexicans chose to attend the more affordable community colleges before transferring into four year colleges or universities. San José City College (SJCC) served as such a launching ground. In 1965, Los Amigos, a student organization at San José City College, was founded primarily by young returning veterans to improve educational programs and to keep students in school, working with middle and high school students. Los Amigos programs also dealt with at-risk youth in Juvenile Hall. In 1966, the GI Bill was expanded to include Vietnam War veterans, and many of these older students attended community colleges. At San José City College, students organized tutoring programs and cultural activities and advocated for better educational opportunities. When these students moved on to four-year colleges and universities, they continued their activism. In the 1950s, San José State University (SJSU) was considered a conservative university in its views on race and class. This changed rapidly when ethnic Mexican students of color transferred from the more affordable San José City College to SJSU in the 1960s. The transfer students brought a host of student-led initiatives and activism with them, enabling and leading student demonstrations, walkouts, and picketing. These activities led to the establishment of a counseling center and services for Chicano students prior to the creation of the Equal Opportunity Program (EOP) at SJSU. In 1966, SJSU student Armando Valdez organized Student Initiative (SI), the first Chicano student organization at San José State. SI was dedicated to developing Mexican American student leadership and working with the campus Equal Opportunity Program (EOP). SI began working with local community groups and recruiting high school students to attend recruitment and orientation events at SJSU. Networking with other Chicano student groups statewide, SI transformed into the Mexican American Student Confederation (MASC), advocating for changes in the SJSU curriculum and textbooks, and for the creation of a Mexican American studies program at SJSU. Bilingual education was also a major focus, with Ernesto Galarza serving as a non-faculty advocate. In 1968 SI organized the Chicano Commencement walkout, protesting the low Chicano student enrollment and low numbers of Chicano faculty. This walkout was the first protest by Mexican American students on a college campus in California. In 1968, equity in education was still a major priority for the ethnic Mexican community, and many different student organizations had been started in high schools and colleges to support these students. Often, parents and teachers were deeply involved in these groups. The Mexican American Student Confederation (MASC) at SJSU created summer cultural programs to teach junior high school students Mexican visual art, music, dances, and cooking. They created the Mexican American Culture Center, which was established in 1999 at Mexican Heritage Plaza. MASC transformed into the Students for the Advancement of Mexican Americans (SAMA). This same year, a student strike at San Francisco State College was organized by the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), demanding the creation of a Department of Raza Studies under the School of Ethnic Studies as well as open admission to all students of color. This event, which had led to violent confrontations between students and police, prompted Mexican Americans and other third world student activists to form a rainbow coalition in which many San José State University (SJSU) and Santa Clara University Chicano students participated. These protests led to the establishment of the Chicano Studies Program at SJSU, the oldest Graduate Program in Chicana/o Studies in the country, and catalyzed a push for a separate Chicano Commencement. Among the groups pressing for change at SJSU were the Chicano Vietnam War veterans who were activated by the anti-Vietnam War Movement and returning to school on the GI Bill. Students like Victor Garza, now Dean at Evergreen Valley College, and Ramon Martinez, retired teacher, principal, and administrator in San José Unified School District, reached out to local high schools to encourage students to attend college, and to come to SJSU. In the 1960s, Chicano student activists organized on college campuses throughout Santa Clara County, California, and across the nation. SJSU students Luís Váldez, a scholarship recipient in math and physics, and Roberto Rubalcava j oined the Marxist Progressive Labor Party (PLP) and traveled to Cuba in 1964 as part of a PLP delegation. While many of their contemporaries embraced the more conservative political approach of accommodation and assimilation in American society held by the previous generation, Váldez and Rubalcava took a more radicalized approach to politics. Together they produced the first Mexican American radical manifesto, “Venceremos!: Mexican American Statement on Travel to Cuba,” diverging from older Mexican American middle class civil rights organizations’ assimilationist policies. Váldez changed his major to Theater and joined the anti-establishment radical theater group the San Francisco Mime Troupe upon graduation, where he would continue his critique of assimilation tactics. In 1965, Váldez participated in César Chávez’s farm worker organizing efforts in Delano, and wrote the Plan de Delano, which promoted the principle of organizing for social justice. That same year, Váldez founded the Teatro Campesino, recruiting its members from among Chicano student activists in northern California. Dr. Carlos Muñoz, founding chair of the first Chicano Studies Department in the nation in 1968 at the California State University at Los Angeles and founding chair of the National Association of Chicana & Chicano Studies (NACCS), credits Luís Váldez and the cultural work of the Teatro Campesino for many of the concepts of Chicano identity and the emergence of the Generación Chicana.

-

San José Local Groups Fight Discrimination in K-12 EducationFor Mexicans, the path from public school to college was fraught with many obstacles. Before WWII, most ethnic Mexicans attended public school only up to the 8th grade. After WWII, ethnic Mexican students attended public high school, and some even enrolled in college. Public education for immigrant groups typically emphasized Americanization, prioritizing English skills and useful trades. Although segregated schools were no longer legal in California after the 1947 Mendez v. Westminster case, schools in Mexican neighborhoods were often older facilities with fewer resources, and few had Spanish-speaking teachers. Ethnic Mexican high school students were not tracked to college. Frances Palacios, who attended San José public schools, described a meeting with her high school counselor: “I told him what I wanted to take. When I did, he told me I didn't have the brains for it and would probably fall through, and to continue taking typing and filing. So, I did. I didn't take any college prep courses, because he felt I was incapable” (Frances Palacios, Chicano Oral History College, Special Collections, SJSU Library). Palacios eventually earned a BA and an MA in order to become a high school counselor who would help ethnic Mexican students go to college. Local ethnic Mexican parents became increasingly concerned about the poor quality of education that their children received. At Roosevelt Junior High School in San José, parents found that the police assigned to the school harassed ethnic Mexican students, and these children received discriminatory treatment from both teachers and other students. The parents pressured the school district and succeeded in replacing 36 teachers, a principal, and a vice principal. Despite the new faculty, the parents were still fighting structural inequality in the school system. Similar to other ethnic Mexican high school students throughout the U.S. in the 1960s, and in particular in 1967 Los Angeles (the first such action in California), students at Roosevelt Junior High School organized a “Blow Out” (or walkout) to resolve the educational inequalities. The Chicano Movement established an empowering political and cultural identity that was both Mexican and American. Chicano students of all ages in Santa Clara County might be involved concurrently in local community organizations like United People Arriba (UPA – United People Upward) and the Brown Berets (BB), and in student-led groups like the Student Initiative (SI), the Mexican American Student Confederation (MASC), Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO), and the United Mexican American Students (UMAS). Meeting with other Chicano student groups and other students of color, they found common ground with young activists throughout California and across the nation. A chapter of MAYO was started at San José High School with the help of organizer Lino Lopez in 1968. At that time Lopez worked with Mexican American youth and local schools in Santa Clara County to create bilingual programs. MAYO, founded in 1967 in San Antonio, Texas, stressed Chicano cultural nationalism and direct political confrontation, using mass demonstrations involving both university students and teenagers to accomplish its goals.

-

Cherries to (Silicon) Chips: Local Urbanization, Redevelopment and Displacement Contributed to Local Chicano AdvocacyIn 1960, ethnic Mexicans made up 20% of the population of the City of San José. The largest concentration of ethnic Mexicans in Santa Clara County resided in the unincorporated area of San Jose’s developing Eastside. Downtown San José, adjacent to the historic downtown Mexican colonia, became the hub of a vibrant regional business and entertainment district that drew Spanish-speaking clients residing in the Eastside colonia, worker neighborhoods in surrounding towns, and smaller unincorporated communities of Santa Clara County. Between 1960 and 1970 the population of Santa Clara County grew by 66%, with Spanish-surnamed residents growing from 12% to 18%. As the most-populated municipality in the County, housing the largest number of ethnic Mexicans, San José continued to serve as the center for social, cultural, and political activity for ethnic Mexicans in the South Bay. Unlike other urban areas, where “white flight” resulted in a declining urban core, the ethnic Mexican population settled in these areas, starting businesses and raising families. Annexation of the Eastside into the City of San José did not immediately bring needed improvements in streets, water or sewage systems. This was because San José had long relied on municipal bonds for civic improvements rather than raising taxes, which gave the growing city only sporadic access to funds. San José had grown exponentially, from 17 square miles in 1920 to 120 in 1970, sprawling toward nearby towns such as Cupertino and Sunnyvale. Annexation of adjacent communities soon converted orchards, farms, and canning and packing operations to technology/industrial parks and housing tracts. These growing communities now prioritized access to public services and infrastructure improvements. The 1958 the “Master Plan of the City of San José” fell in line with the goals of President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s anti-poverty programs of the 1960s. The federal Model Cities Program identified the central business district as crucial to the City’s growth and economy and one of its chief objectives for the City’s central core included an urban renewal program. The aim of the Model Cities Plan for urban renewal was to prevent existing blight from spreading, rehabilitate areas that could be restored, and to clear and rebuild those that were not “worth” saving (worth being a subjective term). The Redevelopment Agency’s first major urban renewal project in San José during 1967 was Park Center Plaza. Thirteen blocks encompassing nearly all of the west-of-Market neighborhood next to the center of downtown would eventually displace 466 mostly ethnic Mexican residents and 136 businesses. In 1968, San José applied for additional monies through the Model Cities Program. In 1970 four assembly districts that received federal Model Cities Program funding were in the predominantly ethnic Mexican neighborhoods of Mayfair, Tropicana, Olinder, and Gardner. Existing worker housing near fruit processing plants and canneries downtown and in the Eastside were identified to be cleared as part of the Plan. These ethnic Mexican neighborhoods also stood in the way of freeway expansion for Highways 280 and 680. The resulting demolition of blocks of existing residences and small businesses caused the displacement of local residents and the further fragmentation of older ethnic Mexican neighborhoods. Local residents questioned the definition of “blighted” and whether one of the criteria were the higher numbers of people who spoke little or no English. Homes and businesses in this area were often sold for less than fair market value, so options for purchasing other property were extremely limited. In response, the younger generation of Chicano organizers expected more action from their local government now that ethnic Mexicans also served on municipal councils and commissions. They were skeptical of large federal programs such as the Model Cities Programs and lobbied and mobilized in the streets to address issues such as discrimination in housing, institutional racism, police brutality, healthcare access, and labor rights. New organizations like the Brown Berets, United People Arriba (UPA), and the Community Alert Patrol (CAP) reflected efforts by these younger Chicano groups to focus directly on these issues on a local level. Despite legal challenges to the Model Cities Program, redevelopment plans were generally supported by city residents who believed that they were necessary in order to create a stable local economy and safer neighborhoods.

-

Decline of the Canneries and Impact on Local Ethnic Mexican Population Led to Local Chicano AdvocacyWith the rise of Silicon Valley in the 1960s, Valley canneries were in decline due to the postwar transition from an agricultural to a technological/industrial economy. Technology was a booming field which attracted both local residents and new immigrants to the Valley, also contributing to a housing shortage. Agricultural employment declined as farmers sold entire orchards for real estate and industrial development. Consequently, many local canneries closed during this period. Though Mexican workers found local employment in urban construction and suburban domestic work, they were not as successful on the assembly lines of Silicon Valley’s emerging tech industry. In 1967, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act required that jobs not be gendered into “male” or “female” work. Title VII afforded more opportunities for women to work in warehousing and shipping, occupations traditionally reserved for men. Although cannery women’s benefits were lower than men’s,, in the 1970s and 1980s cannery work offered women stability, enabling many women to become homeowners and create worker neighborhoods, according to sociologist Patricia Zavella. Historian Glenna Matthews notes that this changed when the Teamsters took cannery representation away from the American Federation of Labor (AFL). In the 1970s and 1980s César Chávez’s new organization, the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA), created a legal project called “The Cannery Workers Committee” (CWC) to protest Teamster discriminatory treatment. Using the Civil Rights Act Title VII, the CWC won a number of cases that enabled ethnic Mexican cannery women to move from seasonal line work to higher paying, permanent warehouse-related cannery jobs. By 1976, most cannery jobs were unionized, providing ethnic Mexican women with wage, medical, holiday and retirement benefits. Technology workers were not as fortunate, holding jobs that were not unionized, providing none of the benefits. By 1987, there were only eight canneries left in the Santa Clara County, and by 1999 Del Monte had closed Plant #3, the world’s largest cannery operation. The demise of the canneries took access to well-paid union jobs with their opportunities for advancement away from ethnic Mexican workers.

-

Local Chapters of National Advocacy Groups: United Farm Workers (UFW)Farm workers had been specifically excluded from the protection of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 because Southern Congressmen did not want to enable labor organizing among Southern Black agricultural and domestic workers. American farm workers were not guaranteed the right to organize and had no guaranteed minimum wage. Without federal protection, state laws that applied to farm workers were largely ignored. In Santa Clara County, as in many parts of California, the majority of agricultural laborers were people of color living at the poverty level, often Spanish speaking with limited English skills, whose children might also be employed. Agricultural work was seasonal, so migrant laborers followed the harvests from one region to another, making them a difficult group to organize. Another major obstacle was the Bracero Program, Public Law 78, started during WWII as a temporary agreement between the United States and Mexico to recruit workers to relieve a labor shortage. The program continued until 1973 with the encouragement of local growers. Legally, no bracero could replace a domestic worker, though this provision was rarely enforced. Bracero workers could be used as strikebreakers and could be paid less, which depressed farm workers’ wages in general. In the decades immediately prior to the creation of the United Farm Workers Association (UFWA), two organizations had tried to organize farm workers in California. The Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee had been formed in 1959 by the AFL-CIO based on the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which Dolores Huerta helped to found in 1960 while continuing to work with the CSO in Stockton. AWOC was largely composed of Filipinos, Chicanos, Anglos. and Black workers, and led by experienced Filipino field organizer Larry Itliong. The National Farm Workers of America (NFWA) had been started by former Community Service Organization (CSO) organizers César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and Gilbert Padilla in 1962. Beginning as an organizer in San José in 1952, Chávez, who had grown up as a farm worker, had risen through the ranks to become national director of the CSO. Although the CSO worked with local communities to identify and resolve urban problems, it was not interested in organizing farm workers, so Chávez, Huerta, and Padilla left in 1962 to found the NFWA. At the end of the summer in 1965, farm workers with the AWOC demanded $1.25 per hour to pick the grape crop. When growers refused, on September 8, workers at nine farms went on strike. Growers then brought in strikebreakers, and the AWOC asked the NFWA to join the strike. On September 16, the NFWA voted unanimously to strike, and asked the public not to buy grapes without a union label. NFWA and AWOC merged to become the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, AFL-CIO (UFWOC) and the grape boycott became one of their first joint efforts. Born in Delano, Luís Váldez had returned to help the farm worker movement in 1965 after graduating from SJSU. That year, he created El Teatro Campesino (The Farmworkers Theater). The following year, Váldez, Dolores Huerta, and César Chávez drafted the El Plan de Delano, which framed the farm labor movement as a nonviolent revolution for social justice. UFWOC, as Chávez had envisioned, had become both a union and a civil rights movement. In 1975, renamed the United Farm Workers (UFW), they won the passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, a landmark agreement recognizing the right of farm workers in California to organize. In the face of continued opposition from the government and agribusiness, farm workers and Chicano student activists organized one of the largest labor rights campaigns in U.S. Farm Labor history, which was a significant milestone for the Chicano Movement. The Civil Rights Movement had, in more than two centuries of struggle, increased public awareness of the effects of racism against people of color, such as lower standards of living and discrimination in housing, employment, schools, voting, and everyday life. While the Civil Rights Movement had focused on the treatment of Blacks in America, the struggle for farm labor rights in California showed that this was also a struggle for civil rights. Because of César Chávez’s connection to Santa Clara County during the 1950s through his residency and his work with the Community Service Organization, Chávez maintained close ties during his UFW years. He often worked with Guadalupe Church, the CSO, and his sister Rita Chávez Medina during his UFW campaigns.

-

Local Chapters of National Chicano Advocacy Groups: The San José Chapter of La Confederación de La Raza UnidaLa Confederación de La Raza Unida [Confederation of the United Latino People] (CRU), founded in 1969, was a coalition of 67 nationwide Chicano organizations that succeeded in pressing government officials on redevelopment and gentrification issues during the 1970s. The establishment of CRU was a direct result of a violent confrontation between police and protestors at the Fiesta de Las Rosas (FDLR) celebration in San José on June 1, 1969. The FDLR was a floral parade during the late 1920s that celebrated the city and county’s mythical Spanish heritage with floats and people in costume. The event had not been held since 1933 due to the Great Depression, and the idea was revived in 1966 as an event that would help revitalize a declining downtown San José. While some members of the ethnic Mexican community supported the event, others asked them to boycott the event, explaining that it ignored the fact that many ethnic Mexican neighborhoods still lacked adequate housing or public services. An estimated 75,000 people attended the event, including 100 protestors, representing some 35 San Francisco Bay Area Chicano organizations. Police charged the protestors as they assembled to join the parade, claiming that the protestors attacked, forcing the police to use riot tactics. As portrayed in the media, the confrontation reinforced stereotypes of ethnic Mexicans as criminals and trouble makers. After their encounter with the police, the protestors gathered at Guadalupe Church on the Eastside to discuss the event and decided that a coalition group was needed to deal with the interrelated issues they faced. Within a year the CRU had opened an office in downtown San José, representing a majority of organizations in Santa Clara County working with the Spanish-speaking community. By 1971 the CRU represented over 200,000 ethnic Mexicans in Santa Clara County, with members from various political, civic, religious, and educational backgrounds.

-

National Chicano Advocacy Groups: The Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) and the La Raza Unida Party (LRUP), 1970sLa Raza Unida Party (LRUP) created the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) in Crystal City, Texas, as part of Plan de Aztlán. MAYO had been started by five students at St. Mary's University in Austin, Texas in 1967 (see Section 6.12 on Advocacy in K-12 schools for the MAYO chapter in Santa Clara County). Inspired by the Black Civil Rights Movement and by leaders Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, LRUP was a Mexican American third party movement that supported candidates for elective office in Texas, California, and eventually in other areas of the Southwest and Midwest. Ernesto Galarza, then teaching in Santa Clara County, was elected Chairman of the La Raza Unida Party Conference at an organizational meeting in 1967. La Raza Unida began as a loose confederation of Latino/Mexican American civic, social, and cultural groups whose representatives were in El Paso to attend hearings of the U.S. Cabinet Committee on Mexican American Affairs. By their second conference in San Antonio in January 1968, chapters were being organized throughout the United States. While LRUP achieved some local success in elective offices in Texas, its greatest accomplishment was to inspire greater participation in the electoral process and advocate for the interests of the Latino community.

-

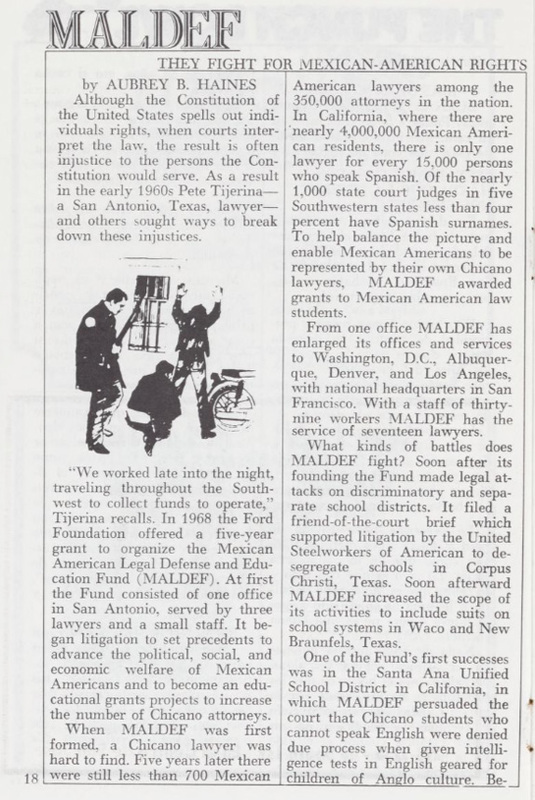

National Chicano Advocacy Groups: MALDEF, SCLR and SVREPMexican American Legal Defence and Education Fund (MALDEF) The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) was established in 1968 to battle voter suppression tactics, using the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as a model. In 1970, MALDEF successfully challenged a Texas legislative initiative that had created “mega districts,” which the U.S. Supreme Court later ruled unconstitutional for inhibiting minority voter participation. This ruling led to the Voting Rights Act of 1975. Southwest Council of La Raza (SCLR) The Southwest Council of La Raza (SCLR) was founded in 1968 in Phoenix, Arizona, by Herman Gallegos, Dr. Julian Samora, and Dr. Ernesto Galarza with the goal of reducing poverty and discrimination, and to improve life opportunities for Latino Americans. Their initial efforts were focused on the Southwestern states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Colorado. In 1972 they opened a national headquarters in Washington, D.C. with a new name, the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), which reflected their expansion into communities across the United States. These actions supported advocacy, developed resources, and helped strengthen Hispanic community-based organizations. Southwest Voter Registration Education Project (SVREP) One of the most successful advocacy groups was founded in 1974 by William C. Velásquez. The goal of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project (SVREP) was to mobilize and empower the Latino community by facilitating voter registration drives and initiating legal challenges. By 1988 a total of 75 lawsuits had been filed to help undo gerrymandering and eliminate language barriers and other voter suppression practices.

-

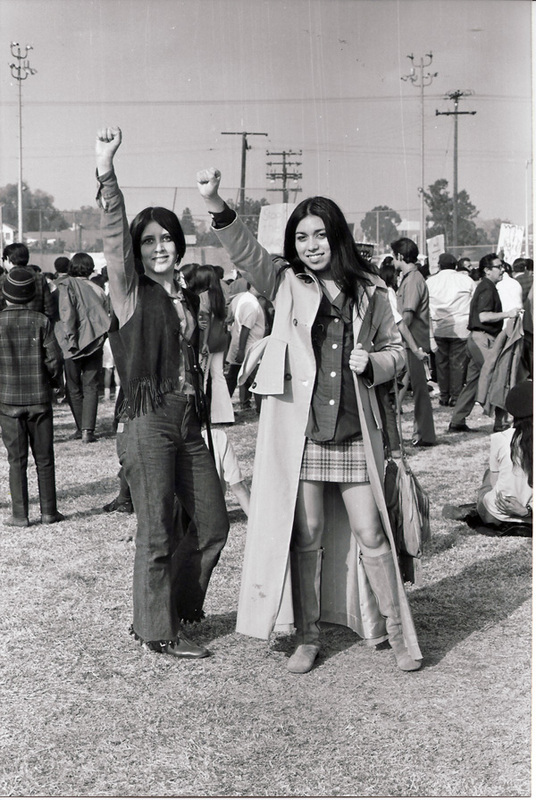

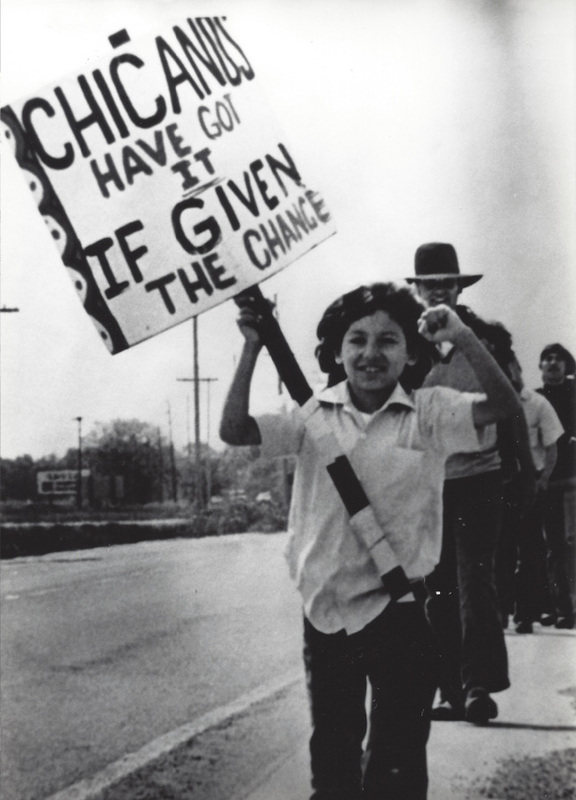

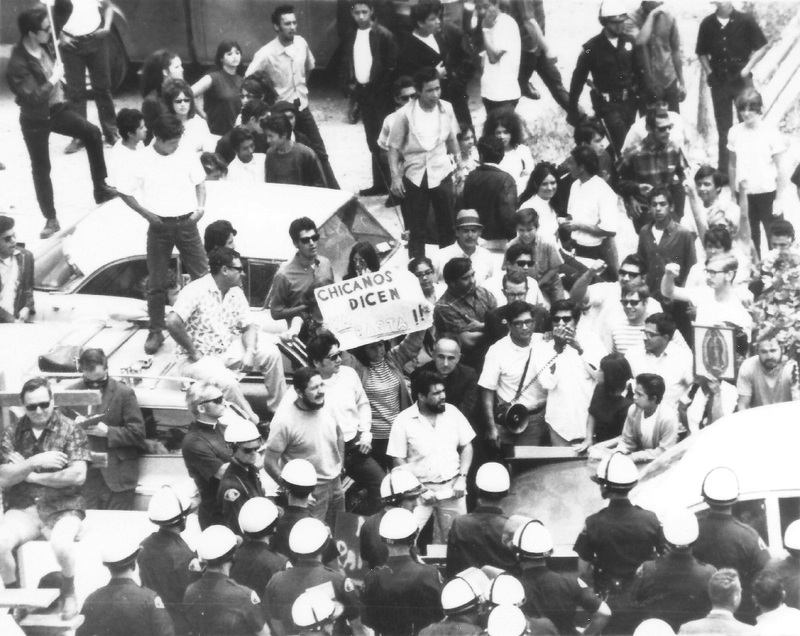

Chicano Anti-War Movement Action: The Chicano MoratoriumThe Chicano Moratorium march was held in Los Angeles on August 29, 1970, with more than 20,000 Mexican Americans of all ages marching through East Los Angeles to protest the Vietnam War and the effects of the disproportionate draft and heavy casualties among Mexican American youth. The National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against The Vietnam War was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that built a broad-based coalition of Mexican American groups to oppose the Vietnam War. At the height of the war, around 10 percent of U.S. residents were Latino/Mexican American but they made up about 20 percent off all U.S. troops killed in Vietnam. With fewer Latinos/Mexican Americans eligible for draft deferments due to their lower rate of college enrollment, opposition to the draft grew. The Moratorium march is widely considered one of the largest and most significant political demonstrations in Mexican American history. On that day, as protesters gathered for a rally at Laguna Park, Los Angeles County sheriff's deputies used the pretext of a theft nearby to brutally break up the gathering, resulting in three deaths. Among the dead was Ruben Salazar, a Los Angeles Times columnist who was hit in the head by a tear gas canister launched by police while he was seated in a bar after the march. The violence demonstrated by police at the march increased distrust and hostility of the community toward law enforcement and increased support for The Chicano Movement.

-

The Ideology and Goals of The Chicano Civil Rights Movement, 1968-1969Chicano cultural nationalism was clearly expressed in the 1968 El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, written by the Denver, Colorado based Crusade for Justice, an ethnic Mexican civil rights and educational organization founded by Corky Gonzalez. Gonzalez was the author of the 1967 poem I am Joaquin, which expressed a critique of racism that requires assimilation and the denial of one’s roots. It states: …that social, economic, cultural, and political independence is the only road to total liberation from oppression, exploitation, and racism. Our struggle then must be for the control of our barrios, campos, pueblos, lands, our economy, our culture, and our political life The Plan promoted cultural nationalism, pride in Mexican culture, and the creation of independent Chicano political and economic institutions, with community control of schools, advocating for self-defense, and supporting militant protest. The following year, El Plan de Santa Barbara, A Chicano Plan for Higher Education was written by the Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education, a group of students at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The 155-page document was created as a blueprint for the development of Chicana/o Studies programs in colleges and universities in the United States. It would also become the foundation for the Chicano student group Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). In 1969, students from twelve universities met at a conference in Santa Barbara, calling for the unification of all student and youth organizations into one organization to be called the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA). This included the United Mexican American Students (UMAS), the Mexican American Student Conference (MASC), and the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO). These groups represented student chapters from middle schools through the university level. Both El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán and El Plan de Santa Barbara were later criticized for excluding women and the LGBT community, reflecting the biases of that time. For this reason, the goals of the Plan for achieving inclusivity are viewed as a work in progress, continually modified by generations of Chicanx scholars.

-

The Chicano Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and 1970sDuring the 1930s and 1940s the African American and Mexican American Civil Rights Movements had worked closely together on legal strategies. Several decades later the African American Civil Rights Movements fight for equality in the South during the 1950s and 1960s inspired the Chicano Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and 1970s. While The Chicano Civil Rights Movement worked on many societal injustices, it focused on key issues of land ownership, rural and urban workers' rights, artistic expression, and educational and political equality. The Chicano Movement sought to combat institutional racism, promote cultural autonomy, and work to guarantee equal labor and political rights. This movement would spark a national conversation about the political and social autonomy of Mexican American/Latino groups everywhere in the United States. The term Hispanic was popularized in the 1970s as a bureaucratic convenience to categorize all Spanish-speaking people in the United States. This term ignores the fact that there are many different cultural groups within the “Hispanic” label, each with their own history and experiences. Though the impact of the Chicano Movement was felt across the country, each region could have a different focus because of historical and cultural variations. In the Southwest, particularly in Texas, New Mexico and Colorado, the majority of Spanish-speaking communities identified with a Spanish colonial past, rather than a Mexican immigrant history. California, even with its origins as a Spanish and Mexican territory, was relatively isolated from the center of Mexican culture and government due to its geographically inaccessible deserts and mountains. During the California Gold Rush, the small population of Spanish New World colonists and their descendants were overwhelmed by immigrants from every nation, along with the Americans who soon dominated the state’s power structure and economy. It was not until after the Mexican Revolution, World War II’s Bracero Program, and the post-War period that California saw large numbers of newly documented and undocumented immigrants residing in the state. As a result, the Chicano Movement in California, established by the children and grandchildren of these pre-1960s Mexican immigrants, forged a new identity and increased their political influence by the use of the new, more confrontational tactics of the 1960s and 1970s. In the Santa Clara Valley, the original group of Spanish-speaking settlers has been continually renewed and enlarged over the last 150 years by immigrants from Mexico and Latin America and migrants from throughout the Southwest. The largest group of Spanish-speaking immigrants has historically come from Mexico.

-

The Rise of Chicano Politics in the 1960s and 1970sU.S policy long encouraged immigrant assimilation, with new citizens expected to acquire English as their language and culture in order to become “American.” In the United States, the term “Mexican” is a large category that encompasses American-born people of Mexican descent, immigrants from Mexico who have become naturalized citizens and Mexican nationals who reside in the United States but are not American citizens. While some immigrants chose not to become citizens, reasoning that it might not make a difference in how they were treated, some ethnic Mexican organizations supported naturalization. The first Mexican American organizations, during the pre-1960s period, advocated for citizenship and assimilation. During the 1960s and 1970s, a number of Mexican Americans questioned whether assimilation was possible or even desirable because of prevalent racism in the United States. Equity in education remained a major issue, an obstacle to better jobs and a better life. A new generation of ethnic Mexican college students uncovered their history and critically analyzed what they had been taught in public schools. At the same time, with the rise and successes of César Chávez, a sense of ethnic consciousness and unity grew around the farm labor movement. The Black Civil Rights Movement had also inspired many ethnic Mexicans to consider whether more direct strategies, moving from the courts to the streets, would be more effective in obtaining their legal rights under the U.S. Constitution. Although ethnic Mexicans suffered the same types of economic, social, and political discrimination that African Americans and other people of color endured, there are important differences. American policies on immigration and citizenship affected all Mexicans. American-born Mexicans who had been deported during the Depression were suspected of taking jobs that could be offered to citizens. Ethnic Mexican families made up of both citizens and undocumented immigrants faced the possibility of losing one or both parents to deportation. Mexican immigrants tended to live in neighborhoods with other native language speakers in order to survive with their limited English. Since bilingualism was not generally viewed as an asset, speaking Spanish could be an obstacle. Some Chicanos viewed themselves as a colonized people, based on their belief that the United States government had failed to live up to the promise of full citizenship under the 1848 treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which had ended the war between the United States and Mexico. Mexican Americans were not accepted as fully American, but neither were they truly Mexican. Their closest identity was with Aztlán, the legendary original homeland in the Aztec migration stories, identified as the area of the Southwest conquered during the Mexican American War. In this case, the terms Chicano and Chicana began to be viewed as a positive identity to express self-determination and political solidarity.

-

Pre-1960 National Mexican American Advocacy Groups Continue in the 1960s and 1970sLeague of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) The first nationally recognized ethnic Mexican advocacy group in the United States, LULAC incorporated naturalization and voter registration as key elements in their organizing. Established in 1929, LULAC leadership advocated for community rights and an end to discrimination suffered by Latin American citizens in the United States. LULAC is the oldest Hispanic civil rights organization in the U.S., with a large middle-class membership and focus on the rights of citizens, and is considered more conservative in their tactical approach. In the 1960s LULAC supported national and local candidates and mobilized Mexican American voters and candidates for political office. Community Service Organization (CSO) Founded in 1947 as a national organization to protect the civil rights of Mexican Americans and encourage political and civic engagement, the CSO was formed primarily by community organizers. Although it was a national organization, individual chapters played a critical role in developing local and state policies that impacted the labor and voting rights of Mexican Americans. The local San José CSO chapter (according to La Raza Historical Society of Santa Clara Valley) worked from 1955 to 1961 “to change statewide labor laws to enable Non-citizen Old Age Pensions in California.'' After César Chávez, Gilbert Padilla, and Dolores Huerta left the CSO in 1961 to form the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA), Lino Covarrubias and other San José leaders helped workers actually receive these benefits. During the 1960s and 1970s, three voting rights bills would prove critical to LULAC and CSO activities. The Voting Rights Acts of 1965 outlawed discriminatory voting practices adopted after the Civil War, including literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting. The Voting Rights Act Amendment of 1970 lowered the voting age in national elections to 18. This encouraged young people to engage in political activity. All of these bills would foster the creation of more politically focused advocacy groups. Finally, the Voting Rights Act of 1975 provided assistance for “language minority” citizens, offering bilingual ballots and voting instructions, and assistance for blind, disabled, or illiterate voters. American GI Forum The American GI Forum (AGIF) had been established after WWII by returning ethnic Mexican veterans who faced discrimination when attempting to join established groups, such the Veterans of Foreign Wars, with largely white membership. AGIF became strong advocates for Mexican American/Latino veterans with the slogan "Education is our freedom, and freedom should be everybody's business." In contrast to other Mexican American/Latino groups created prior to WWII, such as LULAC, the GI Forum took political positions in opposition to the American political establishment. The AGIF leadership campaigned against the Bracero program, supported legal challenges to school segregation, and marched in solidarity with Chicano protesters. Between 1969 and 1979, the AGIF led a national boycott against the Adolph Coors Company, challenging the corporation's discriminatory employment practices. AGIF also sponsored Mexican cultural events and commemorations such as Cinco de Mayo and 16 de Septiembre in San José, the largest such events in California. The San José Chapter of the AGIF was established June 6, 1949, by ethnic Mexican veterans of WWII. In the 1950s, veterans from the Korean Conflict joined the chapter. According to the Santa Clara County La Raza Historical Society, this chapter focused on bringing in community members to serve as counselors at the Santa Clara County William James Boys Juvenile Detention Ranch. By the 1960s, the San José Chapter and the newly formed Santa Clara Chapter (1961), with the associated Ladies Auxiliaries of the AGIF, joined together to sponsor community activities such as parades, fiestas, dances, queen competitions, and fashion shows, to raise scholarship money for ethnic Mexican students. In addition they held an annual Black and White Ball fundraiser at the Cabana Hyatt House in Palo Alto, raising millions of dollars for their cause.

-

Life After the CSO: Some of the Founding Leaders of the San José ChapterAlicia Hernandez, who did not like being in the spotlight that can accompany a leadership role, moved to San Francisco to continue nursing. Leonard Ramierez became a probation officer and helped to open the James Ranch Juvenile facility in Morgan Hill (William F. James Boys Ranch). He became chair of the United Way of Santa Clara County, a founder of the Hispanic Development Corporation, and a member of the GI Forum. After leaving the CSO in the early 1960s, Fred Ross helped organize residents of Guadalupe, Arizona, primarily Mexican Americans and Yaqui Indians, to gain basic services such as paved roads and stop signs. He then taught organizing skills to students at Syracuse University working on a campaign, supported by federal “War on Poverty'' funds, to organize African American residents living in dilapidated public housing. The idea of paying organizers with government funds to stir up people to challenge government policies proved controversial, and the funding was eventually halted. Returning to California in 1966, Ross became the organizing director of the United Farm Workers Association. He assisted the UFW in a campaign over who would represent workers at DiGiorgio, a major grower in the San Joaquin Valley. He would spend the late 1960s and 70s assisting Chávez and the UFW with various elections and boycotts, training thousands of UFW volunteers in his organizing methods. Well into the 1980s, he trained a number of groups working on a broad range of issues, from U.S. intervention in Central America to nuclear disarmament. One of his favorite axioms described the role of the organizer: “A good organizer is a social arsonist who goes around setting people on fire.” Recruited by Saul Alinsky to become a full-time organizer, Herman Gallegos decided to pursue his career in social work and received his Masters in Social Work (MSW) from U.C. Berkeley, becoming an advocate for Chicano youth and active in the local CSO. After graduation, Gallegos worked as a district director with the San Bernardino County Council of Community Services, a social planning demonstration project supported by the Rosenberg Foundation. In 1965, Gallegos, Dr. Ernesto Galarza, and Dr. Julian Samora were recruited by the Ford Foundation to serve as national affairs consultants. The group explored potential philanthropic support, making recommendations and identifying solutions to address the growing needs of Latino communities. Gallegos went on to become executive director of the National Council of La Raza in 1968, co-founder of Hispanics in Philanthropy, and a U.S. public delegate to the 49th General Assembly of the United Nations. César Chávez left the CSO because of its emphasis on urban social justice issues. In 1962 he and Dolores Huerta co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (later the United Farm Workers of America). Chávez believed it was important that the new union succeed through nonviolent tactics (boycotts, pickets, and strikes). Although Chávez’s methods as an organizer and labor leader were sometimes controversial, the movement he led brought farmworkers dignity and self-respect, as well as better wages and working conditions. In California, he pushed through what remains today the most pro-labor law in the country, the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, granting farm workers the right to organize and petition for union elections. As stated in the César Chávez Special Resource Study, issued by the National Park Service in 2012: “César Chávez is recognized for his achievements as the charismatic leader of the farm labor movement and the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), the first permanent agricultural labor union in the history of the United States. The most important Latino leader in the U.S. during the twentieth century, Chávez emerged as a civil rights leader among Latinos during the 1950s. Moreover, Chávez and the UFW sought to inspire all men and women to respect the dignity of labor, the importance of community, and the power of peaceful protest.“ The legacy of these organizers from an earlier time can be seen in the work of a generation of activists and community organizers who joined the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s and '70s, transforming their lives and inspiring the activism that continues through today.

-

CSO San José Chapter Organizing TacticsIn San José, CSO organizers held house meetings where they identified community concerns, which became the focus of their campaigns, and recruited potential members and volunteers. Formal meetings were then held at the Mayfair School to create an official organization. The main issues of concern to Eastside residents included improving essential services, paving streets, installing streetlights, dealing with police brutality, and addressing economic inequality. Due to the anti-communist fervor of the early 1950s, it was important to involve religious leaders like Fr. McDonnell to assure the authorities that CSO members were not Communists or political agitators, so the opportunity to hold regular meetings at the Chapel was welcomed. Articles in El Excentrico introduced more people to the organization and emphasized its roots in the local community. Juan Marcoida, CSO member and chapter president, hosted a radio program, CSO INFORME, for ten years on KLOK and KSJO radio stations, with businesses donating to cover airtime costs. CSO services were provided free of charge, and, with so many people in need of help, fundraising was continuous–donated Christmas trees and tamales were sold, musicians played for free at dances, and members held raffles and ran a secondhand store. Prior to World War II, only a small percentage of Mexican immigrants had filed naturalization papers since citizenship did not appear to improve their working or living conditions. CSO members learned that some problems required legislative remedies to develop better public policy, which made citizenship, and thus citizenship classes, more important. The CSO became part of a civil-rights coalition, including the NAACP, the Urban League, the Jewish Community Relations Committee, the Japanese American Citizens League, and other organizations that met regularly to frame the strategy for public policy involvement in California. By increasing their political power through citizenship classes and voter registration, these groups fought discrimination in education, housing, and employment on local and state levels. In the 1950s, the CSO San José Chapter lobbied to end citizenship requirements for Social Security benefits and promoted voter registration drives with the assistance of the G.I. Forum and worked with the NAACP to challenge discrimination of Mexicans against African Americans.

-

The Background, Recruitment and Rise of César Chávez to the CSOCésar Chávez was born in 1927, the second of six children in an extended family of devout Catholics, and grew up on his grandparents’ family farm near Yuma, Arizona. In 1939, during the Depression, the farm was auctioned and sold to cover back taxes. César’s father had been diagnosed with a lung disease requiring a move to a cooler climate, and the family joined the growing number of American migrant workers in California. Unlike sister Rita, who quit school at 12 years of age to work in the fields full time, Césario (César) carried family expectations as the eldest boy and was allowed to attend school while working in the fields weekends and holidays. Eventually, he and his family worked across California from Brawley to Oxnard, Atascadero, Gonzales, King City, Salinas, McFarland, Delano, Wasco, Selma, Kingsburg, and Mendota. The essential injustice and underlying racism the family experienced during those years made a strong impression on César. Despite the numerous interruptions to his education, he graduated from the eighth grade in June 1942 and became a full-time farm laborer until he joined the Navy in 1945. A Navy veteran by 1947, Chávez returned to working with the family as an agricultural laborer. He joined the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), picking cotton in Corcoran, near Delano. Cesar and his brother Richard both worked briefly in the lumber yards of Crescent City. However, the distance was too far from the rest of the family in San José, so by the 1950s, their sister Rita encouraged César and Richard to relocate their families to San José. Richard became a successful union carpenter, and César continued working in the fields and local lumber yards when, at 25 years of age, he met Fred Ross, Sr., in 1952. When Ross had begun to look for local organizers for the CSO, Alicia Hernández offered to introduce him to her friend Helen Chávez and her husband César, who had become active in social justice work through his association with Father McDonnell, pastor of the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel. Through Fr. McDonnell, Chávez had learned the principles of nonviolent resistance and been introduced to Catholic teachings that emphasized social justice and challenged economic and social inequalities. With Father Mac, Chávez had visited labor camps and farmworkers living beyond the Eastside. Fred Ross encouraged Chávez to become a full-time paid organizer for the Community Services Organization (CSO), and he soon began setting up chapters in the Bay Area and other towns across the state. Named executive director of the national CSO in 1959, Chávez moved to Los Angeles to work in the organization's main office. Though the CSO had become a successful advocate for communities of color, Chávez had not given up the idea of working with farmworkers and felt that the CSO was more focused on the problems of urban communities. In 1962 he left the CSO and moved to Delano, California, with his wife, their eight children, brother Richard Chávez, and Dolores Huerta, another CSO colleague from Stockton, in order to establish a union for farm laborers, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)